Ibrahim Elias Gejou and Old Babylonian Omens

by Nadia Ghanem

“Ibrahim Gejou called on us, he is buying antiques and sending to Paris for sale!”

Joseph Svoboda, Diary 49, Monday 26 June 1899

Ibrahim Elias Gejou (pronounced Jejoo) is a well-known name to scholars who look into the provenance history(1) of Iraq’s tangible cultural heritage. Gejou (1868-1942) was an Iraqi-French antiquities dealer who sold a vast number of artefacts from Iraq to European and American museums. He is behind the sale of several of the texts I study, 4,000 year-old predictions inscribed on clay tablets called ‘Old Babylonian omens’ in modern scholarship. The investigation of these texts’ journeys from Iraq is part of my research as a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the SOAS History department, which includes retracing how these clay tablets arrived in the collections that hold them today.

I began to see a link between Ibrahim Elias Gejou and the Old Babylonian omen tablets I study when compiling a list of their current locations. There are around 275 Old Babylonian omen tablets spread across the world. I wanted to understand how these ancient texts arrived in London, Paris, Berlin, Geneva, Leiden, Chicago, Yale, Moscow, and Hokuto – as so few are in Iraq’s museums today, and who supplied these collections. Museum archives keep old records and correspondence about the acquisitions of the objects they have collected over the years, whether from excavations or from purchases, with dates and names. With the help of archivists and museum curators who assisted me during the many lockdowns of 2020, my list of the provenance history of these tablets began to tell in detail a story whose general lines are well-known to specialists: the majority of Old Babylonian omen tablets in museums today do not come from documented excavations, they were purchased from antiquities dealers from the late 1880s to the 1920s, and many of them were bought from Ibrahim Elias Gejou.

To begin to tell the tale of how Old Babylonian omen tablets were traded at a time when the exportation of artefacts was forbidden by Ottoman law, this blogpost will first introduce Ibrahim Elias Gejou, aided by the diary entries that Gejou’s old friend Joseph Svoboda (1840-1908) wrote about him (diaries digitized on the University of Washington’s website by the Svoboda Diaries Project). This blogpost is one in a series that will investigate the names and activities of Iraqi archaeologists active in the late nineteenth century, like Daud Thoma, and the now forgotten Amran Ibn-Hamud, as well as Iraqi antiquities dealers linked to Old Babylonian omen tablets, both those who sold artefacts infrequently to make a little profit like Joseph Svoboda and those who made it a profession like Ibrahim Elias Gejou. The series will then follow on to discuss the environment that enabled the trade of ancient Iraqi artefacts in that period, despite the legal ban.

Old Babylonian omens: 4,000 year-old predictions written on clay tablets

If in the middle of the oil two ringlets pop up, one big, one small,

Prediction based on observing oil on water,

the man’s wife will give birth to a male child;

If I perform this for a sick person: he (or she) will recover

from an OB tablet in the Yale Babylonian Collection, YOS 10 57, line 6.

Old Babylonian omens are texts that record lists of predictions made by diviners in a language modern scholars call the ‘Old Babylonian language’. The texts are inscribed on clay tablets in a script termed cuneiform, a Latin word that points to the wedge-like shapes that a stylus with a triangular-tip makes when impressed on a soft clay surface. The Akkadian language has its own term for a wedge and triangle: a santakku.

Early attestations of cuneiform come from tablets mostly found in Uruk, in the south of Iraq, dated to c. 3200 BCE. While initially pictographic, cuneiform developed as a logographic and syllabic system to write Sumerian and Akkadian. Attestations of cuneiform writing were also found in other countries in Southwest Asia like Syria, Iran, and Turkey, where the script was used to write several other languages, for example Hittite in Turkey, Eblaite in Syria, Elamite in Iran, and Urartian in Armenia. Cuneiform writing had a long life span, from the third millennium BCE until it fell out of use by the turn of the first century AD. Clay remained the writing support of choice: tablets are a like our sheets of paper today, they are just thicker and firmer, and could be written on both front and back, as well as on their sides.

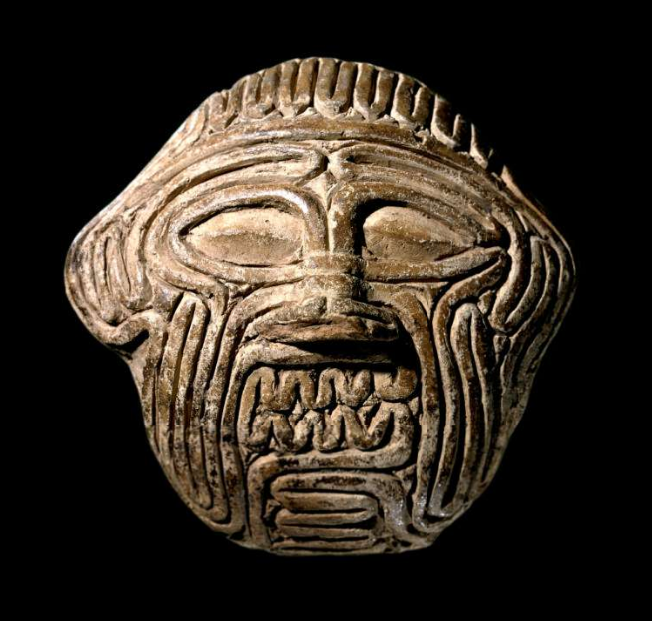

Old Babylonian omen tablets can be long or short, round or rectangular, and some even represent internal organs like livers and lungs, with predictions inscribed on them. Old Babylonian liver models found during French-led excavations in Mari (modern Tell Hariri) in Syria during the campaign of 1935-1936, are the most famous examples:

Other tablets feature drawings on one face, modelled on the surface of the clay, with one prediction inscribed on the back. An omen sentence is usually framed as an ‘if’ sentence, typically ‘if x is observed, then y could happen’. The below are famous examples of tirānu-models: shapes that the coils of the intestines could have taken, like the shape of the face of Huwawa, the guardian of the cedar forest in the epic of Gilgamesh, or that of a scorpion:

(the inscription is on the back), BM 116624. Photo credit: British Museum website

“If the coils of the intestines are like Huwawa – omen of Sargon who controlled the land written by Warad-Marduk, the diviner, son of Kubburum the diviner”

“[If the coils of the intestines are like a scorpion – omen of Sargon]

the king will have no rivals written by Aham-arši, son of Lipit-Ištar, the diviner”

The term ‘Old Babylonian’ denotes a time period, dated to c. 2004 BCE to 1595 BCE (middle chronology), and to a stage in the Babylonian language distinguished through a number of features specific to that period. Babylonian is one of the varieties of the Akkadian language, spoken and written in ancient Iraq for over 2,000 years. Akkadian, a dead language now, is the earliest Semitic language known to date, based on written attestations. Modern languages part of the Semitic family are Arabic, Hebrew, and Assyrian for example.

The dates given for the Old Babylonian period change depending on the point at which scholars begin to recount events: from 2004 BCE which marks the fall of the Third Dynasty of Ur, or from 1880 BCE, the year king Sumu-la-El established his royal dynasty in the city of Babylon. The fifth king of this dynasty would be the famous king Hammurabi. The end of the Old Babylonian period, 1595 BCE, marks the year in which the Hittite army sacked the city of Babylon.

Native speakers of English, French, German, and Hebrew have recorded stories once told in the Old Babylonian language on BOPLAR, part of the SOAS’ History department webpage. The page awaits similar readings by native speakers of Arabic, Assyrian, Turkish, and Persian.

In ancient Iraq, and throughout neighbouring countries in Southwest Asia, diviners were men and women trained to predict the future by reading clues hidden in nature by the gods. These messages could be read in a number of natural events: in the movement of planets and stars, in the weather, or in the manner birds flew for example. Clues could also be provoked by questioning the direction that oil would take when dropped on the surface of water in a bowl, or by examining the entrails of animals to look for messages and warnings in the colours, shapes, and marks of the internal organs of sheep and birds.

Trying to find what the future held was a serious endeavour. It was a science on which the State counted to take a number of crucial decisions like knowing when the best time might be to build a place of worship, or to go to war, or whether to prepare for natural disasters that could endanger food production and bring famine. Private individuals with worries closer to home than those of statesmen also consulted diviners to get an idea of the surprises fate may have held in store for them and their families. A prediction based on observing a feature called the ‘footmark’ on the gall bladder of a sheep states that “If there are eight footmarks – the man will reach old age; he will see his grand-children” (YOS 10 44, line 70, Tablet in the Yale Babylonian Collection). And like us today, people also worried about epidemics: “If the heart is full of red grain like warts – there will be an epidemic (YOS 10 42, lines 26-27, tablet in the Yale Babylonian Collection). Seeking out a divinatory reading was very likely also a way of managing stress by preparing oneself for what life would throw at you and having the chance to dispel potential future disasters by performing a number of rituals, which are preserved in texts called ‘Namburbi’ dated to the first millennium BCE.

The Iraqi-French antiquities dealer Ibrahim Elias Gejou

Ibrahim Elias Gejou is perhaps one of the easiest antiquities dealer’s life to reconstruct thanks to modern bureaucracy. Gejou was awarded France’s highest honorific order the Légion d’Honneur (the Legion of Honour) in 1926, and was made a Chevalier (a Knight) of this order on 9 February 1926 to officially reward what his dossier calls “his help in serving France’s influence in the Orient”. The order was given to recognise Gejou’s work in enriching the collections of many French national collections, including those of the Louvre Museum, and of the National Library (the Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

His ‘Knight’ file registers him as an ‘archaeologist’, not as an ‘antiquities dealer’, a title Gejou used in his own letterheads from at least the early 1910s.

The Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur award is the result of an administrative process that required Gejou to submit an application with personal information like his date and place of birth, and a list of his previous activities. This file still exists today and contains many useful pointers to reconstruct cornerstone dates in Gejou’s life. It was digitised by the National Archives and can be found on their open access website.

Gejou was born on 12 May 1868 in Baghdad. His parents, of Armenian origins, were called Ferida Kroumy and Elias Gejou. According to Gejou’s old family friend Joseph Svoboda (introduced below), Elias worked as a broker for the Lynch Brothers’ shipping and trading company in Baghdad (Svoboda Diaries 42, p.1). The Gejous also had another son, Isaac, and two daughters, Sarah and Loulou. In his ‘Knight of the Legion’ application, Gejou writes that he had worked as an interpreter for the French Consulate in Baghdad between 1881 and 1887, when he was between 13 to 19 years of age. He had planned to leave Baghdad to study medicine and had enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine in Paris. The date of Gejou’s arrival in France is still unknown to me, but his friend Joseph Svoboda records in his diaries that Gejou was returning to Baghdad from Bombay on Monday 10 June 1889 (Svoboda Diaries no. 33 p.132). Gejou may have left for France after his return from India, in any case, by early 1890 he was settled in Paris. The date of his marriage to his first wife Julie Eugenie Deschaumes places him there on 4 January 1890, at the age of 21.

It may be that Gejou began his studies and then changed his mind, or pursued something else entirely once in France, but by 1894 Ibrahim was making his first sale to the British Museum. He was 26 years old then and already professionally engaged in the antiquities trade with his brother Isaac, as attested by Joseph Svoboda’s, in the following diary entry written on 30 October 1894: “Isak son of Elias Jejo is coming to buy antique tablets of Tello” (Svoboda Diary 40, p.7). The many letters Gejou sent to museum curators show that throughout his life he regularly returned to Baghdad to visit his family. While there, Gejou would buy ancient artefacts and would have them shipped to Europe by companies that would deliver the crates directly at the door of private collectors and museums in Europe. In 1899, Gejou and his friend Jeboory Asfar had used a steamship company called Strick & Co to sell 780 tablets to the British Museum for £100 pounds (a sum equivalent to around £12,500 today). Many of the tablets of this lot were small and broken, but among them were five Old Babylonian omen tablets, three of them rare examples of predictions made by using sesame oil.

Gejou and others like him made the trade of antiquities their profession in the late nineteenth century, despite Ottoman law forbidding the exportation of ancient artefacts outside of the Ottoman Empire, of which Iraq was then a part. The first such law put in place in 1869 to address some of the issues that arose from the massive exportation of artefacts by foreign excavators did allow the purchase and sale of antiquities within the Ottoman Empire. From an initial seven articles, the law was extended to 36 articles in 1874 and revised in 1884 (see a publication of the legal text in French translation here). It was in the subsequent revision of the law in 1906 that the authorities forbade the sale of antiquities across Ottoman-controlled territories.

Like most antiquities dealers, Gejou did not know the categories of the objects he traded, nor their datation, whether they were inscribed or not. To assess the monetary value of the objects he sold, Gejou would ask scholars for historical information. Gejou was good friends with the Swiss Assyriologist Alfred Boissier for example, and with the French curator of the Louvre museum Francois Thureau-Dangin, also a renowned Assyriologist.

By 1904, Gejou had remarried (he had divorced Julie Eugenie in 1899) and was making a life with Ernestine Picardat in Cosnes-sur-Loire in France, south of Paris, while also keeping a home in Paris on Avenue de Breteuil. He obtained French citizenship by decree on 31 May 1913 and, when the first World War began, he was enrolled in the army as a soldier. Gejou was injured in 1914 and was allowed to stay at home to recover for a few months, during which time he kept in touch with many of his buyers who continued to purchase artefacts from him during the war, as letters to museum curators from that time illustrate. The artefacts Gejou sold to museums in the USA helped him and his family survive some of the hardships of the first years of the war.

Gejou traded so many artefacts to Europe and the USA, that by 1938 he had sold almost 18,000 pieces to the British Museum alone – a staggering amount for a single person to trade, even over a period of 40 years. The British Museum is one of the rare public institutions with an ‘Ancient Near East’ collection that makes available online, freely and openly, the names of the sellers from which it bought the objects of its collections. The list of objects bought by the British Museum from Gejou is easily searchable. Typically, an object entry on the website lists the names of the people who sold, donated, or brought it from an excavation, as well as the date it was registered in the collection, like the below referenced as ‘BM 113190’ bought from Gejou in 1914. Few museums that hold ‘Ancient Near East’ collections make the names of the sellers or donors available on their website, a type of information-sharing that should be standard practice.

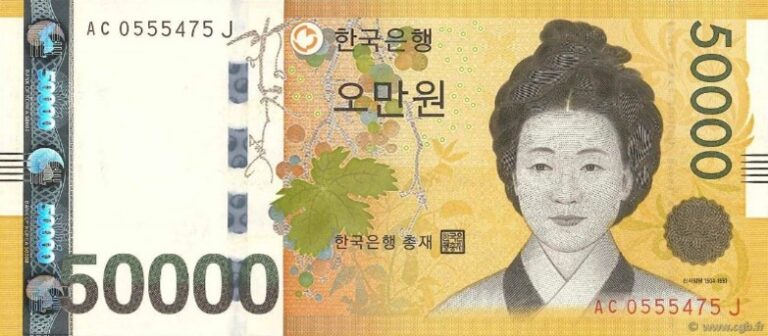

Bought by the Louvre from Gejou in 1925. Photo credit: the Louvre Museum ‘Collections’

The BM is not the only museum to which Gejou sold artefacts in bulk. The Louvre Museum’s new website ‘Collections’ (a database launched in March 2021 that provides information on the previous owners of the objects of its collections) lists 1,050 objects bought from Ibrahim Elias Gejou. This number will no doubt increase as the Louvre continues to enrich its entries. Gejou also sold many artefacts from Iraq to the Yale Babylonian collection. He is probably also behind the sale of one of the most important groups of Old Babylonian omen tablets there today, the provenance of which is currently being studied. By the time Ibrahim Elias Gejou passed away on 12 July 1942 in his home in Cosne-sur-Loire in France, he had become one of the most active antiquities dealers of ancient Iraqi artefacts of the late nineteenth century. His life partner, Ernestine Picardat passed away a few years later in 1951, also in Cosne. Their home, which the Gejous had called the ‘Gudea villa’, still exists today.

Ibrahim Elias Gejou and Joseph Svoboda’s diaries

Gejou’s friend Joseph Svoboda, mentioned above, was well acquainted with the Gejou family. For several months, Joseph Svoboda was only one of many names in my provenance list. I had come across him because he too had sold an Old Babylonian omen tablet to the British Museum in 1897. But in the autumn of 2020, while hoping new information about Ibrahim Elias Gejou would pop up in my google searches, I came across the “Svoboda Diaries Project”.

The Svoboda Diaries is a project led by a team of researchers at the Ottoman Texts Archive Project (OTAP) based at the University of Washington, who have been digitizing, analysing, and writing about Joseph Svoboda’s diaries since 2006. They have created a digital collection of the diaries and an online platform called The Svoboda Diaries.

Joseph Svoboda was born in Baghdad on 17 October 1840. His mother, Euphemie, was from an Armenian family of Istanbul. His father Anton, an Austro-Hungarian glass merchant, had come to Baghdad to establish his business there. Euphemie and Anton married “in Baghdad on 12 February 1825 and had eleven children”.

On 12 February 1862, Joseph Svoboda began working in Baghdad as an officer on the steamships of the Euphrates and Tigris Steam Navigation Company, a company part of the British-owned Lynch Brothers Trading Company, and on that day he began writing a diary. He would keep his diary writing habit going until his death in 1908. Joseph wrote daily entries from 1862 to 1908, in English, a language he spoke fluently since his stay in India, where he lived for a few years with his brother Alexander Sandor Svoboda. Joseph ended up writing 61 diaries, and kept them all. After his death, they went through the hands of several people until they reached the Iraqi National Museum of Antiquities and the National Manuscript Center.

part of the boat fleet of The Euphrates and Tigris Steam Navigation Co. Photo credit: Tinco Lyncklama website – Adventurer and Socialite

The survival of these diaries makes for a fascinating story. On their website, OTAP’s team recounts that in 2006, they were contacted by the architect Nowf Allawi, who had been working with a descendant of the Svoboda family, Henry Svoboda. Henry was writing a history of the Svoboda family together with Nowf, based on the study and transcriptions of the diaries made by Margaret Makiya at Al-Hikma University in Baghdad, who had worked extensively on the diaries in the 1970s. The diaries had come into the collection of Al-Hikma university when it received as donation the private library and papers of the Iraqi historian Ya’qub Sarkis. When the university was nationalized, the diaries came to the Iraqi National Museum of Antiquities and the National Manuscript Center.

For 46 years, Joseph wrote about his life on board a ship that looked after the Baghdad-Basra route, transporting passengers and many kinds of cargo, like coal, wool, and liquorice roots. One of the route’s vital functions was also to ensure the delivery of mail received from Bombay. Next to his records of the private and public events that affected his life, whether they were celebrations, disputes, political upheavals, or national health scares, Joseph kept a record of the names, trades, and personal stories of his passengers and friends – including Ibrahim Elias Gejou.

Photo credit: the Svoboda Diaries website

Photo credit: the Svoboda Diaries website.

Joseph Svoboda regularly mentions Ibrahim Elias Gejou and his family, as the two knew each other well. Diaries 47 to 49 (1897 to 1899) in particular name Gejou often because in 1898 he had been caught up in a dispute between Joseph and Alexander, Joseph’s only son. In 1897, 19 year-old Alexander had gone to live in Paris with Ibrahim. His parents, Joseph and Eliza, had brought him there personally and quickly seemed to have regretted it. By 1898, Alexander had fallen in love with a French girl, Marie Josephine Derisbourg whom he decided to marry against his parents’ wishes. Through 1898 (diary 48), Joseph was frantic, sending many telegrams to Paris to convince his son to return home, and blaming Ibrahim for some of his son’s actions:

“What an answer and what a daring, he must have lost his head and he must have been taught by the woman he loves or by Ibrahim Gejou”

Saturday 6 August 1898, Svoboda Diary 48, p.4

Joseph names the Gejous regularly in many of his diaries. It is through his diary entries that I know the name of Ibrahim’s sisters for example. On Thursday 15 June 1899, Joseph writes “I called on Antone Marine and then went to call on Ibrahim Gejou at his father’s house but did not find him at home, I sat with his mother and the two sisters Sarah and Looloo” (Svoboda Diary 49, p.63). Joseph knew Elias, Ibrahim’s father, and regularly bumped into Ibrahim and Isaac, Ibrahim’s brother, in the streets of Baghdad.

“I called on Eliza and Adoola my cousins, and coming home I met Ibrahim Gejou in the Street”

Friday 16 June 1899, Svoboda Diary 49, p.64

Joseph’s short notes about the Gejous provide rare glimpses into Ibrahim’s family life in Iraq, and about his regular journeys from Paris to Baghdad to visit his family and to organise his trade. Joseph’s diary entry dated to Monday 13 June 1898 records that Ibrahim was buying and selling other goods than antiquities from time to time, like shoes and perfume that his brother Isaac would sell in Baghdad: “Ibrahim Gejou has sent 3 cases containing shoes and perfumery to his brother Isak for sale” (Svoboda Diaries 47).

The Svoboda diaries are a rich source of information about Ibrahim Elias Gejou’s life and the environment that made this trade possible. They also are invaluable for the names and anecdotes Joseph wrote about the Iraqi archaeologists and antiquities dealers he met throughout his life on board ship.

Iraqi archaeologists and antiquities dealers in the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century

Modern retellings of the world-renowned finds that were made in Iraq from 1843, when foreign explorers and government consuls began to excavate ancient sites in the country, rarely mention the names of the Iraqi archaeologists who took part in the unearthing of their own cultural heritage. Many of these names survive in old excavation reports and in precious private documents like the diaries of Joseph Svoboda.

As a steamship officer for 46 years, Joseph encountered many people engaged in the search, and the transport, of ancient Iraqi artefacts. Joseph met foreign archaeologists like the French Ernest de Sarzec, and museum curators like Wallis Budge of the British Museum. He was close friends with influential local figures like Jeboory Asfar, whom de Sarzec had met in 1877, an encounter that had led de Sarzec to excavate in Tello. Joseph Svoboda also met many Iraqis who were archaeologists in their own right, not simply ‘assistants’ to Europeans, and antiquities dealers from all walks of life. All these actors were part of the same network. From the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, all were going up and down the Tigris and Euphrates from Baghdad to Basra, intent on finding ancient artefacts, to collect, sell, or keep. The foreign excavations conducted in Iraq since 1843 had long opened that door.

To be continued…

References

(1) Dr Magali Dessagnes’s Doctoral Thesis La Circulation des Tablettes Mathématiques focuses on Ibrahim Elias Géjou’s sales of mathematical cuneiform tablets.

Nadia Aït Saïd-Ghanem

she/her

British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at SOAS’ School of History, Religions, and Philosophies. My current project is based on the study of clay tablets inscribed with predictions (omens) written in the Old Babylonian language, and dated to the Old Babylonian period (c. 2004-1595 BCE). The aim of my research is to investigate the content of these ancient predictions, the desires and anguish they express before unpredictable tomorrows, as well as the provenance of these tablets, with a focus on how most of these ancient Iraqi artefacts were bought by museums in Europe and the US from antiquities dealers trading from Baghdad, between the late 1880s to the late 1920s.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London

3 Comments

Comments are closed.