Why Global Efforts to Address Climate Change Through Forest Conservation are Failing

This blog post is written by Adeniyi Asiyanbi, Senior Teaching Fellow in the Development Studies Department at SOAS. He researches the intersection of environment and development.

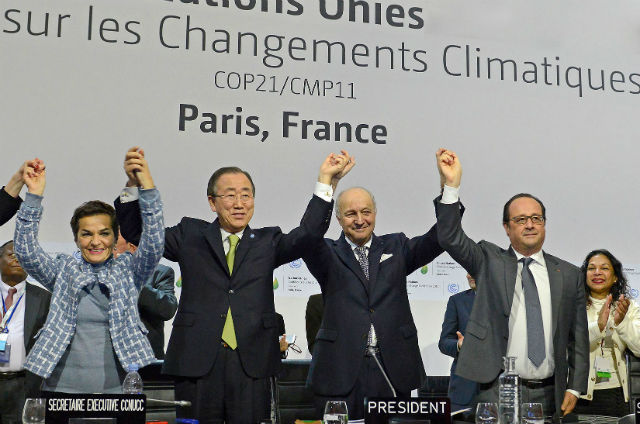

Beneath the euphoria of recent progress in international climate change negotiations in Paris and Marrakech lies the reality that schemes to curb carbon emissions through forest conservation are failing. From the Brazilian Amazon rainforests to the Congo Basin forests, these schemes have not addressed climate change, stemmed deforestation, or improved the livelihoods of forest communities.

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation plus sustainable forest management (or REDD+) is a major global initiative to address climate change. Touted as a means to ‘cheaply’ reduce carbon emissions and drive green growth for both developed countries and developing countries alike, REDD+ aims to reduce global carbon emissions by transferring cash incentives (through grants, credits, and ultimately through the sale of carbon offsets) from developed to developing countries in order to help reduce deforestation in the latter. Global expectations of the scheme are high. The coordinator of the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility declared: it is hoped that REDD+ will “transform rural landscapes, conserve forests, make a difference in climate change trajectories and, most importantly, bring prosperity to the rural poor”.

Yet evidence from our research and that of other researchers shows that these expectations are far from being met. In Nigeria, where REDD+ was adopted in 2010 as a means to protect the country’s last stretch of rainforest and a global biodiversity hotspot in Cross River, our research found that early optimism and expectations have given way to disillusion. Complexities surrounding institutional arrangements, carbon estimation, property rights and forest monitoring have slowed progress. In expectation of a financial reward, and partly in response to global REDD+ requirements, the Cross River State government has replaced the forestry law, halted revenue generation from timber, and imposed a total ban on forest exploitation. Years on, however, the financial reward anticipated by the government and forest communities is yet to materialise. Meanwhile, tensions surrounding REDD+ policies have not only had destabilising effects on government institutions and local forest governance, they have also led to the marginalisation of forest communities and increased deforestation, as documented elsewhere.

Failing expectations

In many REDD+ countries, deforestation is now increasing rather than decreasing, in spite of billions of REDD+ funds being invested in capacity building, institutional restructuring, law enforcement, forest monitoring, among other REDD+ processes. For instance, in the Brazilian Amazon, deforestation has increased steadily since 2014, despite Norway’s US$1 billion REDD+ funds to the country between 2009 and 2015. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa’s flagship REDD+ country, deforestation has increased steadily since 2011, reaching a 14-year peak in 2014. Similar trends are also observable in Cameroon, Ghana, Cote D’Ivoire and Madagascar.

Increasingly, governments are returning to forest-intensive sources of revenue including industrial agriculture, mineral resources, commercial timber concessions, and bogus forest-based infrastructural projects. For instance, the former Cross River State governor lamented in 2015 that “REDD+ is not yielding returns on investment”. His successor recently proposed a bogus 20km wide and 260km long ‘super highway’ through the state’s rainforest, a project that is the focus of local and international campaigns and protests. Like the Nigerian government, many governments have devoted scarce state funds and manpower to implementing REDD+ with the hope of receiving huge green finance. A recent study showed that 84 per cent of sub-national government institutions involved in the REDD+ initiatives studied are putting more into REDD+ than they are getting out.

Tens of thousands of indigenous communities across REDD+ sites have been coerced or sweet-talked into committing to REDD+ based on promises of alternative livelihood support, including regular cash payments. In some cases, governments – sometimes colluding with conservation organisations – have forcibly removed forest communities from their ancestral forest lands in order to create space for REDD+. In East Africa, Nigeria, and Brazil, governments have imposed bans on local forest access while deploying state military and private security with sophisticated surveillance equipment and weapons.

Yet, REDD+ payments and compensations have largely failed to reach many of these forest communities, as recent studies on Uganda, Madagascar, Brazil and cross-country reports by CIFOR also confirm. Disbursed REDD+ funds have been far less than pledged, and much of what has been disbursed has been sunk into capacity building and consultancies facilitated by international REDD+ partners, and international and local NGOs. There is little basis for optimism that things will be radically different in the more advanced stages of REDD+ that promise even greater funding.

An armed police officer setting fire to a local farm shed in Cross River State, Nigeria. Photo credit: ATF, 2013.

So why is REDD+ failing?

When the renowned American Physicist Freeman Dyson declared in a 1977 seminal paper that “the carbon dioxide generated by burning fossil fuels can theoretically be controlled by growing trees”, he was making a theoretical claim. Practically controlling carbon emissions through tree planting and forest conservation is bound to be complex, even messy. The global policy optimism that has propelled REDD+ has not only downplayed the practical complexities of this scheme, but this optimism is itself founded on problematic assumptions, putting REDD+ on shaky grounds from the very start.

Indeed, many of these assumptions do not hold up. Neither the suggestion that reducing global emissions through forest conservation in developing countries is ‘cheap’, nor the claim that REDD+ will achieve win-win outcomes for all involved stand up to empirical scrutiny. Besides, the top-down implementation of REDD+ often only offers a simplistic treatment of complex tropical forest ecosystems and the variety of interactions between people and forests in different landscapes. For instance, assumptions that governments and communities can and will act to stop forest conversion only in response to monetary incentives treat lightly the myriad drivers of and explanations for human-forest interactions – drivers that vary from global economic forces and changing national circumstances to local complexities reflecting different political economies, histories, and cultures.

International REDD+ partners are also sometimes themselves contradictory. For instance, while Norway committed $1billion REDD+ funds to Brazil, it ironically negotiated access to Brazil’s crude oil fields. Furthermore, REDD+ is being pursued through problematic traditional development approaches that are short in life-cycle and as well as top-down, highly technical and consultant-dominated.

So, while policymakers and researchers are coming to terms with the reality of what some researchers have described as just another ‘conservation fad’, the world needs more nuanced and contextually-appropriate responses to the complex socio-environmental challenges of our time.

Great insight. Thank you for sharing. In my my perspective, scholars should invest more in research and innovation and this should also be supported by relevant stakeholders in terms of funding.