Joseph Svoboda: Selling Clay Tablets in Nineteenth-Century Baghdad

by Nadia Ghanem

From the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, tens of thousands of archaeological artefacts from Iraq found their way into the collections of European and American museums. A substantial number of them did not come from publicly or privately funded excavations, but were bought by museums from antiquities dealers. Some dealers had turned this trade into a career, while others only sold artefacts occasionally. The first part of this series explored the activities of a professional: the antiquities dealer Ibrahim Elias Géjou who throughout his career, described himself as a ‘specialist purveyor’ of Assyrian, Babylonian, and Sumerian artefacts which he sourced directly from excavations that were ongoing during his lifetime. In this second part, the activities of Joseph Svoboda, an occasional trader of archaeological artefacts found in Iraq, will be explored in a series snapshots of Joseph’s life. Joseph was a steamship officer, born and raised in Baghdad, who witnessed how artefacts were traded and documented the transactions he observed in his personal diaries written between 1862 and 1908.

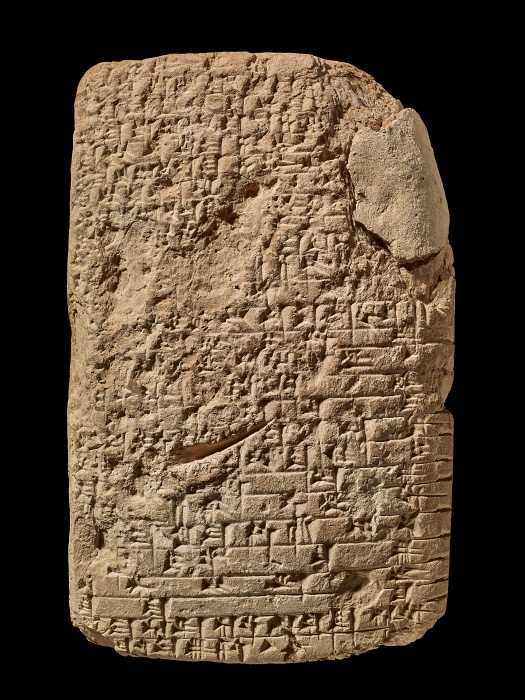

1896: BM 22740, the only clay tablet of its kind in a UK museum

Monday 11 May 1896

Svoboda Diary 42, p.25-26

At 1pm went up to Jeboory Asfar for some business, also gave him a box containing Tablets to be shipped to London to Mr. Budge in the British Museum

On 11 May 1896, Joseph Svoboda entrusted his good friend Jeboory Asfar with a case containing 117 clay tablets. They were to be shipped to Wallis Budge, keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum who was looking to purchase tablets for the BM from London. The parcel would be safely received a few weeks later, and the purchase of the lot was finalised in 1897. Joseph could not have known that among the tablets he sent, one was especially precious. Tablet BM 22740, as it came to be known, turned out to be inscribed with a list of ancient predictions (also called ‘omens’) written in the Old Babylonian language – a language used in Iraq between 2004 and 1595 BCE. The predictions are unusual: they are based on observing red spots on birds’ bodies. Diviners treated the red spots they observed as clues to decipher. From them the future of the individual(s) who had come for a reading could be told. Some of the omens of BM 22740 are clear enough, even today: they speak about the possibility of war, and the army’s military losses and gains as in this example: “if many red spots are present on the bird’s breast, on the right and left – my army and the enemy’s army who had confronted each other will not do battle” (BM 22740, reverse, lines 18-25). But other omens in this text link red spots to the ‘position’ (manzāz in the Akkadian language) of a number of gods and goddesses, statements that still puzzle scholars today, like this these two predictions for example: if left side has a red spot – position of Enlil (lines 9-10), If a red spot is set below the position of Enlil lower down – position of Ninlil (lines 11-13).

By the time BM 22740’s predictions were deciphered, translated and published by the French assyriologist Jean Nougayrol in 1967, 70 years after the tablet’s purchase, four other tablets similar to BM 22740 had emerged. Three had been bought by the Yale Babylonian Collection in 1913. One was donated in 1938 to the Museum of Arts and History in Geneva by the scholar who had originally purchased it, most probably from Ibrahim Elias Géjou. Like BM 22740, each of these four tablets was inscribed with predictions in the Old Babylonian language, made by reading red spots on birds’ bodies, but also their inner organs, a practice called ‘bird extispicy’. Today, scholars are aware that six more ‘bird extispicy’ tablets from the Old Babylonian period have surfaced. Four, dated to the end of the Old Babylonian period (c. 1700 to 1595 BCE), have recently appeared in the collection of the Hirayama Ikuo Silk Road Museum (HISM) in Japan. One of the four now in the HISM, as well as two others whose present location is unknown, were seen by the late professor Wilfred Lambert in a London auction house he did not name in the 1980s. Professor Lambert was one of the most renown assyriologists of his generation, also well-known for his regular visits to London auction houses to study clay tablets put up for sale there. These six tablets are said to come from the ancient city of Tigunānum whose precise location is unknown. The site from which they come was secretly and illegally excavated, and information on where it is located has not been shared. This ancient city-state is presumed to be located on the banks of the Tigris river, either in the extreme south of present-day Turkey or in the north of Iraqi Kurdistan. These tablets seem to come from the palace of Tunip-Teššub, ruler of the city circa 1630 BCE. It is possible that other ‘bird extispicy’ tablets are today in Iraq’s museum collections, but if so, they have not yet been reported. As far as we know today, only eleven tablets from the Old Babylonian period attest to the practice of predicting the future from birds’ bodies.

Clay tablets inscribed with lists of predictions written in the second and first millennium BCE have fascinated modern scholars, especially those who study prophecies, from the moment they were deciphered and translated. These texts not only attest to the practice of divination in Southwest Asia, they also document a type of vibrant intellectual enquiry founded on observing events with microscopic precision, and imagining infinite possibilities.

The study of predictions written in the second millennium has great limitations however because we do not know where most of them were excavated. Buyers and sellers did not share, or did not know, the find-spots of the artefacts exchanged. The eleven bird extispicy tablets for example were bought on the antiquities market but from which ancient building do they come from? Were they unearthed in a home, or a school? If in a palace, in which rooms were they found, and with which other artefacts? Answers can be conjectured, but none can be given on the basis of archaeological context.

Yet, beyond the text, BM 22740 has much to tell us about the many people it has met. Its story is not entirely lost, and to retrace the modern chapter of its eventful existence, we must rewind the clock to 1840.

Joseph Svoboda: steamship officer and diarist

Joseph Mathia Svoboda was born in 1840 in Baghdad, the city where he would make his entire life and where he passed away in 1908. His father, Anton Svoboda (1796-1878), born in Osijek, Croatia, had relocated to Baghdad from Vienna via Istanbul to trade glass and crystal. The year of Anton’s arrival in Baghdad is not known, but records show that on 12 February 1825, Anton married Euphemie Joseph Muradjian, a young local woman from an Assyrian Christian family. The couple had seven daughters, and four sons. Joseph did not follow in his father’s trade. On 12 February 1862, he became an officer on the steamships of the Lynch Brothers’ company, a post from which he retired in 1905. The ships ensured the transportation of passengers travelling from Baghdad to Basra on the Tigris river, and of cargo like wool, dates, wheat, ghee, and liquorice roots, as well as mail arriving from Bombay.

From his first day of work, Joseph began to write a personal diary. He was a polyglot who spoke Arabic, French, Italian, Turkish, and possibly Assyrian, and it is perhaps to maintain his English fluency that he wrote his diaries in this language, which he had learnt as a teenager. By the time he passed away, Joseph had written 61 diaries, which have all survived except for the first three. The physical copies are in the Iraqi National Museum and were digitized by the Ottoman Texts Archive Project. They are accessible on the University of Washington’s website.

A page in Joseph’s diary number 16, handwritten, dated to Friday 11 Feb 1876. Photo credit: University of Washington Digital Texts Project.

This double-decked steamship which ran on the Tigris river was part of the Lynch Brother’s fleet. Photo credit: Tinco Lyncklama – Adventurer and Socialite.

Impressively, Joseph’s diary entries all follow the same pattern, a testament to his methodical mind. Next to the date, Joseph would note the ship’s route, meteorological information, the arrival time at each port, types of cargo and the number of passengers with names that had caught his attention. Then came the events that had shaped his day. Among his most amusing records are those that recount his shooting trips hunting partridges, doves, and hares in the country, and his disputes with superiors when they would not allow him to bring aboard the wild boars he had hunted. Joseph naturally recounted many anecdotes about places and people over the years, and he also kept detailed notes of the archaeological artefacts he sold. These sales were occasional, Joseph was not a professional antiquities dealer, but he did partake in the trade at a time when numerous ancient sites were being simultaneously excavated in Iraq.

Large-scale excavations and exportations: the early years

Joseph Svoboda was seven years old when, on 1 May 1847, the Louvre Museum in Paris first exhibited the monumental statues in the shape of winged-bulls with a human face (protectors called lamassu in the Akkadian language) and palatial wall panels unearthed in the village of Khorsabad, 16 km northeast of Mosul, Iraq. Below Khorsabad’s ground rested Dur Sharru-kin, the ancient city and palace of Sargon II of Assyria (721-705 BCE).

Thorigny’s drawing shows five people moving though the Louvre’s Assyrian room. Monumental sculptures and wall panels are set against the walls. Unlike today, it is bare of any display cabinets and cases. Photo credit: Archéologie Culture online.

The artefacts had been found during excavations led between March 1843 and October 1844 by the French consul to the city of Mosul, Paul Emile Botta (1802-1870) and a team of 300 workmen from Mosul, which included many Assyrians who had just fled persecution further north. Botta had initially begun to excavate on the mound of Kuyunjik in December 1842, looking for ancient Nineveh, but had found little of interest, he felt. Three months later, he had moved to nearby Khorsabad, following the advice of a local resident, a cloth dyer who had brought Botta bricks bearing inscriptions in cuneiform. The people of Khorsabad had known about the presence of such inscriptions for some time, because they themselves had discovered many when building new homes.

By November 1845, the British explorer Austen Henry Layard (not yet Sir) was conducting his own excavations in the ancient city of Nimrud, financed by Sir Stratford Canning, British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. In December 1846, monumental wall panels and delicately carved ivory objects unearthed there were being sent to the British Museum.

Layard also excavated the mound of Kuyunjik, and found ancient palaces, much to the despair of Emile Botta who had been unsuccessful during his initial search. There, Layard and his team unearthed the Southwest palace of the Assyrian king Sennacherib and rooms bursting with inscribed clay tablets. When Layard left to pursue a diplomatic career in 1851, the British Museum appointed the young Iraqi archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam, who had seconded Layard since 1846. It was Rassam who, from 1852 to 1854, found the North palace of king Ashurbanipal, Sennacherib’s grandson, and its equally rich tablet-filled rooms which today make up what we known as ‘the library of Ashurbanipal’, held since its discovery in the British Museum.

Research institutions in the USA and Germany would also jump in the race to collect and appropriate, but did so later from 1889 (Nippur) and 1899 (Babylon) respectively. Meanwhile, excavations were also being conducted by Iraqis. Since 1869, the Ottoman Empire’s antiquities law had been clear: local people had the right to excavate their own land and to keep the objects they found. The Ottoman authorities’ antiquities laws became more careful and specific with time, but it still remained favourable to local landowners for some time. In 1874, the law stipulated that out of the finds a landowner had made one third had to go the authorities. Individuals could also sell artefacts if they wished – selling antiquities locally was legal until 1906. By the time Joseph reached adulthood, those around him, regardless of status or creed, were digging, exchanging, collecting, and selling tens of thousands of archaeological artefacts. The activity had not only become widely practiced and integrated within all social circles, it was also tremendously tempting given the fabulous profits to be made.

Archers holding bow and arrow are facing left. They are about to shoot their arrows at an enemy fort while other soldiers breach holes in the fort’s walls using iron bars. They are besieging a city. BM 124554 is in the British Museum (description here). Photo credit: British Museum online collection.

Portrait of Hormuzd Rassam by Philip Henry Delamotte, circa 1854

Rassam is seated and dressed in traditional cloak and headband.

Photo credit: creative commons.

1876: a coin collection for £67 (equivalent to £7,930 today)

6 Oct 1876

Diary 17, p.44.

I received lots of letters and papers from my father. He sends me Arabic papers and letters from Constantinople also from Blockey and sends me the letter of Mr Finis to read in which he says about the sale of my antiques and coins which I gave him last year but they went off very cheap and he is sorry for it. He sent me a printed catalogue of the coins etc. They were sold singly and all amounted to £ sterling 77.2.6 but deducting £9.13 for commission at 12 ½ per cent, remains a net proceeds of £67.9.6.

In a diary entry dated to 6 October 1876, Joseph writes he had been reading a disappointing letter from Mr Finnis, forwarded to him by his father Anton. At the time, Joseph was stuck on a steamship called ‘the Dejleh’ (the Tigris), which was slowly sinking despite the efforts of the crew to pump out the water for days. From London, Finnis was advising that Joseph’s collection of coins had been sold as agreed (Diary 15, p.168, 27 December 1895), but for less money than anticipated. Joseph had been hoping for at least £120 (equivalent to £14,203 today), and not only had the coins been sold for £77 and 2.6 shillings, but the agent had also taken a 12.5% commission, leaving him with ‘only’ £67 and 9.6 shillings. It would be a lesson learnt. By 1886, as we will see below, Joseph knew how to drive a hard bargain.

The face of the coin shows a side view of Athena’s helmeted head. The reverse shows the goddess Nike standing (click here for description). The coin was purchased by the BM from Mr Spiridion Mostra in 1852. Photo credit: British Museum collection online.

1877: marriage and family

The following year would have a lasting impact on Joseph’s life, and it would have nothing to do with collecting artefacts. On the evening of Thursday 11 October 1877, Joseph Svoboda married Eliza Marine, a widow. The marriage caused a violent rift between Joseph and his father Anton. Joseph’s family had hoped he would marry Eliza’s daughter, but when he chose Eliza instead, Anton warned he would never give his blessing. On the morning of the wedding, father and son came to blows and passers-by had to intervene. Anton had tried to stop Joseph from strangling his sharp-tongued older sister (also called Eliza) by hitting him with his walking stick. In retaliation, Joseph had thrown a narghile at her, and had run to his room to get his gun threatening to shoot all those who had gathered to insult his bride (a colourful episode recounted in his diary number 18, p.141-144). When Anton passed away almost a year later, on 7 September 1878, father and son were still estranged and Joseph’s all-engulfing sorrow at having missed the chance to reconcile still echoes in his accounts.

Despite the family feud, Joseph quickly settled in a new house with Eliza, and continued what he had always done: cruise from Baghdad to Basra on a steamship, and write his diaries. In 1881, he recorded a detailed account of his visit to an excavation site that would give him the opportunity to select archaeological artefacts from the very spot where they had been found.

1881: a day’s visit of the excavation at Abu Habbah, ancient Sippar

Monday 9 May 1881

Svoboda Diaries 23, p.88-89

Capt Cowley proposed to me to go out to Mahmoodyeh on Wednesday to see the excavation going on by Mr Hormuz Rassam of some Babylonian buildings discovered at some mounds called Tell Aboo Hebbeh. They have found some very interesting relics, all the bricks are inscribed with cuneiform.

Joseph visited the ongoing excavation of the ancient city of Sippar in 1881. The day trip had been Captain Cowley’s idea (Joseph’s superior on board ship). Cowley had heard that ancient buildings and cuneiform inscriptions had been found there. On the morning of 11 May 1881, having hired donkeys and horses to make the journey, the party left on guffa-boats to Mahmoudiyah. It would be a journey full of comical mishaps. Only Joseph had thought of bringing water for example, and after a detour caused by the overflowing river, the group had arrived utterly parched.

Wednesday 11 May 1881

Svoboda Diaries 23, p.91

We saw all the diggings going on by 42 Arabs attended by Abdulahad Thoma brother of Abdulkerim Thoma, a Mossully appointed there by Mr Hormuz Rassam. Some walls and corners are very large and most of them inscribed with Babylonian cuneyform some of 4.5 and 6 lines. We had our breakfast on the top of the mound and then descended to go to some Arabs of the Jenabeen or Elboo Segar encamped on the canal near a large tomb called Seyd Abdulla greatly venerated by the Arabs. It is something in shape like that of Hudeitha of Ctestiphon. We went inside of it and spent the day, had tea, sour milk and butter from the Arabs. We made up our mind to sleep on top of this house, and start early tomorrow to return back […] At 2 am we turned up, dressed, collected our kit, and had tea. At 4 ½ we started to come back, had to recross the Mahmoodyeh canal and take the same road as we came out.

It is during this trip that Joseph met Abdulahad Toma, the brother of Abdulkerim Toma, the assistants of Hormuzd Rassam, who was excavating there for the British Museum. The brothers, who were from Mosul, spent many years looking after excavations for Rassam, and became highly skilled. They also accumulated a large collection of artefacts for themselves over the years, which they sold on the antiquities market.

Joseph returned from Sippar with cylinder-seals: small barrels, no bigger than a thumb, made of semi-precious stones carved with illustrations, often accompanied with an inscription of the owner’s name. From the 4th millennium to 5th century BCE, cylinder-seals were part of everyday life in Southwest Asia. They would be rolled on wet clay to stamp an imprint that functioned like a signature. Holes in their centre indicate they would be hung on a string, carried around the neck presumably like a necklace, or tied in clothing. Because they are so light and small, cylinder-seals (like coins) were easily traded and were scattered across the world. Today, many can be viewed in national collections. The Met Museum’s online collection, for example, showcases over a thousand (a list can be browsed here). For each item, information on the stone type, period, and size is given, as well as provenance indicating who sold, donated, or excavated the object, and the date it entered the Met’s collection.

Joseph would sell his cylinder-seal collection in 1891 to the British Museum.

A green cylinder-seal is on the left. It is made of quartzite stone, dated to 2000-1900 BCE. Next to it on the right is the impression it makes when rolled. The image depicts several animals, human figures standing, and a deity sitting (click here for description). Photo credit: The Met Museum collection online.

1891: 25 cylinder-seals for £130 (equivalent to £16,943 today)

Wednesday 4 February 1891

Svoboda Diaries 35, p.159-160

Mr Budge of the British Museum called on me on board about the purchase of my Babylonian Collection for the cylinders, 25 of them which I have been collecting for the last 20 years, he offered me the 130 £ sterling which I had asked for before and will call on me on Friday to examine them.

Joseph Svoboda met Wallis Budge in person for the first time in 1888, when Budge was first sent to Iraq by the British Museum. As luck (or fate’s sense of mischief) would have it, Budge had boarded the very ship on which Joseph Svoboda worked as officer, heading to Baghdad from Basra. In a diary entry dated to Thursday 9 February 1888, Joseph records his meeting with this “English passenger” who was buying inscribed clay tablets (Svoboda Diary 31, p.73). Budge had been made aware that Joseph had a collection of cylinder-seals, and went to visit him after returning from Hilla (Babylon) and Abu Habbah (Sippar) with Joseph’s colleague Captain Holland (Diary 31, p.87, Monday 27 March).

Monday 27 March 1888

Svoboda Diary 31, p.87

In the evening Antone and Mr Budge called on me, I showed him my collection of Cylinders 25 of them. He admired them much and especially the large one and said that they have no Cylinder like it in the British Museum, I told him I was offered 2800 francs by Mr Dieulafoy 2 years ago but I wanted 3000, he said that when he goes back he will refer this to the trustees of the Museum for their purchase.

It was not the first time Joseph had been approached to sell this collection. He had been assembling it for 20 years. In April 1886, he had refused to sell the cylinder-seals to Marcel-Auguste and Jane Dieulafoy, the famous French couple who were then excavating the city of Susa in Iran for the Louvre Museum:

Monday 19 April 1886

Diary 28, p. 195-196 (1,500 francs are equivalent to €5,987 euros today)

Mons and Madame Dieulafoy came off to me to see and buy my cylinders. I have 25 of them, they came from Sheshter [Susa, Iran] by Mohamerah 10 days ago and brought the antiquities which they have excavated for the last 6 months and are to return back tomorrow up the Haroon to Shuster to bring down the rest and then ship them on board a French man of war. I asked 4000 francs for the 25 cylinders and 2 amulets. He offered me 1600. I refused, he then picked out the 6 largest and best ones and gave me 1200 Francs for them. I refused and asked 1500 for these so they went away.

Wallis Budge bought Joseph’s 25 cylinder-seals three years later in 1891, for £130 (Diary 35, Friday 6 February 1891, p.160-1). The British Museum online records show that in that year, Budge had returned to London with 31 cylinder-seals (which can be viewed online here). All are described as having come from Sippar.

Four years later, in 1895, Joseph would sell another collection of his to the British Museum, but this time it would be entirely made of inscribed clay cones and tablets. In 1896, Joseph was offering a new lot for sale, the one made of 116 clay tablets plus BM 22740 described above.

For full description click here. Photo credit: BM online collection.

Meeting and leaving Joseph

Joseph is wearing a three-piece suit, a tie, and holds a walking stick. He seems to be standing by a river or the sea. Photo credit: Svoboda Diaries Project.

By the time the British Museum bought Joseph’s 117 clay tablets in 1897, Joseph’s attention had been diverted elsewhere. In May that year, Joseph and his wife Eliza had left Baghdad for Paris to leave their son Alexander in the care of their friend Ibrahim Elias Gejou. Once his parents were gone, Alexander then 18 years-old, began to misbehave, spending large sums of money. He had also met Marie Josephine Derisbourg, a young French woman with whom he eloped, and married, to his parents’ utter astonishment. For the best part of 1897 and 1898, all Joseph could write about was attempting to stop the marriage. Probably too caught up in his distress, Joseph did not remark on the irony of fate, his own father having stood against his choice of a life partner, an attempt that also failed to stop the wedding. Joseph never did cut off ties with his son however, and chose to berate him (no doubt lovingly) for months instead.

Joseph Svoboda’s diaries are an invaluable source of information on how the trade of archaeological artefacts operated in Iraq in the nineteenth century. Such first-hand accounts are rare. The only extensive source of information to reconstruct this trade’s history is to be found in old correspondence between sellers and curators kept in museum archives today. From Joseph’s accounts, we see who was engaged in buying and selling artefacts, and what type of profits were being made. One aspect of the trade which is striking but not surprising, is that it mostly involved men. Women antiquities dealers are rarely encountered, yet we know of at least one exception: the antiquities dealer Mrs Ferida Shamas, a discreet figure who operated for years in a trade dominated by men and who happened to be one of Joseph’s friend.

To be continued…

References

Anor, Netanel and Cohen, Yoram. “Bird in the Sky – Babylonian Bird Omen Collections, Astral Observations and the manzāzu”, forthcoming.

Botta, Paul Emile. “Lettres de M. Botta à M.J. Mohl”, Journal Asiatique, vol 4, no.2, July-August 1843, pp.61-72.

Collon, Dominique. Near East Seals, British Museum, 1990.

Dieulafoy, Jane. A Suse, journal des fouilles, Hachette, 1888.Homan, Zenobia Sabrina. “Nuzi and Tigunānum”, Chapter 5, in Mittani Palaeography, Cuneiform Monographs, Vol. 48, Brill, 2019.

Layard, Austen Henry. Discoveries in the ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, 1853.

Nougayrol, Jean. “« Oiseau » ou Oiseau?”, in Revue d’Assyriologie and d’Archéologie Orientale, vol. 61, no.1, 1967, pp.23-38.

Place, Victor. Ninive et l’Assyrie, Imprimerie Impériale, 1867.

Parrot, André. Archéologie mésopotamienne, Albin Michel, 1946.

Porada, Edith. Why Cylinder Seals? Engraved Cylindrical Seal Stones of the Ancient Near East, Fourth to First Millennium B.C. The Art Bulletin , Dec., 1993, Vol. 75, No. 4, Dec. 1993, pp. 563-582

Maul, Stefan. The art of divination in the Ancient Near East, translated from the German by Brian McNeil and Alexander Johannes Edmonds, Baylor University Press, 2018.

Svoboda, Joseph. Diaries 3-61, from May 1865 to December 1908.

Links to archaeological artefacts in museum collections referred to in this blog article

BM 22740: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1897-0510-3Cylinder seals in the Met Museum, online collection: https://www.metmuseum.org/search-results#!/search?q=Cylinder%20seal

Thirty-one cylinder seals in the BM bought by Wallis Budge in 1891: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=budge%3B&keyword=1891&object=cylinder%20seal&view=grid&sort=object_name__asc&page=1

Inscribed clay tablets and cones sold by Joseph Svoboda to the British Museum in 1895: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=1895&agent=Yusuf%20Svoboda&view=grid&sort=object_name__asc&page=1

117 inscribed clay tablets sold by Joseph Svoboda to the British Museum in 1897: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search?keyword=1897&agent=J%20Svoboda&view=grid&sort=object_name__asc&page=1

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

she/her

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at SOAS’ School of History, Religions, and Philosophies. My current project is based on the study of clay tablets inscribed with predictions (omens) written in the Old Babylonian language, and dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 2004-1595 BCE). The aim of my research is to investigate the content of these ancient predictions, the desires and anguish they express before unpredictable tomorrows, as well as the provenance of these tablets, with a focus on how most of these ancient Iraqi artefacts were bought by museums in Europe and the US from antiquities dealers trading from Baghdad, between the late 1880s to the late 1920s.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London

One Comment

Comments are closed.