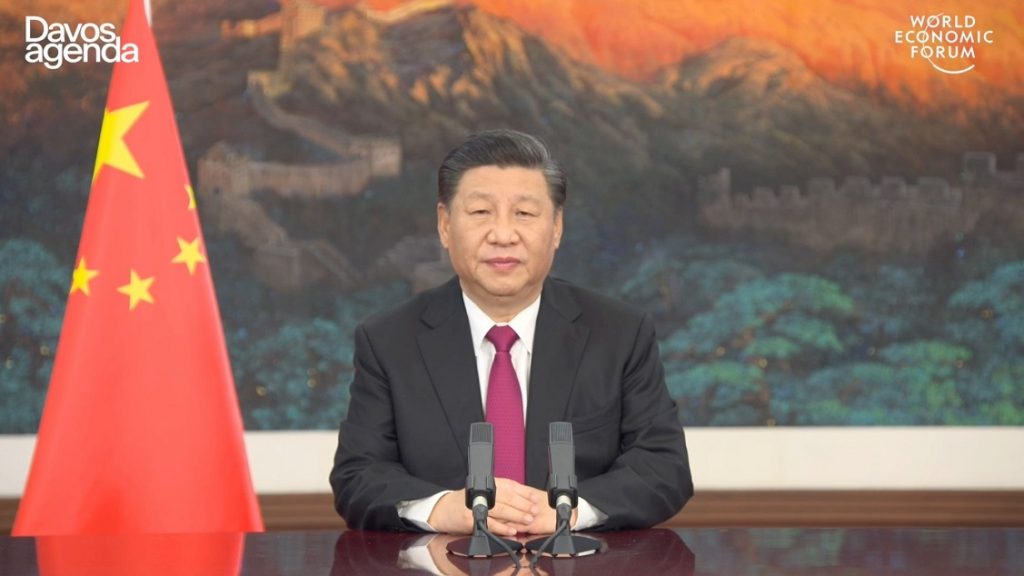

Mr. Xi zooms into Davos

By George Magnus | 28 January 2021

Two veteran China watchers comment on Xi Jinping’s keynote address to The Davos Agenda 2021 | World Economic Forum. This is part one. Read part two here.

Davos, with the theme this year of Rebuilding Trust, was diminished as an event, perhaps also as a concept. The curtain-raiser was the keynote address by Chinese President Xi Jinping on multilateralism, openness and inclusivity in a fractious, pandemic world.

The audience was invisible. The applause, if there was any, was silent. Like 2017, though, there was still fawning, this time as World Economic Forum founder, Klaus Schwab, bookended Xi’s address, thanking him at the end for reminding that we are ‘all part of a community with a shared future for humanity’. Not quite Xi Jinping verbatim, but close enough. Yet, what did Xi Jinping say that was noteworthy, and perhaps as importantly, what didn’t he say that we should note?

Xi talked about the inevitable and widely shared goal of working together to conquer the pandemic and tackle climate change. There was of course, no mention of accountability or responsibility for the outbreak of the pandemic, or a thorough investigation to be shared, which might have got a ‘rebuilding trust’ checkmark. None either of the ways in which China has tried to blame the US, Italy, the UK and even the import of frozen foods, for Covid19, and unleash so-called ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy, designed to accuse, bully and ridicule other countries suffering from the pandemic.

Xi’s speeches often embrace many platitudes, and flowery language that sometimes comes across as a corporate marketing brochure. The language can be quite disarming but it is used with great care to send clear, but sometimes, covert messages.

Message to the Global South

Xi made a familiar overture about the need to close the equality gap between emerging and advanced nations, and give the former more resources and a bigger say in global governance. There was an implicit message here that China, not the West, would champion their cause, but no mention of the fact that Chinese help is contingent on non-critical support for its and the party’s global narratives. The US and its allies, though, should take note.

Referring to openness and inclusivity, Xi indulged in a little martial arts to turn these liberal democratic exhortations against their liberal nation state protagonists, in view of the charges of protectionism, immigration curbs, and now ‘vaccine nationalism’. While it is true that China has used the pandemic to provide public health goods and vaccines to many countries, President Xi did not acknowledge that openness and inclusivity are not typically associated with China, and certainly not for migrants either from abroad or the 280 million from its own countryside who work in towns and cities.

President Xi said China will ‘further deepen South-South co-operation’, building the proverbial ‘community’ of nations which chooses to align within China’s political and economic orbit. Yet, many that have done so under the Belt and Road Initiative have pushed back against over-indebtedness to China, and poor project governance and competence.

Message to the US and liberal democracies

The message to the incoming Biden Administration and its allies was essentially a lecture about the need to uphold multilateralism, avoid ideological prejudice and division, and beware a new Cold War. Yet, as President Xi worked his way through the tasks the world must accomplish, it was hard not to see the disconnect between the message and the orator.

On macroeconomic policy co-ordination, he urged a ‘shift in the driving forces and growth models of the global economy’, but neglected to say that China, itself, was a laggard in this respect, and that the impetus for market-oriented reform and openness had run aground in 2015-16 and had, if anything, faded even further since for political and ideological reasons.

He stressed the need to abandon ideological prejudice, secure ‘win-win’ cooperation, and recognise that no country is superior to any other. Yet, he failed to acknowledge his own role in nurturing China’s long-term ideological struggle with the US and the West, in which socialism would emerge victorious over capitalism. He didn’t refer the formal rejection of western, liberal values and beliefs authorised in 2013. He didn’t say that China’s rhetoric , especially during the pandemic, has regularly asserted China’s superiority.

A delicately crafted passage on diversity, tolerance, and other benign attributes of peaceful coexistence didn’t refer the treatment of the Uighur people, which has attracted the term ‘genocide’ as defined under the United Nations Genocide Convention; nor, the abrogation of the 1997 handover agreement and harsh crackdown in Hong Kong under the new National Security Law. Both figure prominently in a catalogue of human rights and legal abuses, and extra-judicial punishments.

In a prominent section at the start of the 4 recommendations about how to uphold multilateralism, Xi says “to start a new Cold War, to reject, threaten, or intimidate others, to wilfully impose decoupling, supply disruption or sanctions, and to create isolation or estrangement, will only push the world into division and even confrontation”. He should know.

He might have been biting his tongue as he uttered these words, because he has undertaken all of these acts. Truculence in international relations has been a hallmark of Xi’s China for a few years now, and China has been no slouch when it comes to using commerce and trade as punishments, notably recently in the case of Australia. Indeed, the term coercive diplomacy has entered our language specifically to describe China’s actions of bullying and intimidation with regard to a slew of countries, including also Taiwan, India, and other countries in the Indo-Pacific and around the South China Sea, and in Europe. Interference, as opposed to the peddling of influence, in the domestic affairs and political processes of other countries is a common complaint.

China has been practicing selective decoupling for years in industrial policy, technology policies and the application of standards. There are now increased sensitivities about national security in the technology and other sectors everywhere, and new vulnerabilities to single source suppliers in key goods. China is no different. Its own self-reliance strategy for science and technology, angst about supply chains, and new focus on so-called Dual Circulation Strategy all speak to Chinese decoupling by other names.

Within a day or so of President Biden’s inauguration, moreover, and in a veiled threat to his team, China announced travel, financial and ‘future business’ sanctions against 28 Trump administration members and their families for ‘anti-China’ actions and rhetoric. It quickly publicised several fighter aircraft and large bomber sorties through Taiwanese airspace in the latest instance of bullying what China calls the ‘renegade province’.

Xi Jinping’s championing of globalisation at Davos in 2017 was a good bit of opportunism that lacked real substance. China isn’t and cannot be a globalisation leader. The pitch this week for ‘win-win multilateralism’ based around China’s global role, having seemingly conquered Covid, should be seen in the same way. The veiled criticisms at the US and others just remind us that people who live in glass houses should not throw stones.

Authoritarian control, the demand for compliance, and the suppression of debate have helped China manage a serious public health crisis, but they do not offer the world a helpful template to live and thrive.

George Magnus is a Research Associate at the SOAS China Institute and at the China Centre, Oxford University. He is the author of Red Flags: Why Xi Jinping’s China is in Jeopardy (Yale University Press, 2018).

The views expressed on this blog are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the SOAS China Institute.

SHARE THIS POST