SOAS History Blog Podcast, Ep. 4: The Ramayana – History as Storytelling, Storytelling as History

More about this

Dr Anandi Rao

Interviewee

she/her

Lecturer in South Asian Studies, SOAS University of London

Dr Roy Fischel

Interviewee

he/him

UG Research/ISP Tutor (History), SOAS University of London

Dr Richard Williams

Interviewee

he/him

Senior Lecturer in Music and South Asian Studies, SOAS University of London

Alexa King

Guest Podcast Producer

Alexa is currently pursuing an MA in History with Intensive Arabic at SOAS University of London. They graduated from New York University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Drama, and are interested in performance cultures in the Middle East.

LinkedIn: Alexa King

Dr Eleanor Newbigin

Interviewee

she/her

Senior Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia, SOAS University of London

Haritha Balasubramaniyan

Interviewer/Transcriber/Blog Editor (2021-22)

she/her

Hello! I’m Haritha and I’m currently pursuing an undergraduate degree in Global Liberal Arts. Academically, I focus on History and Politics and am currently involved with the SOAS History Society as well. Apart from that, I spend my time exploring classical Indian forms of artistic expression, focusing on Bharathnatyam and Carnatic music. Another ‘project’ of mine is learning languages from different linguistic schools. Apart from Tamil, my mother-tongue, and English, I have learnt Hindi and am currently learning Arabic at SOAS. Through my involvement with the SOAS History Blog, I hope to broaden my understanding of the discipline, while contributing to its decolonial vision.

Samples of music in this podcast have been for research and academic discussion only.

Transcription Part I: The Ramayana

Music in Part I: Sita in Panchavati by Sadhana Sargam the anime film The Legend of Prince Rama (1992)

Haritha: The following summary of the Ramayan’s key plot points was intended to provide the audience at the event ‘History as Storytelling and Storytelling as History’ with crucial context necessary to understanding the panel discussion. This summary was synthesised from my own encounters with multiple forms of the Ramayan text – childhood stories, religious traditions and festivals that I grew up celebrating, cartoons, novels, TV shows, movies, and indeed, a more academic engagement with Paula Richman, Volga, and AK Ramanujan who have engaged and commented upon this rich tradition. The telling itself reflects the contemporary location of what forms the skeletal timeline of the epic that is presented here, quite isolated from the deeply religious sense of reverence that surrounds the epic. Because (of) the complexity surrounding the epic, its many forms, as well as discourse surrounding it and its many engagements, it is impossible to summarise within the scope of this simple summary. This complexity is highlighted and discussed in the panel discussion.

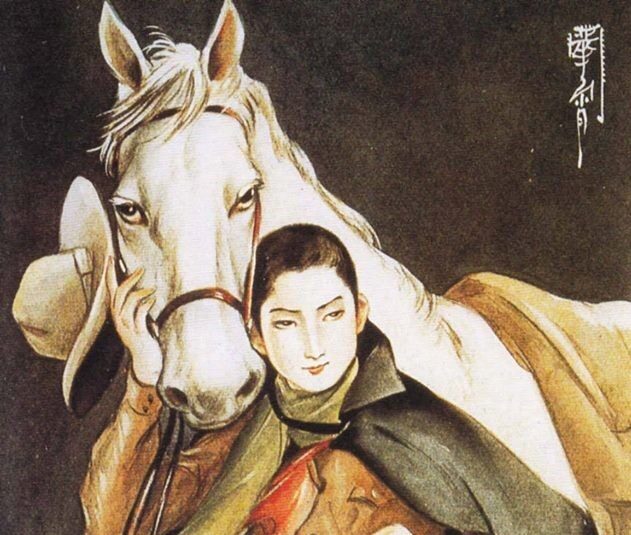

Haritha: When the story starts, you have King Dasarath who is known to be magnanimous and has three wives, but for the longest time, he did not have any heirs. Through the interventions of sages and gods, he is bestowed with four sons. As the story progresses, because of the politics of succession, king Dasarath is forced to send his son Ram into exile to a forest for fourteen years. All of this is over succession because one of the wives wants her son to be ruler. In the next image, we can see Lord Ram in the forest and his wife Sita, who ardently follows her husband into the forest, renouncing her wealth and royal status. The third person in the picture is Lakshmana, one of Ram’s brothers who is loyal and devoted to him and follows him into the forest. What happens next is that Ravana – the villain of our story and ruler of Lanka, abducts Sita by tricking Ram and Laksman into leaving her alone in the forest in the hut they live in. He abducts her in a flying chariot and gets her to Sri Lanka. Sita refuses to live in the palace because of notions of purity and [a] monogamous sense of ‘not being in another man’s threshold or household’. Hanuman, who is an anthropomorphised image, and his community of people build a bridge from India to Sri Lanka and helps Ram’s army get there. Here, an epic showdown occurs. There is a huge war, and at its end, Ram – the good guy, wins.

You’d think they’d live happily ever after, but no. They return to the capital Ayodhya, where Lord Ram and Sita are coronated and claim their rightful throne. But people began raising suspicions about Sita, saying “she was in another man’s house for a whole year, that doesn’t seem right.” In some versions of the tale, Sita is then forced to go through a trial-by-fire, in other versions, she does so willingly as a testimony to her righteousness. She emerges unscorched and becomes queen. In many versions, the tale ends there. In other versions, doubts surrounding Sita’s fidelity persist despite her trial-by-fire, causing her to resign from royal life to the forest. In other tales, she is forced to do so whilst pregnant with Ram’s twins – Lav and Khush. Despite her living in the forest as a hermit, Lav and Khush become crowned as Princes through various coincidences where they run into Lord Ram’s royal horse. And so, they continue the lineage of Lord Ram.

That is the most simplistic possible version [of Ramayan].

Transcription Part II: History as Storytelling and Storytelling as History

Alexa: This is a SOAS History Blog podcast. In this instalment, we bring you an excerpt from the SOAS History Blog event ‘History as Storytelling, Storytelling as History – The Ramayana.’ This virtual event [hosted via Zoom 27 January 2022] was presented by Haritha Balasubramaniyan and our panellists were Dr Anandi Rao, Dr Roy Fischel, Dr Richard Williams, and Dr Eleanor Newbigin. If you’d like to hear Haritha’s summary of the epic, you can find an audio recording at blogs.soas.ac.uk/soashistoryblog. Most of the panel’s discussion was focused on the multiple versions of the Rayamana that exist, and how these different tellings have been used politically throughout history. We begin with Dr Williams.

Dr Richard Williams: For me, when I came into this panel, like many people, I was thinking in terms of AK Ramanujan’s essay ‘Three Hundred Ramayans’ where he talks about the diversity, spread, different tellings, and the sheer variety that you get within this tradition. He makes the point that no one ever reads the Ramayan or the Mahabharat for the first time – the stories are always there. There is no ur-text. You have some aspects of it in your cultural repertoire from the get-go. My point here is that we have these core texts and core versions, but we also have the splinters and branches. [These are] tiny fragments that develop a life of their own. What’s quite interesting is sometimes, it is about the story. Often, when we think about the histories that revolve around the Ramayan, we focus on the content and message, and how a message can be politicised and how a message can speak to debates that are happening in all these different settings.

Alexa: The panellists then tackled the question posed by Haritha – in what ways is the search for one definitive Ramayana problematic? How can the existence of multiple Ramayanas be conceptualised in academic spaces? The conversation begins with Dr Williams, followed by Dr Rao, then Dr Fischel, and ending with Dr Newbigin.

Dr Williams: Part of the challenge that I think we have is figuring out what interests us, and often that will bias how we view the entire set. I think we do gravitate towards the ones that are different – the ones that stand out for some reason. We have to be cautious as we approach it as historians now because we might go looking for the things that have a unique selling point – something that might sound exciting and dramatic when actually, that’s not the point of retelling it again and again. It’s about having a specific flavour, nuance, or simply relishing this depth of things that people already know.

Dr Rao: What interests me is the political [aspect] and how Ramayan is used in political ways. There are two things about Ramanujan’s essay that is interesting to me. One is this idea of a ‘telling’ and I’m interested in how to think about a ‘telling’ without using an original and implications to how we conceptualise and think of translation or multiplicities in retellings and reiterations. What is interesting about Ramanujan’s essay is the fact that it caused such a furor when it was added to the Delhi University curriculum, and the ways in which this idea of multiplicity is somehow destabilising notions of history. So I would be curious about thinking about the Ramayana and issues of nationhood in different periods like the Early Modern and colonial through a legal-historical lens.

Dr Fischel: Anandi, you have raised the political issue and imagining group identity Self and Other. This, I guess, is one of the advantages – the fact that there is a story so familiar to so many people at the same time that only resonating one bit or section will bring such a rich world of imagery that has been an incredible political tool for different rulers in different settings throughout the history of South Asia. I find most fascinating, the incarnations of the Ramayana in how it was used in the Early Modern period in the Deccan region of South India.

In the empire of Vijayanagara in the fifteenth century, following the argument presented by Sheldon Pollock, the Ramayana became an important tool of redefining kingship in a very certain way within a certain political setting of Vijayanagara fighting against the northern neighbours who were ruled by Muslims. It is a clear introduction of this element into the story and the way that they did it is fascinating. We see pouring in so many directions to redefine what kingship is. Now, they started calling certain hills or certain sites around the capital city with names identified with the Ramayana. Later, they introduce a very important festival in the court (so it’s a known holiday), the Mahanavami. It is the autumnal festival on the last day of Dusshera that was turned into a very important political event in which there is a ceremony where publicly, the King is becoming Rama. It became such a powerful tool that it was cited directly afterwards in many southern courts. The quirk here is that we can see how it developed a life of its own in a way much like the Ramayana itself, with its many retellings in different contexts. Some of the courts ruled by Muslim rulers continued to celebrate Mahanavami as a central event for manifesting royal power. So even though it started, according to one interpretation, within the context of fighting against Muslims as a way to define the King as the defender of Dharma or religious duties, it became so powerful that it was copied into Muslim courts. We see that the epic itself had so much power in shaping language that afterwards it became almost synonymous with royal power in India that it had to be replicated within and without this context throughout.

Dr Newbigin: It has been about this change in form – not just the story itself, but also its form, as Richard said. The way in which it is performed is itself connected to power. I’m sure many of you know the way in which the Ramayana is politicised with one of the major debates around it being, as Andandi referred, growing restrictions on duplication and growing insistence on a single Ramayana which itself, is a practice that has a history in the colonial state and ideas about narrative and authority. It has taken on particular dimensions in the last thirty years – in 2017, a case was moved to the Supreme Court in India where Lord Ram himself was a legal plaintiff, making claim to the site of the Babri Masjid mosque in Ayodhya as his birthplace. What’s interesting about the case is that it used, what in many conventions are seen to be historical forms of evidence. So testimony or evidence-writing from European visitors to Ayodhya in the 18th century was presented as evidence of the fact that this was the site of Ram’s birthplace. Archeological forensic material was also used as part of making this case. So this move away from the form that other colleagues have spoken about – the celebration of multiplicity, the fact that you can have an ur-text and deviate from it, you can have a performer bringing their particular individual take to the performance; you have the opposite happening in this legal case. There’s an attempt to convince down and concretise these sets of claims around documents and ‘artefacts’ in the name of a particular understanding of the historical hereto. In one sense, a notion of the historical is absent of historiography. The Ramayana can still be performed as a sort of cultural piece, but there is an attempt to police its role in the state – not as multiplicity, but as something that has a very concrete and physical form.

Alexa: The convversation then pivoted slightly from the existence of multiple versions of the Ramayana to a discussion of how and by whom the Ramayana could be interpreted and for what means. We start with Dr Newbigin.

Dr Newbigin: There has been a movement of feminist writers going back and uncovering older versions of the Ramayana in response to this attempt to create a single historical narrative of Ram’s life through the Ayodhya campaign. Scholars who are interested in the historical are responding to that by pointing to deviation, multiplicity, and the fact that there are Ayodhyas across the region. ‘How do we know that this Ayodhya is the one?’ [They are] questioning the authority [of the single historical narrative].

Dr Fischel: We have seen attempts in recent years to look at the Ramayana and Mahabharata as historical sources by certain groups to say “this is actually a clear depiction of history”. I wonder if this has another impact. To create more of a shared version of this story that is becoming an ur-text by itself and reading the Ramayana as historical truth and trying to think about them as a way to construct a past – is this not part of yet another attempt to create one authoritative version of the story because history, the way that it is described, used or created here, is a Western intellectual tool. It does not like multiplicity about the past. So I wonder if we will see this kind of change following this new-ish historical approach to the epic.

Dr Newbigin: That’s one of the things that’s interesting – you now have this historical reading of the Ramayana that is disputed by professional historians. But if we’re going to go back to the question of ‘what is the narrative form of history writing?’, this is a great situation to think about and see how it changes.

Dr Fischel: When we are talking about the multiplicity of the Ramayana, are we talking about the many versions across South and South-East Asia? Is it a contemporaneous multiplicity of versions across class, time, and space?

Dr Williams: To me, it’s two things – the fact that there are lots and lots of versions and texts. But also that there are different accents and points of emphasis. So the idea of ‘what is the point of Ramayan in a sentence?’ often changes. I think this is why there is so much anxiety now about the fact that there are multiple versions because there is a particular image, sense, and flavour about what the story is about. So if you bring in alternative flavours, then there is anxiety around that.

Dr Rao: Caste, class, gender, race – all of those come in.

Dr Newbigin: The multiplicity is also the political power of this work. The Ramayana is powerful because it seems to bring people together across this vast subcontinent because it can cope with difference. I think this politics of policing dominant narratives is the norm because it focuses on a very particular understanding of patriarchy, masculinity, gender, and caste here too as Anandi as said. So there’s been a long project of policing these texts and prioritising, if not versions, then certain norms and conventions.

Dr Fischel: We have the famous issue of the seventh book – what’s going on with Sita after the end of many of the events? [The issue is that] it is deliberately omitted in many versions, including some of the classical versions. The front thing we are talking about is a very old one; the multiplicity historically, is not always harmonious. It is not only a modern thing of trying to systematise, it is as old as the epic, I suspect.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London