SOAS’ incognito academic inspires world’s most famous fictional archaeologist

Remembering a diplomatic spat caused by Japanese lecturer William McGovern

In 2015, few places in our world are inaccessible to the daring field academic or discerning traveller. Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet in the Himalayas, is one of the world’s highest and remotest cities; yet, if you charter a plane from London, it can be reached in approximately 17 hours.

The story in the early 1920s, however, was very different. Quite apart from the physical challenges, to enter Tibet’s ‘forbidden city’ required the express permission of the Tibetan Government. Famously secretive, this permission was rarely if ever bestowed on ‘outsiders’. In 1922, however, an American lecturer at SOAS (then known as the School of Oriental Studies, or School of Spies, depending on who you speak to/what you read) embarked on the trip despite not having secured the written permission to do so. The reverberations of that decision resulted in a UK newspaper scandal and quite the diplomatic headache for the then Chair of the School’s Governing Body Sir J.P. Hewett. It also allegedly played a significant role in inspiring one of the most beloved and recognisable fictional film stars of all time, the intrepid adventurer Indiana Jones (‘Junior’, if you’re Sean Connery).

The real-life model arguably had the more interesting life. His name was Dr William Montgomery McGovern.

Dr McGovern was appointed as a lecturer in Japanese at the School of Oriental Studies (SOS) on 6 January 1919, one month before the School was set to celebrate its second year anniversary. At that point in its early history, the School specialised in the teaching of Eastern and Middle-Eastern languages (the 1920 Annual Report, in the academic staff section, shows teachers of Arabic, Malay, Sinhalese, Telugu, Pali, Marathi, and Persian to name a few).

McGovern’s appointment added to what was already a remarkably international faculty.

His Tibetan episode began in December 1921 when the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland approached the India Office for permission to send an Academic Mission to Lhasa, with McGovern identified as one of the leaders of the expedition. The mission’s benefactor was William Dederich, Esq, the same man who had part financed the famed Sir Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 Antarctic expedition. (McGovern would later dedicate his 1924 book to Mr Dederich.)

At that time, not a great deal was known about the city in the West. Furthermore, the physical location of Lhasa meant that it was logistically very difficult to reach whether you were a welcome visitor or not. Knowing that attaining permission to visit Lhasa would be difficult, perhaps impossible, the Mission set out its aims accordingly in order to maximise its chances. The Mission requested an audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in order to represent what was being done in the study of Buddhism in the Western world; to promote scientific knowledge of Tibet; and to obtain filmed footage of Tibet, notably the great cathedral at Lhasa.

The India Office cleared the Mission to travel to the Tibetan city of Gyantse where it was then ordered to await the final decision of the Tibetan Government on its application for admittance to the capital. (The Indian Government had secured the right to send certain selected peoples to the interior of Tibet, as a result of the Younghusband expedition, 1903-1904.)The Mission reached Gyantse in October of 1922 and was met a week later with a refusal from the Government of Tibet to continue on to Lhasa. No doubt disappointed with the decision, McGovern requested that just he and a colleague be allowed to travel on to Lhasa but this was met with the same refusal. He then requested permission to remain in Gyantse for a three month period in order to study Tibetan language and literature but was a third time refused, this time categorically -the communiqué received by the Government of India expressed the desire of the Government that Dr McGovern and his colleague be sent back to India. Seemingly resigned to a failed Mission, Dr McGovern complied.

Were the story to end here, it would have made for a rather uninspiring and ordinary account; certainly it would not have aroused the interest of the broadsheets back in the UK. However, it is on McGovern’s return to India where this story takes a remarkable and drastic U-turn. Undeterred by his comprehensive refusal of admission to Lhasa, McGovern took matters into his own hands; he adopted the disguise of a Tibetan coolie and paid Tibetan guides to take him over the final treks of the mountains (during winter no less) all the way to the fabled ‘forbidden city’. On the hazardous journey, the clandestine troupe was hit by a sudden snowstorm that almost proved fatal; and at another stage, McGovern came down with a bout of dysentery, again a potentially fatal condition to have in that harsh environment. Other obstacles detailed in his book include leeches and malaria spreading mosquitoes.

Against all the odds, McGovern did reach the city at some point in February 1923. On arrival he revealed his presence to Tibetan authorities (a move McGovern later describes as ‘foolish’) who provided him with dwellings and kept his presence secret from the city’s inhabitants. He was eventually discovered and a crowd of monks, angry at the deception, attacked the house he was staying in with rocks. Allegedly, McGovern adopted his disguise again and was able to sneak out the back door to join the crowds throwing stones at his house. The discovery of a Western man in Lhasa incensed the city and McGovern was expelled six weeks after his arrival at Lhasa. The research and newspaper articles he and others published on his return to the West indicate that he was not idle with his time there.

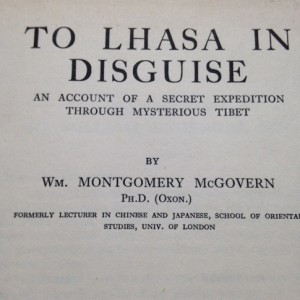

Upon his return to SOS in London, it was clear that the episode would not go overlooked. Between April and October 1923, much correspondence was shared between Sir J.P. Hewett, Chair of the School’s Governing Body, the India Office and Dr McGovern himself. In one lengthy letter, McGovern writes to Hewett with his version of events, stating he had committed no British legal or moral offence. He also suggested that all parties were “anxious to let the matter drop”. Hewett, in a follow up letter to Sir William Duke, Under Secretary of State for India at the India Office, inquired as to the ‘attitude of the India Office’ in regards to SOS’s retaining of McGovern as a member of staff. Despite the India Office’s reluctance to pursue the matter legally, Dr McGovern did eventually resign his post as lecturer at the School of Oriental Studies in a hand-written letter to the head of the department. In 1924, McGovern’s book To Lhasa in Disguise: A Secret Expedition through Mysterious Tibet was published.

McGovern went on to work for the Chicago Times as their Far East correspondent. He served as a Naval Officer in the Second World War, his Japanese language skills a major asset in the Pacific Theatre. After the war, he returned to academia: he taught at Harvard, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and gave lectures at around the USA at Army, Air and Naval War Colleges. Chicago’s Northwestern University would eventually become his academic home at the age of 33 when he was appointed a professor of Political Science, a position he would hold for the rest of his life. McGovern’s granddaughter is Academy Award nominated actor Elizabeth McGovern, perhaps best known for her most recent work as Cora, Countess of Grantham in the immensely popular TV series Downton Abbey.

The lengths that McGovern would undertake for the sake of his research (and the scintillating anecdotes that came with it) were no doubt the reason he never seemed to have trouble filling his lectures and seminars with eager young academics and students. Whether he was right to do the things he did is of course a matter for debate, but what is abundantly clear is that McGovern was a man that was passionate about the world, its many cultures and its many peoples. SOAS is very proud to have him as a member of our academic alumni.