How Speculation Contributed to Two World Food Crises

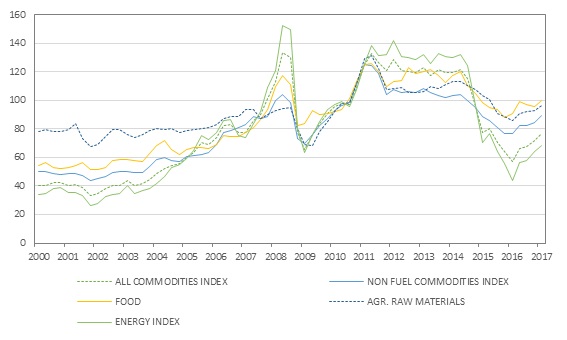

The hypothesis that financial speculation was behind soaring food prices in 2007-08 and 2010-11, or at least substantially contributed to it, first surfaced in 2008 when ‘The Accidental Hunt Brothers’ Report by Masters and White (2008) drew a link between institutional investors’ positions in commodity futures markets and the significant and synchronised spike of commodity prices. Prices across commodities almost quadrupled between 2004 and 2008, including prices of key staples such as wheat, corn and soybeans; see Figure 1. These price developments threatened food security in food import dependent regions and are widely recognised for having contributed to economic and political instability, hitting hard the livelihoods of the poorest; see From Bread Riots to Obesity by Jane Harrigan. The suggested link between financial speculation and soaring food prices by Masters and White (2008) was reiterated by a staff report of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the United States Senate in 2009 and the UNCTAD Trade and Development Report of the same year, which was published under the heading ‘The Financialisation of Commodity Markets’. An OECD report, authored by the two Illinois-based US economists Irwin and Sanders (2009), claimed, on the contrary, that the growing presence of institutional investors in commodity futures markets had not contributed to higher price levels or volatilities and, if anything, had reduced volatilities by contributing to market liquid.

Figure 1. Commodity Price Indices (indices of market price and unit values)

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics.

The controversy marked the beginning of a heated debate in both the political and academic realm around the ‘financialisation hypothesis’, namely the hypothesis that speculation – broadly defined as any position taken in the derivative market without the intention to manage price risk stemming from the future acquisition or sale of a physical commodity – contributed to excessive price levels, volatilities and co-movements. Excessive in this context is understood as price dynamics in excess of what could be justified by market fundamentals, i.e. demand and supply factors. Speculative bubbles in commodity markets are no new phenomenon; see Maizels (1987). However, what is new to the debate is the complexity of instruments at the disposal of speculators and the multiplicity of actors involved in commodity derivative trading. The term ‘speculator’ now subsumes a myriad of investors with different interests, including institutional investors such as pension funds, hedge fund, and high frequency traders. For analytical purposes, the academic literature distinguishes between active and passive investors, whereby the active category is further subdivided into informed and uninformed investors. It is the passive investor category, including mostly institutional investors that replicate broad based commodity indices as a portfolio diversification tool and hedge against inflation, that has attracted most attention in the financialisation debate; see Nissanke (2012) and Mayer (2012).

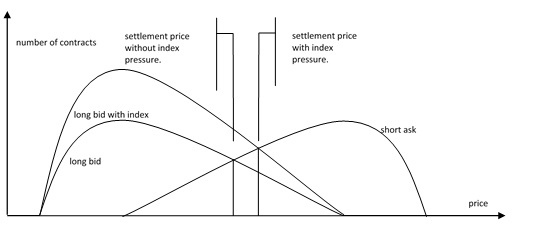

Investors that wish to gain exposure to a particular commodity index replicate the index by allocating a share of the total amount they wish to invest into each commodity that is listed in the index. The share by which each commodity contributes to the index differs across indices and is re-evaluated regularly. The reason why the increasing popularity of commodity indices attracted the attention of practitioners and policy markets alike is twofold. First, through index investment, large sums of money are channelled into commodity futures markets whereby index traders’ position taking is unrelated to a commodity’s fundamentals. Index traders do not react to demand and supply conditions in the commodity markets they are investing in and hence induce price impulses that are unrelated to any ‘real’ market conditions. Second, index traders are overwhelmingly long in the market, meaning, they hold ‘buy’ positions thereby putting upward pressure on the price of the futures contract they are investing in if not enough short traders are willing to enter as counterparty at the going price; see Figure 2. Further, index traders often seek long term exposure to commodities. When the contract they are investing in expires, positions are rolled over. This ‘index roll’ is largely synchronised. Therefore, with the entrance of index traders, a bulk of synchronised positions enters commodity futures markets whereby the information content of these positions is negligible with regards to market fundamentals.

Figure 2. Book Effect of Index Traders

Since 2008, several studies have attempted to empirically establish a link between price levels, volatilities or co-movements and index trader positions. For this purpose, most studies rely on position data for US commodity futures markets that is published by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and disaggregates long (buy) and short (sell) positions by trader type: commercial hedgers, non-commercial non-index traders, index traders, money managers, swap dealers and others. The data has several shortcomings but remains the best available measure for trader activity; see Irwin and Sanders (2011) for a discussion. The dominant method that has been used to empirically evaluate the ‘financialisation hypothesis’ based on trader position data is the Granger non-causality test. The test evaluates statistically the relationship between past changes in position data and price changes or changes in price volatility measures. Most studies that use such tests fail to establish a significant (reliable) link between trader positions and price levels or volatilities.

This dominant empirical method is problematic on two grounds. (1) Prices set at financial exchanges move fast, while trader position data is collected weekly for each Tuesday. The time lag underlying the Granger non-causality framework hence implies that position changes of the previous week drive price changes of the current week. The distance between these changes is too far to be meaningful in a financial market context. (2) Commodity price series are volatile and driven by a multitude of factors including market fundamentals as well as noise. Any test on the link between trader positions and price movements has to take into consideration fundamental factors. However, the extent to which a price series moves against its fundamental value is difficult to identify as measures of fundamental variables are often latent or unavailable.

Given the shortcomings of the dominant empirical method, an arguably better approach to testing the financialisation hypothesis is an empirical evaluation based on the difference between two commodity price series, as, for instance, the futures price and its underlying spot price, or price series of futures contracts with different maturity dates. Since these pairs of price series or spreads are driven by the same commodity-specific fundamentals, the difference in level and variability can be attributed to the different composition of traders in the particular market or contract (plus cost of storage). Unfortunately, empirical studies have widely neglected spread analysis, with some notable exceptions published in recent years. A quick look at papers that summarise the empirical evidence – e.g. Irwin (2013), Fattouh et al. (2013) and Cheng and Xiong (2014) – proofs the point of a dominance of the price level and volatility analysis over the spread analysis. Only 20 per cent of the reviewed studies consider price spreads, whereby studies that consider price spreads report evidence in favour of the financialisation hypothesis twice as often than papers that focus on price levels and volatilities only.

In two recent papers How financial investment distorts food prices: Evidence from US grain markets and Too Much of a Good Thing? Speculative Effects on Commodity Futures Curves, I exploit the insight that price spreads provide a more fertile ground for testing the financialisation hypothesis. As mentioned earlier, price spreads are usually governed by simple arbitrage relationships either between simultaneously traded contracts or derivatives (such as futures) and the physical markets. In an ideal world without market friction and transaction costs, arbitrage is perfect, aligning prices. However, in most cases arbitrage is imperfect, due to transaction costs, lack of information or price rigidities. I hypothesise that the slower arbitrage is, the more visible the effect of speculation becomes. Index traders are only active in commodity futures markets but do not hold physical positions (in most cases). Therefore, the price effect originating from index traders’ position taking should only be visible in the futures price but not in the spot price with the spot price being equivalent to the price payable for the physical commodity. In the case of the spread of between two futures contracts, any effect originating from index traders’ position taking should be most strongly visible in the contract in which most index traders are investing. The size of the spread between spot and futures or futures with different maturity dates that cannot be explained by costs of storage (the simple arbitrage relationship) can then be linked to price pressure effects induced by index traders.

An episode of convergence failure between futures and spot prices in US grain markets due to problems originating from the storage and delivery system of the Chicago Board of Trade between 2005 and 2010 offers a perfect case for testing the above hypothesis. Based on a simple price pressure-augmented commodity storage model that incorporates factors that have caused limits to arbitrage and hence facilitated non-convergence in the first place, I theoretically and empirically show that the extend of the spread between futures and spot prices during this episode of convergence failure is explained by index pressure effects. These effects are found significant for wheat, corn and soybeans markets. I find similar effects for the spread between different futures contracts for cocoa, coffee and cotton markets in the second paper.

These results have important implications for the financialisation hypothesis. Index pressure effects on prices can be substantial. These effects are concealed in most times when arbitrage is effective and spot and futures prices align. The question then becomes whether spot prices align with futures prices or futures align with spot prices. In the latter case, the index pressure effect is transitory. In the former, the price effect spills over to the spot prices with consequences for the overall price level. Arbitrage theory does not help understand the direction of the adjustment, however a closer look at the institutional structure of commodity markets might. For many commodities, including food commodities, contracts involving the exchange of the physical commodity take the futures prices as a reference price. This is partly due to convenience, but primarily to ensure hedging effectiveness. For hedging to be effective, the price agreed for the physical exchange must be identical (or very close) to the price of the futures contract used for insurance. This means, index pressure has potentially a lasting effect on the price level.

Speculation by the inflow of index traders was certainly not the only cause for the price rises fueling two global food crises in 2007-08 and 2010-11, but one contributing factor among intertwined causes. Among those causal factors is the rising demand by China and India for meat and dairy products (and other raw materials) due to a rising middle class with changing dietary habits. High oil prices further diverted arable land from food to fuel production leading to a double diversion of food to feed and fuel. Factors like climate change and drought further fed concerns over global food shortages and food security. Governments across the world reacted to soaring prices with export bans of staples further feeding panic and aggravating the crisis. These developments, often addressed separately in the literature, are interlinked symptoms of a larger restructuring and corporatisation of the global food system. The interested reader is advised to listen to a recent podcast series on the topic, a proceed from a one-day workshop on Political Economy Approaches to Food Regimes.

This blog entry is based on:

van Huellen, Sophie (2018) How financial investment distorts food prices: evidence from U.S. grain markets. Agricultural Economics, 49 (2): 171-181.

van Huellen, Sophie (2018) Too much of a good thing? Speculative effects on commodity futures curves. Journal of Financial Markets (forthcoming).

van Huellen, Sophie (2017) Price Discovery In Commodity Futures Markets With Heterogeneous Agents. Bozen: Paper presented at the 2017 Commodity Markets Winter Workshop.

van Huellen, Sophie (2013) Price Non-Convergence in Commodities: A Case Study of the Wheat Conundrum. London: SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series; No. 185.

References

Cheng, Ing-Haw, and Wei Xiong (2014). The Financialization of Commodity Markets. Annual Review of Financial Economics 6: 419-41.

Fattouh, Bassam, Lutz Kilian, and Lavan Mahadeva (2013). The Role of Speculation in Oil Markets: What Have We Learned So Far? Energy Journal 34: 7-33.

Irwin, Scott H. (2013). Commodity Index Investment and Food Prices: Does the “Masters Hypothesis” Explain Recent Price Spikes? Agricultural Economics 44 (supplement): 29-41.

Irwin, Scott H., and Dwight R. Sanders (2010). The Impact of Index and Swap Funds on Commodity Futures Markets: Preliminary Results. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries, Working Papers, No.27.

Irwin, Scott H., and Dwight R. Sanders (2011). Index Funds, Financialization, and Commodity Futures Markets. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 33 (1): 1-31.

Masters, Michael W., and Adam K. White (2008). How Institutional Investors are Driving up Food and Energy Prices. The Accidental Hunt Brothers.

Mayer, Joerg (2012). The Growing Financialization Of Commodity Markets: Divergences Between Index Investors and Money Managers. Journal of Development Studies 48 (6): 751-767.

Nissanke, Machiko (2012). Commodity Market Linkages in The Global Financial Crisis: Excess Volatility and Development Impacts. Journal of Development Studies 48 (6): 732-750.

UNCTAD (2009). Trade and Development Report: The Financialization of Commodity Markets. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

US Senate (2009). Excessive Speculation in the Wheat Market. Washington D.C.: United States Senate: Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.