We Need to Talk about the History of Rape

By Ana Nenadović

It seems impossible to deny the ubiquity of sexualised forms of violence against gendered bodies, and that things need to change. Yet rape myths not only prevail, they are consistently reproduced and reinforced. This is due to an overexposure and consequent desensitizing to rape. As Roxane Gay suggests in Bad Feminist (2014):

We have also, perhaps, become immune to the horror of rape because we see it so often and discuss it so often, many times without acknowledging or considering the gravity of rape and its effects. We jokingly say things like ‘I just took a rape shower’ or ‘My boss totally just raped me over my request for a raise.’ We have appropriated the language of rape for all manner of violations, great and small.[1]

Such language is not only careless but highly problematic, as Gay further clarifies:

I am troubled by how we have allowed such intellectual distance between violence and the representation of violence. We talk about rape, but we don’t carefully talk about rape.[2]

Language as a medium of narrativisation can perpetuate patriarchal structures and violence. But contemporary representations also challenge these. In Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s novel The First Woman, for instance, the protagonists Nsuuta and Kirabo reflect on the power of storytelling through storytelling. Nsuuta, the grandmother, shows Kirabo how stories have been used throughout time to create gender norms and ultimately contribute to the subjugation of gendered persons.[3] In this article I interrogate the ubiquity of representations of rape across the history of humankind in stories, paintings, music, and films. A critical engagement with these representations is necessary because they determine our understanding of sexualised violence to a large extend. Here, my objective is to examine representations of rape, and to juxtapose aestheticised representations with critical portrayals of sexualised violence, and where better to start than religion and myth.

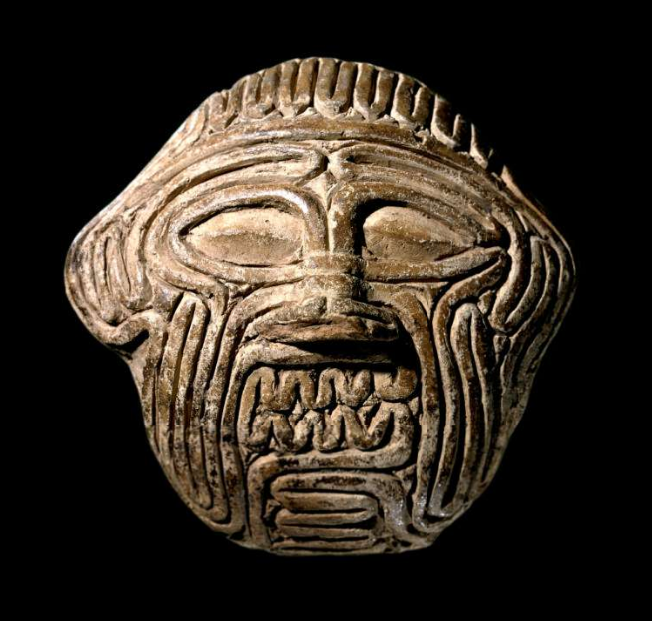

Whether it is Christian biblical stories of Lilith or Judith, the varied stories of the orishaYemaya in Western Africa, the Caribbean and Brazil, or ancient Greco-Roman mythical figures like Europa or Medusa, mythologies are permeated by rapes. [4] They are neither questioned nor critically examined, but simply accepted as part of gendered bodies’ lived experiences and this cosmological place. They are constitutive for the preservation of rape myths and the normalisation of sexualised violence against gendered persons. In her article The Virgin in the Mirror, Elizabeth Pérez summarises the stories about Yemayá in the Afro-Cuban santería tradition as follows:

One might wonder how Yemayá became a mother if, as her mythology asserts, she had little desire for men or interest in attracting them. Her myths answer the question straightforwardly: Yemayá was raped. The subject of violation pervades the mythology of Santería related in divinatory verses and ritual utterance, but seems peculiarly pronounced in the case of Yemayá.[5]

According to the myths, Yemaya was raped. However, the accounts vary on the question of the perpetrator; it is either her son, her husband or other orishas who rape her. If an orisha can bear rape and birth other orishas and the ocean (Cuban version) or the river Ogun (Yoruba version), then shouldn’t humans silently bear sexualised violence as well? In some versions of the rape of Yemayá, the creators emphasise her repulsion and her intention to flee from her rapists, including her firstborn son.[6] But this should not be taken to imply a critical deconstruction of rape in the patriarchal understanding. On the contrary, it again centres the gendered body in the rape narration and neutralises the perception of the perpetrator’s active role in rape. Thus, historically and mythologically, rape became a gendered persons’ problem that simply happens to them, a phenomenon often reproduced in media and societies to this day.

Rape has not only been present in human history, it has been used to explain shifts in history. The Roman empire being a notorious example for (mis-)using stories of the rapes of women to account for structural and political changes. Sextus Tarquinius’ rape of Lucretia, a noblewoman in the monarchical Roman empire, and her subsequent suicide are adopted as explanation of the empire’s transition from monarchy to republic (res publica). The story that has become a frequent motif in visual arts (Rembrandt’s Lucretia from 1664)[7], music (Benjamin Britten’s opera The Rape of Lucretia) and literature (William Shakespeare’s long poem The Rape of Lucrece).[8] By aestheticising the crude gender-based act, the violence is neutralised and what remains is a romanticised encounter between Sextus Tarquinius and Lucretia. Though something dishonourable lingers, it is Lucretia who is overcome by feelings of shame and guilt that finally lead her to suicide. The victim is the centre of attention, and it is up to her to find a solution that will re-establish her honour. The notion of rape as the fault and responsibility of the victim finds one of its strongest and most persistent examples in the myth of Lucretia.

Despite the prevalence of sexualised violence, it has been a taboo subject throughout history. Most importantly, it has been constructed as a problem that concerns gendered persons, not ‘normative’ people, that is, men. Only recently has the burden of blame shown signs of shifting to the perpetrator. Campaigns on social media such as #NiUnaMenos (2015, Argentine), #EndRapeCulture (2016, South Africa) and #MeToo (2006/2017, USA) have given some victims of sexual harassment and sexualised violence the possibility to share their stories and raise awareness of the power of representation. But it has taken decades for victims and their allies to gather this strength. The validity of the male gaze, a term coined by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 article Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, has been critically examined and subverted in productions of the past few years. A notable example is the film Citation (2020, Nigeria), written by Tunde Babalola, directed by Kunle Afolayan and starring Temi Otedola. Citation depicts the prevalence of rape culture on university campuses and deconstructs various rape myths all while demonstrating how these are intrinsically embedded in patriarchal structures and hierarchies.[9] Citation also emphasises is that we are not yet living in a post-rape and postfeminist era, but still in an era of rape culture(s).

Needless to say, these few examples are only a glimpse of historical representations of rape continue to pervade the modern psyche. The inherent links between discourse, representation and perception of sexualised violence show us how each element impacts the others. Hopefully, this brief reflection on rape and its representations demonstrates that talking about rape culture(s) needs to continue.

Editor’s Note: To read more from Ana about this topic, please follow this link to her forthcoming book, out in July 2023.

References

[1] Roxanne Gay, Bad Feminist: Essays, Harper Perennial: New York, 2014, 129.

[2] Italics added. Gay, Bad Feminist, 132.

[3] Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, The First Woman, Oneworld: London, 2021.

[4] The orishas are spirits in the Yoruba religion of West Africa and in the African Diaspora (i.e. Cuba, Brazil). They are sent by Olodumare, the supreme god, to assist humans and help them navigate life on earth.

[5] Elizabeth Pérez, “The Virgin in the Mirror: Reading Images of a Black Madonna through the Lens of Afro-Cuban Women’s Experiences,” The Journal of African American History 95.2 (2010): 208.

[6] Pérez, “The Virgin in the Mirror,” 208-209.

[7] Lucretia, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1664, oil on canvas, see https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.83.html [accessed 20/03/2023].

[8] See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50474/the-rape-of-lucrece [accessed 20/03/2023].

[9] Kunle Afolayan, Citation, (film) Netflix, 2020. See also https://www.imdb.com/title/tt11481312/ [accessed 20/03/2023].

Ana Nenadović

she/her

Ana Nenadović is a lecturer in Global Liberal Arts at SOAS University of London. Her research interests include Gender and Queer Studies and Hip Hop Studies. She focuses on cultural and literary links between Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean. She is co-editor of the collection América Latina-África del Norte-España (2020).

Twitter: @Nenadovic2Ana

SOAS Profile: Dr Ana Nenadović

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London