Mavo and the Space for Freedom: Masturbation, Anarchy and Autonomy in 1920s Japan

by Joe Nickols

In Japan, the start of the twentieth century saw the government increase its stranglehold of power and authority over its citizens. The militarisation and industrialisation of Japan was in overdrive and resulted in the continued expansion of the Japanese Empire. The aggressive capitalist programme of Japanese modernity prioritised industrial automation over personal autonomy. To create an effective workforce Japan implemented a simplification of human identity based upon binary matrixes. The Eurocentric male-female gender binary became central to the Japanese colonial ideology (as discussed in my previous article). This caused an artistic reaction during the Taisho period (1912-1926), which critiqued this authoritarianism and sought to open up spaces of personal freedom. At the forefront of this creative revolution was the interdisciplinary collective known as Mavo, founded in 1923 and led by Murayama Tomoyoshi (1901-1977). Using anarchic principles of self-satisfaction and self-emancipation, Mavo challenged the government’s authority over the individual. Through gender non-conforming performance art, photography, installation, and dance Mavo’s oeuvre represents a comprehensive drive for the freedom of the self. This article will briefly examine the ways in which Mavo proposed an alternative social matrix to the government’s regimental drive for conformity and control. After a brief introduction to the historical era, I will then offer a close reading of Murayama’s 1924 Kitanai Odori (Dirty-Earthy Dance), a piece focused on masturbation, anarchy and autonomy, to illustrate Mavo’s artistic resistance.

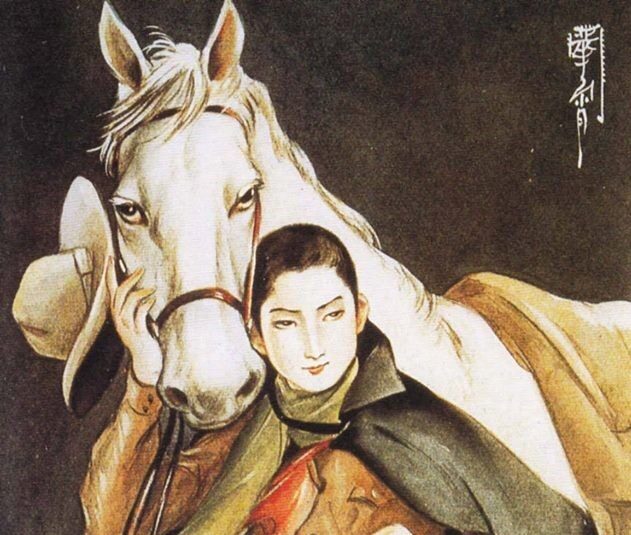

The Japanese government’s authoritarian dominance increased during the 1920s, particularly after the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, in which much of Tokyo was destroyed and over 100,000 inhabitants were killed. The aftermath of this disaster was charged with xenophobia and establishmentarianism. The government used the social and actual chaos of the earthquake to assassinate left-leaning figures of the period, such as Ōsugi Sakae and their family.[1] Japanese vigilantes seized the opportunity to massacre many Chinese and Korean residents, which went unpunished as police actively condoned this violence against foreigners. As many creatives were seen to house foreign sympathies, it was also a dangerous time for these communities. The space for freedom was shrinking. Leading Mavo members were warned to alter their European-inspired appearance to escape persecution. Mavoists were associated with an androgenous bob-like hairstyle and the Russian-style rubashka shirt (Fig. 1). These elements not only threatened the commands of gender performance, but also signified European sympathies. The stranglehold of government over self-autonomy culminated in 1925 with the enactment of ‘The Peace Preservation Act’, which gave the police powers to imprison any person who undermined or threatened the government’s policies. By 1928 the death penalty could also be implemented.

Sociologists Kon Wajirō and Gonda Yasunosuke both conducted ethnographic projects during the 1920s to explore the developing modernism of Japan. Both concluded that embodiments of personal variability could not be accommodated in the newly industrialised state.[2] As Taisho officials felt that the collective national mission took precedence over personal pleasure and expression, Mavo’s depictions of non-conforming sexuality and gender became a potent political protest. Mavo were considered a dangerous influence on society. Multiple members were arrested and subjected to hostile conditions. Yanase Masamu (1900-1945) experienced particularly brutal police oppression, being beaten and bayoneted by military police over a 5-day period. Ideologically antithetical to the government, Mavo’s anarchist ideals called for minimal interference by the state into citizens’ personal lives. These anti-government sentiments were based upon the writings of the Hungarian anarchist Max Stirner (1806-1856).[3] Stirner asserted that the autonomy of the individual was the ultimate weapon against the state. The body was the locus for liberation as it could represent complete rejection of governmental commands. Furthermore, Stirner proposed that by constantly transforming and developing the body, an individual could attain absolute knowledge of the self. This knowledge of the self would make state control unnecessary and allow for incontestable personal freedom.

Through both theatrical performances and installations, Mavo represented the existence and validity of subaltern bodies that were otherwise being erased. These performances proposed alternative ways for individuality to co-exist within a group dynamic, opposing the government programme of conformity. Many performances were improvised, with members responding to the actions of each other, synthesising individualism within a collective. This is exemplified in Dance That Cannot Be Named (Na no Tsukerarenai Odori) (1924) (Fig. 2), where Murayama and Okada Tatsuo (1900-1937) adopted transgender appearance and danced wildly, whilst Takamizawa Michinao (1899-1989) produced the sonic accompaniment on “sound constructors”.[4] The performance took place in a University Hall and elicited an excited reaction from the audience. By performing outside a theatre, Mavo were destroying the regulatory boundaries of permissible cross-dressing. This had been set by the 1873 Tokyo Misdemeanour Code which prohibited bodies from presenting as a gender that differed from their assigned sex, with the singular exception of Kabuki and theatrical performances. Though the government permitted actors to “cross-dress” on stage, this social exemption of transgender embodiment was constructed to allow the continuation within Kabuki theatre for men to perform state-sanctioned caricatures of womanhood.[5] The law was not designed to allow individual performers interpretation of gender construction. By performing socially disobedient actions in dislocated spaces beyond the “stage”, Mavo actualised an alternate construction of reality that embraced personal freedom. Jay Prosser proposes that by inducing prohibition on socialised identities (such as homosexuality or transgender), governments produce a cultural unnameability that ensures a traumatic loss of selfhood as the identities can no longer be articulated.[6] By corporeally displaying alterity in public spaces as Mavo did, the body endeavours to bear its literal truth, and prevents the completion of cultural unnameability and erasure.[7]

The embrace of androgenous and transgender appearances by Mavo members was essential to their public protest. Regulating gender was crucial to the government’s authoritarian mission. From 1868, the year Japan officially reopened its borders to Euro-American trade, gender binaries were increasingly entwined in cultural, temporal, and social constructions. Maleness increasingly represented the unquestionable progression of Japan towards a modern and strong Imperial future. Whilst femaleness was conceptualised as the bridge to a lost Japanese cultural past.[8] Men were entrusted to construct a dynamic future, whilst women were required to connect Japan to an idealised and imagined past. Both of these concepts served the government’s expansionist programme as it perpetuated a public duty to emulate the ideals of the past in the creation of Japan’s shared future. Representations of non-conforming gender, therefore, rejected this national mission. Transgenderism represented an alternative temporal reality that was grounded in present actions and opened up new future possibilities.[9] By existing beyond the commands of gender binaries, Mavo’s performances emphasised the complexity of the body and the need for an alternative trajectory of futurehood in Japan, one based on autonomous self-construction.

During the Taisho period the government discouraged masturbation as it contravened the state’s contextualisation of sexuality as purely procreative.[10] For Mavo, who were against the proliferation of heteronormative civilisation, masturbation became the symbolic act of defiance against nationalism.[11] Masturbation acts as a proclamation of autonomy, demonstrating the fulfilment of the body by the body itself. Fellow anarchist and Mavoist Hagiwara Kyōjirō (1899-1938) posited that “art is human masturbation” as the use of imagination is engaged in both autoerotic actions and art production.[12] Within anarchism, masturbation was an important practice as it prioritises the self and is an act of pleasure for its own sake.[13] Both Hegel and Stirner imply that the ideals of personal ownership and self-expression can be encapsulated in masturbation. As the body and mind are contained in an act of self-service removed from the external world, calling forth the unique desires of the internal mind, it is the ultimate declaration of the self.[14]

Murayama’s photographic series Kitanai Odori (trans. “Dirty-Earthy Dance”, 1924) (Fig. 3), displays Murayama’s body in the throes of an ecstatic nude performance, demonstrating a visual embodiment of an emancipated self. The singularity of Murayama’s nudity and the sensuality imbued through the postures and flowing hair fuel the imagery with autoeroticism. The masturbatory tonality asserts the images as investigations into a selfhood beyond state control. Though nude, Murayama’s face and body are never fully exposed, maintaining an ambiguity that denies direct recognition of “Murayama” onto the body. Judith Butler writes that to be “called” forth by others, or society, assigns a controlled subjecthood to the body. This appellation then forms the identity of the individual externally; simultaneously erasing the physical, psychological, and emotional experiences of the body.[15] Murayama, through the ambiguousness of the body and face within the images, denies the possibility of being assertively “called” into society through visual recognition. In denying appellation, Murayama denies their subjecthood within society.

Murayama’s sensuality in Kitanai Odani invokes a sexuality that is contextualised only by the singularity of Murayama’s body and mind. Charged with autoeroticism, the photographic series also demonstrates a removal from social engagement. Murayama never acknowledges the presence of the camera, their actions performed without awareness of the viewer. This fuses the primacy of bodily pleasure with the anarchic removal from social commands. The subversive power of sexual freedom over industrialisation is further demonstrated in Yabashi Kimimaro’s (1902-1964) My Onanism (Fig. 4). Circulated in the fourth issue of Mavo Magazine, the work displays an assemblage of varying industrial materials interrupted by a woman’s white sock. Through invoking onanism in the title of the work, Yabashi was deliberately disobeying Taishō civility. The title automatically encourages the sexualisation of the work’s contents. The sock prompts the viewer to imagine the body that discarded it, inviting the fetishization of the object. As this act of constructing an imagined body is mirrored in masturbation, where an individual fantasies their body as or with another, the sock fills the assemblage of otherwise mechanical material with human desire. The anonymity within the work acknowledges that the construction of sexual desire is unique to each observer, built up over a lifetime of experiences. By disembodying the figure of sexuality, the owner of the sock, Yabashi allows a phantasmic embodiment of sexuality to be constructed from the viewer’s individual experience. The assemblage operates as a social mirror, reflecting back the construction of bodily fantasy to the viewer; this returns the Mavo discourse to Hegelianism, which suggests that self-awareness is discovered only through the reflection of the self in the Other, in this case the Other being the disobedience of erotic fantasy.[16]

In obstructing the genitals in Kitanai Odani, despite presenting a completely nude body, Murayama denies the containment of the body within a gendered matrix. The sexual and gender projections of the audience cannot be applied, instead the sensuality of the skin dominates and titillates the viewer. The centrality of skin within the photographs, seen undulating in the varying poses, is significant as the skin operates as the mediating surface between the internal and external.[17] Skin can receive, uphold, and represent projections of identity, but it can also be marked by physical experience, making skin a psychosomatic surface. Anzeinu’s theory of skin ego purports that ownership of skin, not just having skin, emancipates the internal self.[18] Since public nudity was pathologized, Murayama’s naked body can be read a proclamation of body ownership beyond reproach of the state. Other Mavo works, such as R.G… (May 1925) (Fig. 5), included altering the familiar appearance of the body through painting onto skin, literalising alterity directly upon a body. In producing an imagined skin, it produces a new framework of bodily introspection for the occupant of the body. Offering a new perspective on bodily belonging, whilst disrupting the surety of the state’s control of the body. Similarly, the intimacy of Murayama’s photographs emphasises skin as a vessel of personal psychological experience, rather than purely as a definable physical body that receives projections of personhood.

The paintings surrounding Murayama in the photographs offer an alternate point of identity recognition beyond the body. The works are physical manifestations of Murayama’s internal perspective that can represent the identity of their maker. By appearing nude in front of their own work, Murayama synthesises the external physical body with the outcome of the internal mind. Murayama wrote on the use of sex and sexuality within art, noting that “sexual potency is the basis of art”, which evokes a personal connection between the presented autoerotic sexualised body and the paintings.[19] For Murayama true creativity is produced through sexual liberation, which is only possible beyond the control of the state. The nudity of the body and the plainness of the setting beyond the paintings removes the external world from interfering with Murayama’s self-representation; the photographs display a world that is entirely inhabited, defined, and constructed by Murayama. The photographs deny the body total authority to define the self; instead, the mind, and products of the mind, are given equal value in the assertion of identity. By interfacing the body and mind within the photographs Murayama visualises a complete self, one that encapsulates Stirner’s construction of the anarchic body, one that is not constructed by or for mankind, but exists as its own unique self: “I do not develop mankind or man, but as I, I develop myself”.[20]

The potency of sexuality endeared it as a tool of social revolution to the Mavo collective, who used it consciously to disrupt the constraints that modern society held upon the body. By documenting, performing, and presenting overt sexuality and transgressive genders Mavo reasserted the primacy of the human body to experience and produce a space of freedom. The movement reconceptualised the body as a mutable object defined by the self. This denied the inscription or projection of state-sanctioned fixed identities onto the individual. Through presenting visually unexpected or ambiguous bodies there is a rejection of assigned subjecthood, as the body cannot be informed by or called forth by another force, it can only be understood or recognised by intimate interaction of the self.

Unfortunately, the radical output by Mavo, though celebrated by contemporary art critics, did not possess the power to overturn or delay the government’s programme of nationalism and militarism. Furthermore, the popularity of anarchism as the anti-state ideology waned. Marxism offered a more cohesive base from which to challenge the state. Mavo, however, with their passion for individualism and freedom from bodily control opposed Marxism due to its anti-individualist tendencies. In 1926, Mavo disbanded. The pressures of police violence as well as government censorship prevented Mavo continuing. The third issue of Mavo magazine (the sale of which was used to fund Mavo activity) was denied distribution rights by the state and therefore made Mavo financially unstable. With the disbandment of Mavo, Murayama shaved off their iconic bob-like hair to mark the end of the movement and published an essay on difficulties of producing radical works within the regime of an authoritarian state.

Though short-lived, Mavo transformed the Japanese art world; eschewing conventional format of hierarchical art production, incorporating interdisciplinary artforms, championing performance and installation work, advocating equality, giving a voice to erased and oppressed identities, and promoting the importance of self-hood within their work, all of which challenged the government’s social matrix and programme of homogeneity.

[1] Gennifer Weisenfeld, Mavo: Japanese Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1905-1931. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 78.

[2] Miriam Silverberg, “Constructing the Japanese Ethnography of Modernity.” The Journal of Asian Studies 51, no. 1 (1992): 50.

[3] The seven editions of Stirner’s The Ego and His Own that were published in Japan between 1900 and 1929 indicate the social importance their philosophy possessed. Lawrence S. Stepelevich, “The Revival of Max Stirner.” Journal of the History of Ideas 35, no. 2 (1974): 324.

[4] The “sound constructors” were instruments made from found objects (oil cans, logs, tin cans etc) that were rubbed together to produce sounds.

[5] Jennifer Robertson, “Theatrical Resistance, Theatres of Restraint: The Takarazuka Revue and the ‘State Theatre’ Movement in Japan.” Anthropological Quarterly 64, no. 4 (1991): 424.

[6] Jay Prosser, Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 37.

[7] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015), 68; see Abraham and Torok’s ‘Theory of Incorporation’; where bodies present prohibited identities to resolve the loss of being named. (“Introjection-Incorporation: Mourning or Melancholia,” in Psychoanalysis in France, ed. Serge Lebovici and Daniel Widlocher (New York: International University Press, 1980), 3-16.)

[8] Jason G. Karlin, Gender and Nation in Meiji Japan: Modernity, Loss, and the Doing of History. (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2014), 232.

[9] Karlin, Gender and Nation, 210.

[10] Weisenfeld, Mavo: 1905-1931, 244.

[11] Satoshi Nomoto, “Jii to Sentan: “Mavo” to sono Shūken” (Masturbation and the Avant-garde: “Mavo” and their Reach, trans. by Joe Nickols (2021)), Ritsumeikan Language and Cultures Research Journal 22 (2011): 54.

[12] Weisenfeld, Mavo: 1905-1931, 243.

[13] Thomas W Laqueur, Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation. (New York: Zone Books, 2004), 361

[14] Though neither Stirner or Hegel directly reference masturbation in their work, the references to bodily enjoyment, autonomy, and participating in actions for the sake of the self suggest that they would not deny autoeroticism as an act of self-discovery. (Lawrence S. Stepelevich, “Max Stirner as Hegelian.” Journal of the History of Ideas 46, no. 4 (1985): 611).

[15] Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (London, UK: Routledge, 1993), 121.

[16] Judith Butler, Undoing Gender. (London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004),147.

[17] Prosser, Second Skins, 72.

[18] Prosser, Second Skins, 73.

[19] In the essay Love and Art History Murayama asserted the centrality of sexual potency within art and that “sex… stands at the beginning of art”. Nomoto, “Masturbation and the Avant-garde,” 53.

[20] Lawrence S. Stepelevich, “Max Stirner as Hegelian.” Journal of the History of Ideas 46, no. 4 (1985): 607.

Joe Nickols

they/them

Joe is an art historian specialising in East Asia, with a particular focus on Japan. Joe’s research mainly engages with queer and gender discourse, particularly focusing on the representation, significance, and development of of Japanese gender construction within society. Joe is also a freelance curator and works closely with contemporary artists.

Instagram: @joenickols

LinkedIn: Joe Nickols

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London

![SOAS History Blog Podcast 11: Poetic Knowledges and West African Histories [Live Recording Event]](https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/soashistoryblog/files/2023/08/Images-of-Africa.-Painting-Tadjo-768x549.jpg)