Speaker’s Corner: Researcher at the Princes School of Traditional Arts, Bilal Badat, explores when and why depictions of Prophet Mohamed become incendiary

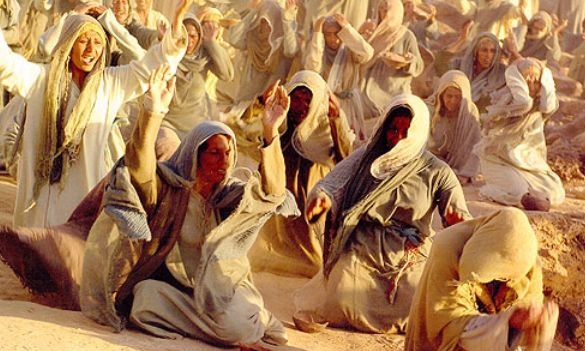

Image drawn from “Muhammad: The Messenger of God”, a 2015 film by Iranian director Majid Majidi.

Researcher at the Princes School of Traditional Arts, Bilal Badat, asks when and why depictions of Prophet Mohamed become controversial?

From caricatures to carbon dated Qur’ans, 2015 has been a busy year for critics and commentators of the Prophet Muhammad. It began with the attack at the headquarters of Charlie Hebdo where two gunmen killed eleven staff members and one police officer. Their principle motivation was described as revenge against the cartoonists and employees for a number of controversial cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad published previously by the French satirical magazine. In the months that followed commentary as to the nature of the cartoons, the notion of free speech, and Islam’s relationship with the Prophet Muhammad filled the airwaves.

In response to the shootings several art historians shone a spotlight on some of the diverse traditions of depicting the Prophet Muhammad throughout Islamic history. Their general argument held that Muslims in the past were not averse to drawing representations of the Prophet and that contemporary reactions against such drawings are ignorant of Islam’s own civilizational heritage. Any similarities that can be drawn however between Islamic paintings of the Prophet and the Charlie Hebdo cartoons begin and end with the formal act of depiction. On the one hand we have highly circumstantial paintings of the Prophet painted by trained Muslim craftsman for the attention of a very limited number of wealthy Muslim patrons. On the other are highly provocative images drafted by French cartoonists intended for public dissemination within a society already beset with economic disparity and racial tension. In this comparison at least, the shared subject of the image clearly disguises a host of differences.

The different responses amongst Muslims to both sets of images would also suggest that Muslims make a clear distinction between Islamic paintings of the Prophet and the Charlie Hebdo depictions. Whereas the former images were considered as acceptable methods of depicting the Prophet (albeit within the socio-cultural context of the image’s production) the Charlie Hebdo cartoons are the complete opposite. When exploring the roots of Muslim indignation at the Charlie Hebdo cartoons the question we should be asking is not whether images of the Prophet are acceptable or not, but rather why one method of depicting the Prophet is more acceptable than the other.

Although a truism it is worth repeating that when it comes to the act of depiction no painting can fully mirror its subject. As with any historical reconstruction therefore there is a tremendous gulf that exists between how someone actually looked in real life against how that person was depicted on paper or canvas. Jesus may not have been blonde with blue-eyes and it is debatable whether Socrates had bulging biceps and a glistening six-pack (see Jacques Louis David’s 18th century painting ‘The Death of Socrates’ for an example). In between depiction and its subject therefore there exists a whole host of ideological, cultural, political, economic and religious determining factors which are mediated through the artist and contribute to the creation of an image at any given moment throughout history.

But that is not all. Just as these contextual factors transform the nature of the image, so too do they transform the nature of the depicted. Take the Charlie Hebdo cartoons for example. Not only do Muslims disassociate from the sinister looking hook-nosed Prophet depicted in the cartoons but they also fail to recognise the war-mongering Prophet the cartoon tries to represent. It is not so much the image that concerns Muslims as much as the perversion of the subject that the image is representing. The rejection of misrepresentation is equally vehement even if the ‘authors’ themselves claim to follow the Prophet. Muslims are similarly mystified when ISIS manipulate the Prophet Muhammad’s character to sanction torture and mass execution. As with the Charlie Hebdo cartoons, the political factors mediating ISIS’ approach have seemingly transformed the Prophet into a wholly fictitious character whose identity runs counter to the peace loving Prophet most Muslims around the world identify with.

The crux of the issue is thus one of representation. Muslims are insulted by Charlie Hebdo for the same reasons that they are offended by ISIS: both of their depictions misrepresent the character, honour, and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. In fact, one could even argue that contemporary depictions of the Prophet in the media cannot even be considered to be variant interpretations of the same man, but rather parallel interpretations of different historical characters all grouped under the singular title of the Prophet Muhammad.

As the recent biopic of the Prophet from the renowned Iranian director Majid Majidi has shown, Muslim approaches to representing the Prophet Muhammad are still as diverse and engaging as the number of ways he was depicted throughout Islamic history. Negative reactions amongst Muslims to cartoons are thus predicated upon something more profound than religious aversion to figural imagery. Let us therefore look beyond the cartoons and images and fully contextualise Muslim indignation by exploring some of the sinister motives navigating the boundaries between the act of depiction and the misrepresentation of its subject.

Bilal Badat is a researcher at the Princes School of Traditional Arts and is currently completing his doctoral thesis on pedagogy and aesthetics in Ottoman calligraphy.