The Father and the Assassin – Review

By Amrita Shodhan, Sr Teaching Fellow, Department of History, SOAS.

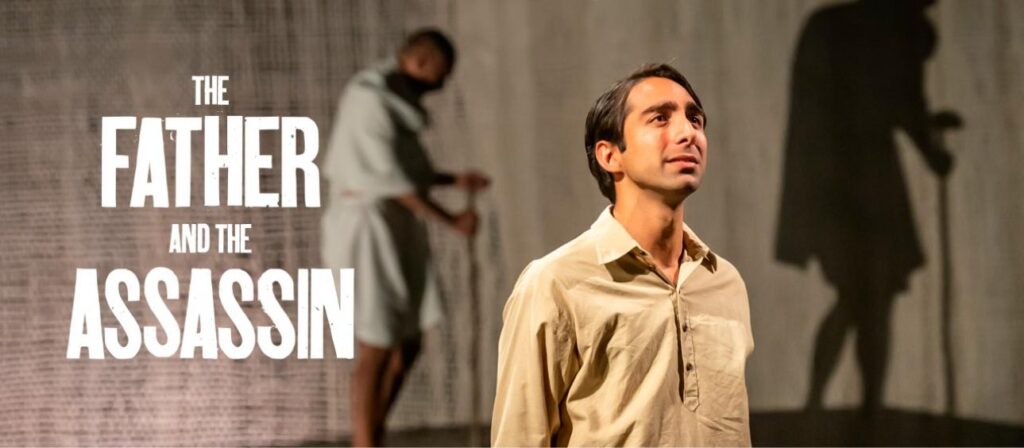

The Father and the Assassin – written by Anupama Chandrashekhar directed by Indhu Rubasingham and acted by Shubham Saraf with others including Ayesha Dharkar opened on the massive revolving stage of the Olivier at the National Theatre to rave reviews from across the press spectrum from The Guardian to Time Out . Presented as an investigation into the life of Gandhi’s assassin, the play falls short of an empathetic psychological portrait.

I must admit that with my Gandhian sympathies, I was afraid to see the play, fearing to endorse the rousing Hindutva support for Godse. However, there was no denying my extreme curiosity about the play and its take on the assassination. Finally, a week before the play’s closing, I picked up the courage to see it. The house was packed with not a seat remaining and I felt at home with the racial mix in the audience, reflecting the mix amongst the actors. Shubham Sarraf opened the play with an intimate conversation with his post-colonial, post-Brexit audience, effortlessly combining his role as narrator and protagonist. I was now open to empathising with the oppressed child searching for and revenging himself on a father figure, as analysed by Ashish Nandy (2015, 1990 [1980]).

Saraf begins the narrative by talking of Godse’s childhood, progressing to age 11, when he recognises himself as male. At this point Anupama stages a fictional encounter with Gandhi, the play’s dialogue becomes explicitly political. The usual arguments about Gandhi’s responsibility for partition and the horrors of independence take over. The play write speaks to the current right-wing mood in India and plays to their complaints about Gandhi, using them and leaning on Godse’s own justifications presented as his court room speech. Both hold Gandhi responsible for the ills of partition and justifying his murder to assuage the ‘Hurt’. The play relies on a good mix of fictionalised facts to suggest conversations with Gandhi and other Gandhians. However, they remain on the surface of Gandhism and cannot lead us to an in-depth political conversation nor an in-depth psychological conversation. The play was a sad missed opportunity to complicate the assassination and humanise the person of Nathu/Nathuram. Instead the rising of Godse’s own self-glorifying persona panders to the current political dispensation without upsetting differing political convictions. One must congratulate the National Theatre for inserting themselves into the Indian political scene and boldly stepping up to a post-colonial role for British theatre.

References:

Nandy, Ashis. 2010. “Coming Home: Religion, Mass Violence, and the Exiled and Secret Selves of a Citizen-Killer.” Public Culture 22 (1): 127–47. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=bas&AN=BAS492991&site=eds-live.

Nandy, Ashish. 1990. “The Final Encounter: The politics of the Assassination of Gandhi”, in At the edge of psychology: Essays in politics and culture (Paperback edition.) Delhi ; Oxford: Oxford University Press.