When Things Go Wrong: Smuggling Artefacts from Baghdad to London in the late 19th Century

by Nadia Ghanem

Many of the artefacts we see today in the ‘Ancient Near East’ collections of European and American museums were purchased in the late 19th and early 20th century from dealers who specialised in smuggling archaeological artefacts to Europe from Baghdad. In order to conduct their business with these institutions, such dealers would write letters to curators to propose collections, organise deliveries, negotiate prices, and agree sales. In so doing, they would pepper their correspondence with information about the manner in which their operations were conducted, as well as information about themselves as individuals, and what motivated them to specifically seek to enrich the collections of public and private institutions in Europe and America. Many of their letters still exist today in museum archives. The British Museum (BM) archive, for example, preserves hundreds of letters sent to the department of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities, written by dealers who exported artefacts to sell abroad in violation of the Ottoman antiquities law of 1884 (article 8). Although the correspondence volumes in the BM archive do not contain the replies of curators, these dealers’ letters alone are invaluable both to study how antiquities smuggling functioned post 1884, but also to reconstruct the life stories of the women and men who engaged in this trade. From the correspondence preserved by the BM, three types of sellers can be seen active between 1890 and 1900. The first are those who quickly turned the trade of archaeological artefacts into a long-lasting career, like the Iraqi-French antiquities dealer Ibrahim Elias Gejou, presented in the first part of this series. The second group had a profession unrelated to the antiquities trade, but occasionally sold artefacts to museum curators. The steamship officer Joseph Svoboda discussed in the second part of this blog series is a fitting example. But aside from the above two types, one group stands out conspicuously: antiquities dealers whose first sale to the department of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities went so disastrously wrong for them and who felt so cheated by low offers that they gave up trading with the BM altogether.

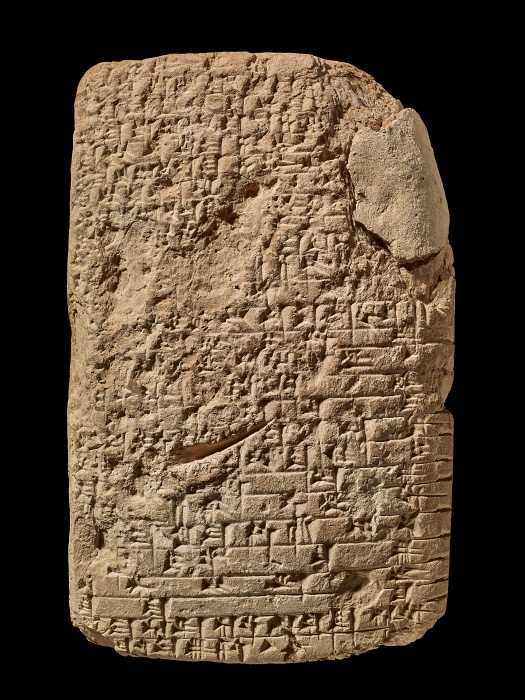

the king will have no rivals – written by Aham-arši, son of Lipit-Ištar, the diviner”. The decipherment and translation of this text were published in 1972 by the assyriologist Jean Nougayrol.

Based on the letters sent to the department between 1894 and 1900, this blogpost will recount the experiences of three sellers of this latter type. First, the story of 15 year-old Djemileh Hanna Sayegh, who sold her jewellery to invest in smuggling cuneiform tablets, will be reconstructed from her letters and those of her adoptive mother Ferida Antone Shamas. Next, the experiences of Eliza Kebaba, who unknowingly bought a collection of fake cuneiform tablets that made her investment worthless, will follow. This retelling will end with Rezooky Sayegh who, feeling cheated by the low price he was offered for the collection he sent, made no other attempt to sell to the department. This article is the third part of a series that aims to reconstruct the biographies of Iraq-based antiquities dealers active in the late nineteenth century from museum archives, and to reassemble from these documents the manner in which the smuggling of archaeological artefacts was conducted from Baghdad between 1890 and 1900.

When tablets arrive smashed: the case of 15 year-old Djemileh Hanna Sayegh

A groom and bride dressed in white and gold pose for a wedding portrait. Photo of the painting found on Pinterest

Djemileh Hanna Sayegh was 15 years old in 1897 when she contacted E.A. Wallis Budge, the Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities at the British Museum, to sell a collection of cuneiform tablets. She had been encouraged to sell artefacts to the BM by her adoptive mother, the antiquities dealer Ferida Antone Shamas, one of the rare women to have traded with the BM for as long as ten years, between 1894 and 1904. Ferida Shamas’ dealings with Wallis Budge were never smooth, but she seemed to have made enough of a profit in the first years of her business with him to encourage many of her family members to give this kind of enterprise a try. Her daughter Djemileh’s attempt however was marred by bad luck.

Djemileh’s first letter to the department dates to 28 January 1897. In it, she advises Wallis Budge that she had sent two cases of cuneiform tablets on a steamship called the SS Votigern, and that the department should expect a delivery soon. Her first letter represents what can be described as a standard approach. The majority of antiquities dealers in that period would directly send artefacts to the department of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities without first enquiring about interest or budget. They knew the artefacts would be bought. In December 1894, the antiquities dealer Joseph Svoboda put it plainly in his letter to Wallis Budge: “people have heard of the fine sale obtained lately at the Museum” (letter of 28 December 1894). The demand of foreign museums for archaeological artefacts from Iraq was so intense in that period that it was driving the price of artefacts (especially cuneiform tablets) found during ongoing excavations to an all time high. In 1895, Joseph Svoboda was even pleading with Wallis Budge to tell dealers that the BM was no longer interested in buying cuneiform tablets so that the price would fall to reasonable sums: “If you only give out that you require no more of these tablets, I am sure the price will go down here for they are all looking out to your demand for such articles” (letter of 26 June 1895). Joseph Svoboda could see that, increasingly, many individuals like him were being cut off from the trade. Artefacts were becoming so expensive that only the wealthiest of antiquities dealers could buy them. He also foresaw that even these dealers would soon loose out. The institutions to which artefacts were destined did not have the budget to buy artefacts at high prices, and dealers would simply be made to sell at a loss.

After shipping their artefacts, dealers would send what was then called a ‘bill of lading’, a document that enabled the holder to receive delivery of the items shipped. It would take three weeks to a month on average for steamships leaving the south of Iraq to arrive in the UK, and Djemileh Sayegh’s delivery should have been a straightforward affair. But something went badly wrong with her shipment. Not only was Djemileh told eighteen months later, on 9 July 1898, that her cases had been received by the department but she was also only then advised that the tablets had been damaged during transport. They had arrived in such badly broken condition that the Keeper, E.A. Wallis Budge, was not interested in buying them.

After enquiring about what had gone wrong from the steamship company, Djemileh learnt that the cases had been placed in the hold of the ship, contrary to what had been agreed. The tablets, she recounts, should have been put “under the protection of the captain”, because they had been declared as ‘specie’, that is, high value goods supposed to have been transported in a part of the ship less affected by pitching (letter of 18 August 1898). If Djemileh Sayegh had been told of the damage early, she could have claimed insurance, but she had been informed of the tablets’ condition so late that the delay for claiming compensation had passed. Djemileh had taken insurance on her collection as a matter of course. Among the antiquities dealers’ community, transport was known to have been precarious. For example, in March 1900, Ferida Shamas recounts that she had been notified by the steamship company Frank Strick & Co that some of her cases had been “lost at sea”. The manner in which the cases had gone overboard are not given in her letters, but she had to write to the department to organise her compensation claim (letter of 3 March 1900).

Djemileh Sayegh’s shipment continued to generate bad news for her. Not only did the purchase of the tablets not interest the curator on account of their condition, she was also now asked by the department to reimburse them the fees they had paid for storage. The tablets had apparently been left in the docks for some time, presumably because they had not been picked up on arrival. Unfortunately, the archive does not preserve the department’s answer to Djemileh, and the reason for these multiple delays is not known. As the owner and original sender, she was liable for this sum. Djemileh Sayegh wrote several letters imploring Wallis Budge to make her an offer regardless of the artefacts’ condition. From Baghdad, she was powerless. Like her mother Ferida Shamas, she had no contacts in London who could take the cases back on her behalf, or could try to sell them elsewhere. She also could not ship the artefacts back home, not only because of the cost, but because the Ottoman authorities would have confiscated the tablets. Djemileh was not the only dealer to have faced this dilemma. Henry Svoboda, the brother of Joseph Svoboda, also sold many Iraqi artefacts to the BM between 1894 and 1895. When told that the collection he had sent to the BM was of no interest, Henry had written that he could not take the artefacts back because they would be seized:

“You know that it will be very difficult for me to have them back here as the government will seaze [sic] them so I shall be much obliged if you take both those of D. Sassoon and the 10 cylinders you have and pay me what you think as I do not care much what you offer and they will always be of some use in your museum”

(letter of 27 December 1894)

Despite the authorities’ crackdown on the illegal exportation of antiquities, which included house searches as witnessed by Henry Svoboda who, like several dealers, regularly mentioned it (“the Turkish Government is confiscating every thing they find and even searching the houses of those that deal with them”, letter of 14th Sept 1894), smuggling was rife. In his letters, Joseph Svoboda recounts all these measures had little effect. Corruption also meant the seized artefacts would find their way on the antiquities market again anyway. His letter of December 1894 notes that:

“the Turkish authorities are trying to take possession of and confiscate all they can find, but not one fourth go to the government. The rest are sold by the officials secretly.”

(letter of 28 Dec 1894)

The situation in which Djemileh found herself was so desperate that she even asked that the tablets ‘be thrown in the sea’ if nothing could be done with them (18 August 1898). Her exasperation also led her to write exactly how she had got herself into this mess. She was planning her wedding, and to make a little nest egg in anticipation of her married life, she had decided to sell her jewellery to invest in selling cuneiform tablets to the British Museum. Many of her family members were doing this, including her mother Ferida, her uncle Joseph Antone Shamas and his wife Eliza Kebaba (discussed below). Djemileh had calculated that the tablets could fetch £65 (equivalent today to c. £8,872). But things had not turned out how she had imagined.

Separately from Djemileh Sayegh, Ferida Shamas also wrote several letters asking that a decent offer be made to her daughter. But matters worsened by September 1899. Wallis Budge was now threatening to start legal proceedings against Djemileh before the British Council in Baghdad. The charge is not specified in either of these women’s letters, but it was likely to do with recouping the delivery fees the department had paid. On 28 September 1899, Ferida Shamas wrote that:

I have been much disappointed to learn that you have been prepared to take legal proceedings against my daughter Djemileh before the British Consul in Bagdad on behalf of something which does not worth to be mentioned [sic] & which would never expect it from you but on the other hand I see that you were right somewhat on thinking that you do not know about Djemileh she is my daughter otherwise you would not have dealt with her in such manner.

After this long pleading letter, Wallis Budge dropped the threat and offered to pay £20 for the tablets (equivalent today to around £2,699). Although Ferida Shamas wrote back that she would have preferred £25, she agreed to convince her daughter to sell for this sum. Djemileh Hanna Sayegh’s last letter to Wallis Budge, dated 23 November 1899, formally accepts the money offered, but in it she stresses she only agreed to this to obey her mother. Payment for the purchase of Ms Sayegh’s collection was issued to Mrs Shamas, who confirmed it was received on 30 June 1900, three years after Djemileh’s first letter to the department.

Djemileh Sayegh’s letters contain many details about her personal situation, but it is in Ferida Shamas’ letters that one finds that Djemileh was 15 years old when she first approached the BM, and that Ferida was her adoptive mother. In her letter to Wallis Budge dated 20 December 1898, Ferida writes that Djemileh was barely 16 years of age in that year, and that she considered her as her daughter (“elle est encore jeune et ne dépasse guère sa seizième année; ensuite je la regarde comme ma propre fille”). Additional clues about the two women’s relationship can also be found in the diaries of Joseph Svoboda (digitized on the University of Washington, studied by The Svoboda Diaries Project). Joseph Svoboda was very good friends with several members of the Sayegh family in Baghdad. His wife had previously been married to a Sayegh. Joseph was also an intimate friend of Ferida Shamas, and in one of his diaries he recorded the name of her husband as one “Toma Hanna Sayegh” (Svoboda Diary no.41, p.1, 25 April 1895). Given this family name, it is likely that Djemileh was a close relative of Ferida’s husband. After this first sale, Djemileh Sayegh attempted no other with the British Museum. The manner in which Djemileh had been treated seems to have negatively impacted Ferida Shamas’ business relationship with Wallis Budge, which very much soured in that year. By 1903, they had entirely fallen out.

Embarrassing Forgeries: the case of Eliza Kebaba

Photo credit: the Royal Museums of Art and History

Eliza Kebaba contacted the department of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities in late May 1897 to offer a collection of 233 cuneiform tablets for sale. She had packed the lot in two cases, and had shipped them on a steamship called the SS Turkistan. Eliza must have been well acquainted with Djemileh Sayegh, because she was married to the brother of Ferida Shamas, the antiquities dealer Joseph Antone Shamas. Letters in the BM archive show that he too had begun to sell artefacts to the museum based on his sister Ferida’s recommendations. But he had more success than Djemileh and his wife.

Like Djemileh above, Eliza had to wait a while to receive a reply from Wallis Budge. She heard back from him 11 months later, on 20 April 1898, and the news was a shock to her: many of the cuneiform tablets she had sent were found to be forgeries. She was so aghast to learn that she had been fooled, and that she was only offered half of the sum she had hoped for, that it took her three months to reply – a delay about which she speaks in her subsequent letter:

“The fact of the matter is that I could not get over the figure you quote viz: £25, as previously advised you I paid £50 for them. So you can see there will be a loss 50% which for me being a poor woman, the loss will be great to me.”

(letter of 1 September 1898)

Eliza had not only spent money on buying the tablets, she had of course paid for the shipment and the insurance. An expense about which she does not speak but that several other dealers mention openly is the cost of bribing customs officials. Ferida Shamas, who was always direct and explicit in her letters, not only speaks about the bribes she was paying, but also plainly admits she was smuggling:

“Of course you are well aware that I pay T£10 [10 Turkish Liras] for smuggling every parcel and very often the authorities here seize my tablets”

(letter of 10 May 1900)

Many dealers openly acknowledged their violation of the ban on exportation, like Joseph Svoboda who wrote in 1895, ten years after the adoption of the law, that it was becoming more and more difficult to send artefacts to Europe because “strict prohibition for the exportation of antiquities has been enforced by the authorities” (letter of 26 June 1895).

If Eliza Kebaba was taken aback to hear that fake cuneiform tablets were part of her collection, finding that forgeries were circulating on the antiquities market was no surprise for the department. In a letter sent to Wallis Budge in 1904, the British assyriologist Reginald Campbell-Thompson who had been sent to conduct excavations in Nineveh by the British Museum writes that while in Aleppo looking for “antiques”, he had met Mr Homsy (or as he puts it “one of the Homsys”), whose company Homsy & Co was well known to the British Museum. This company had shipped thousands of artefacts to the department of Egyptian and Assyrian antiquities post 1884, on behalf of antiquities dealers in the region. The meeting seems to have particularly marked Campbell-Thomson, not only because of the number of forgeries he had seen but also because Homsy had tried to trick him: “such a collection of forgeries I never hope to see again – he tried them all on me, I didn’t buy” (letter of 13 February 1904). Despite this knowledge, forgeries regularly entered museum collections undetected. The Royal Museums of Art and History (RMAH) in Brussels for example recounts that a “fragment of a shell-shaped dish” (Fig 4) inscribed in cuneiform was given to them in compensation of four fake cylinder seals (not pictured) that they had bought from the antiquities dealer Ibrahim Gejou. The fragment had not been given to them by Gejou, however, but by the French assyriologist and archaeologist Henri de Genouillac, who had helped Gejou sell antiquities to museums for many years.

In 1898, the fakes in Eliza Kebaba’s collections had been identified before the purchase, and it spelt doom for her investment. Financially bruised and defeated, Eliza Kebaba eventually accepted the price offered by Wallis Budge, and confirmed receiving payment in December 1898. She would offer no other collection to the museum after this. Eliza Kebaba is one of the rare women to have sent artefacts for sale to the British Museum from Iraq. Based on the letters in the BM archive, this business was clearly dominated by men but women, however few, did partake in the trade.

Let’s not cry over spilt milk: the case of Rezooky Sayegh

Rezooky Sayegh contacted the museum in 1894, much earlier than Djemileh Sayegh and Eliza Kebaba above. Rezooky is one of many new dealers who suddenly approached the department between the years 1894 and 1897 to sell archaeological artefacts recently excavated in Iraq. This remarkable increase in first-time sellers might be explained by events narrated by a commission agent called Charles Pinches in a letter he sent to Wallis Budge in December 1894. In a One Thousand and One Nights fashion, Pinches’ letter contained the copy of another letter, one sent to him by an antiquities dealer in Baghdad called James Muir who wished to inform him of a discovery. In the summer of 1894, Muir writes, Iraqi excavators had discovered hundreds of cuneiform tablets on the site on which they were working, whose location was only described as “near Tello”: “the Arabs around that spot chanced to discover a large cellar (about 10 feet in height & 10 in length) full of bricks of different forms & sizes. […] Great difficulty is experienced in obtaining them especially lately, on account of the Turkish Government as the Antique dealers has to sink their money and bear the insults and fines of the Government.” As can be understood from Muir’s letter, the tablets had quickly found their way on Baghdad’s antiquities market. Rezooky Sayegh’s collection may have come from this newly discovered site.

Photograph by Abdul Reza Salmin, c. 1960. Two boatmen in the bay are standing on their long narrow boat with packages in-between them. Several steamships are in the background. Photo credit: HipPostcard

In his letter, Rezooky Sayegh was writing to advise Wallis Budge that he had sent a collection of cuneiform tablets on a steamship called the S.S. Uganda. Unlike Djemileh Hanna Sayegh and Eliza Kebaba, Rezooki was writing from Basra, where he was living and working in his family’s company called Hotz & Co. Rezooki seemed to have been especially troubled by the risks he was taking in smuggling the tablets. His letters show he was weary of the authorities to such a degree that he instructed Wallis Budge to only send letters to him via “Brindisi and Bombay”. This type of post, also referred to as the ‘English post’ by dealers, meant that the mail would transit through Italy and India, and would first arrive in Basra on steamships before being delivered in Baghdad. Wallis Budge was regularly asked by other dealers to avoid sending letters via the ‘Turkish Post’, which would go through Constantinople. The reason for preferring the ‘English Post’ is given by several dealers who mention that the authorities inspected all mail and telegrams in that period, and were especially vigilant in Constantinople and Baghdad. They were known however to be less effective in Basra. In his own letters to the BM, the antiquities dealer Henry Svoboda regularly asked Wallis Budge to address all his letters to him in Basra “in the care of the British Consulate” to avoid inspection, which shows the extent of these dealers’ networks.

Rezooki Sayegh waited for about a year to receive an evaluation for the tablets he had sent. When it came, he was not pleased. He was offered £10 for the lot (equivalent today to circa £1,365). Although it was not a negligible sum, he was greatly disappointed for reasons he does not divulge in his letters but which are echoed in other dealers’ letters. For example, by mid-1895, Henry Svoboda had also decided to stop selling to the BM because the purchase prices offered by the department were so low. In August 1895, he writes:

“I am sorry to see your very low offer for all the tablets and also very sorry to say I cannot see to send you some more.”

(letter of 29 August 1895)

Unwilling to barter and wait longer for a return on his investment, Rezooki Sayegh accepted the offer straightaway, remarking that “it is useless to cry over spilt milk and am afraid that your offer does not encourage me to make any further shipment to Europe.” He would not be heard of again by the department, but by all accounts he lived happily ever after, at least according to Joseph Svoboda who regularly wrote about his old friend in his diaries post-1895.

Life stories

Letters sent by antiquities dealers based in Iraq to the curators of museums in Europe and America are invaluable to reconstructing the manner in which Iraq’s cultural heritage was scattered all over the world in the late 19th century. This correspondence is not only witness to how smuggling operations were conducted post 1884, it is also invaluable to reconstructing the identities and life stories of the people this trade impacted. Beyond wanting to make money, it is difficult to imagine what other motivations may have moved people to smuggle artefacts in this period, and why they expressly dedicated themselves to enrich the collections of European and American museums. However, a number of antiquities dealers do speak explicitly about wanting to ‘serve the British Museum’ and to be ‘officially rewarded by the UK government’: their wish that their work be recognised will be explored in a future blogpost.

Note: The letters referenced in this article are not digitized.

Acknowledgements

This study could not have been conducted without the support of the British Museum’s archivists, especially during the pandemic restrictions of 2020 and 2021. I am very grateful to them, and to the curators of the Middle East department who generously provided information, as well as access and assistance.

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

she/her

Contributor (2021-22)

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at SOAS’ School of History, Religions, and Philosophies. My current project is based on the study of clay tablets inscribed with predictions (omens) written in the Old Babylonian language, and dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 2004-1595 BCE). The aim of my research is to investigate the content of these ancient predictions, the desires and anguish they express before unpredictable tomorrows, as well as the provenance of these tablets, with a focus on how most of these ancient Iraqi artefacts were bought by museums in Europe and the US from antiquities dealers trading from Baghdad, between the late 1880s to the late 1920s.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London

One Comment

Comments are closed.