Brexit, Beijing, and Biden: Sino-UK Relations in a Post-2020 World

By Leigh Lawrence | 27 January 2021

On December 31st, 2020, as many eagerly waited to bid goodbye to the disastrous year, Xi Jinping’s annual New Year’s address was released. Xi, flanked by a detailed painting of the Great Wall and a startlingly bright red Chinese flag, acknowledged the difficulties of the ‘extraordinary’ year while extolling the fortitude and accomplishments of the Chinese people, the nation, and the government. Yet despite his optimistic tone, Xi’s message made clear that there would be no respite in 2021 from the continuation of the massive ongoing social, economic, and political reforms that are a key focus of his political ideology and legacy.

‘磨砺始得玉成,’ he said; only after polishing can a piece of jade be finer.

Roughly five thousand miles to the west, Boris Johnson delivered a similar speech. His tone and trademark appearance was decidedly more casual. Johnson recalled the difficult year for Britons while conceding that the start of 2021 will remain just as challenging for the nation which began the new year in strict lockdown. His tone changed when he came to discuss his most recent accomplishment: The United Kingdom’s (UK) withdrawal from the European Union (EU). In his succinct address lauding the passage of Brexit, he mentioned the word ‘free’ five times. The emphasis on freedom was clearly Johnson’s attempt to assure the British public, and possibly even himself, that 2021 will be the start of unbridled economic prosperity for the UK.

Aside from a longstanding tradition, New Year’s addresses are curated acts of political propaganda that offer clues into future policies and trajectories of the coming year. But the transition to 2021 is unlike most New Years, as 2020 was, in a word, difficult. It is a fair assumption that most people around the world, including Johnson and Xi, were more than happy to leave behind the past year of social unrest, global health crises, and economic hardship.

2020 will not be remembered solely by the pandemic. It was also a backdrop to significant societal and political reforms in both nations which will have a lasting impact on the future Sino-UK relationship. Now, standing firmly in 2021 with measured optimism on the horizon, we can look back at the previous year and analyse how and to what extent the events of 2020 have changed the world as we know it, and what the post-2020 Sino-UK relationship might entail.

Many citizens have become inured to the devastating effects of the pandemic, even as it continues to wreak havoc on the global at an unprecedented scale. As of January 15th, the global COVID-19 death rate surpassed two million, with deaths and cases continuing to rise despite the ongoing vaccine rollout. The novel coronavirus COVID-19, first identified in Wuhan, China (PRC), eventually mutated into a new and significantly more transmissible variant almost exactly one year later in Kent, England. Shortly after welcoming 2021, both the UK and Hebei Province enacted another lockdown to combat the disease’s rapid spread.

In the UK, the achievement of Brexit was a referendum on populism. The UK’s delayed integration into the EU in the 1970s was meant to promote peace, strengthen Europe’s role on the global stage, and stimulate the economy. However, the same search for independent economic prosperity and international power have driven the UK to withdraw from the agreement nearly five decades later. Now, the UK stands alone, an island in its own right.

Brexit will usher in a new era of UK international partnerships as the nation aims to reaffirm its place as a global leader in the 21st century without the strengths nor the restrictions of EU membership. Fiscally, the UK is eager to secure strong economic and trade with international partners to bolster the economy and minimize the severity of a future recession due to the fallout from Brexit and the pandemic. China’s economic clout and ongoing international development through initiatives and trade agreements incentivizes a positive Sino-UK relationship that could benefit post-Brexit British trade.

Unfortunately for Johnson, recent developments suggest with UK withdrawal has emboldened a Sino-EU relationship. The EU negotiated the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China on December 30, 2020 – one day before Brexit. The broad CAI deal, which reflects China’s investment in international trade and pragmatic diplomacy on the European continent, will likely galvanize the British government into action in the hopes of capitalizing on Chinese international investment. A post-Brexit Sino-UK trade deal would also be a symbolic achievement for the UK, proving it can merger successful international partnerships without the EU. Sadly, with no similar Sino-UK deal on the horizon, the CAI implies a repudiation of Brexit’s key argument that solidarity equates to strength.

The possibility of a future Sino-UK trade deal may also be hindered by Britain’s competing goal of asserting global leadership. Within the past year, the UK has taken a strong and vocal stance on controversial Chinese issues. One recent example is the UK’s response to civil unrest in Hong Kong. The UK maintains a special relationship with Hong Kong and harbours some political responsibility under the 1985 Sino-British Joint Declaration. In response to the 2020 anti-government protests and the Hong Kong National Security Law, the UK offered a route, albeit limited, towards British citizenship for a minority of Hong Kong citizens. This action angered Chinese authorities and prompted a vague yet threatening warning by the Chinese foreign ministry demanding the UK ‘correct its mistakes.’

Recently, the UK has stepped up its role as a vocal defender of human rights. On January 12, 2021, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab responded to the growing outcry against forced labour in Xinjiang Province, PRC. Raab’s remarks outlined actions to be taken by the British government against UK businesses that exploit such labour, while also bolstering the UK global image as a powerful moral authority. Raab made clear that the UK was a global leader by outlining these actions, ‘setting an example and leading the way.’

‘Mr Speaker,’ he said, pausing for effect, ‘We want a positive and a constructive relationship with China. We will work tirelessly towards that end. But we won’t sacrifice our values or our security.’

—

The recent challenges by the UK to China’s domestic and international authority illustrate the precarious and untenable position of current Sino-UK relations. On one hand, China has used the past year to advance pro-CCP domestic reforms, rebel against Western-oriented world order, and focus on self-strengthening and ‘national rejuvenation.’ On the other hand, the UK is aiming to both bolster its economy while reasserting its power on the global stage.

The delicate balance of asserting global moral authority versus economic incentive can only last for so long; the relationship between the two nations will likely further deteriorate. The UK is in a weak position to leverage its own moral compass against China’s when it so desperately is seeking post-Brexit trade deals, and an enticing economic incentive from China may have the power to sway Britain’s moral compass. In that sense, Brexit has weakened the UK’s position on the global stage by acknowledging fiscal weaknesses that China could easily exploit.

However, the Sino-UK relationship is not solely dependent upon the actions of the two nations. The United States also plays a unique role in the bilateral Sino-UK relationship and future development. America’s past year of widespread social reform, political turmoil, and devastatingly high infection rates from the pandemic have fundamentally changed its perceived role as a global leader. The Sino-US relationship deteriorated rapidly under Trump’s presidency, with hawkish yet half-hearted policies that ultimately hindered diplomatic efforts.

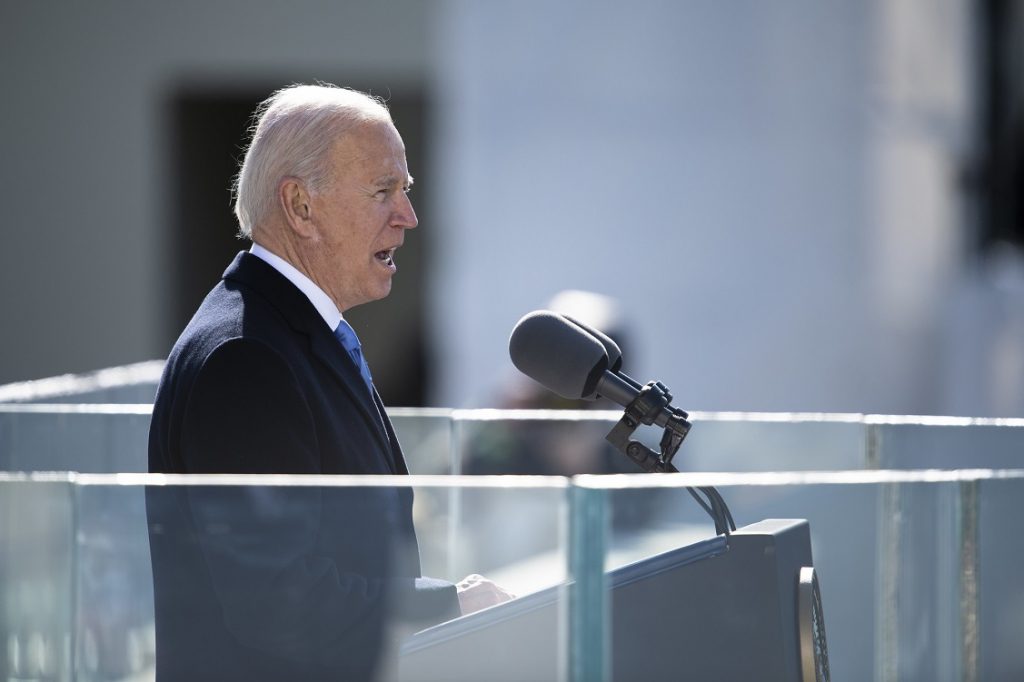

Although President Biden’s stance on Chinese issues remains vague, cabinet nominations suggest a wholehearted rebuttal of Trump policies. It is expected that President Biden will support targeted engagement and ‘democratic’ deterrence with China through multilateral alliances. This likely approach rebukes the core motivations for Brexit, arguing that global security is forged through alliances and cooperation, but broken by unilateral thinking.

The US-UK ‘special relationship’ suggests in the event of a Sino-US standoff, Britain would side with America. Likewise, China sees Brexit as an advantageous opportunity to blight the US and gain the upper hand in a trade war. In diplomacy, as with dating, three’s a crowd; the US leverages significant power over the two nations’ bilateral relations, so the future of Sino-UK ties relies heavily on President Biden.

—

Western nations’ views of China have changed significantly in the past decade. In 2010, Sino-EU diplomats praised their ‘strategic partnership’ on trade, financial crisis recovery, and politics. Less than nine years later, enthusiasm for bilateral relations has waned with the EU labelling China as a much less praiseworthy ‘systemic rival’ in 2019.

As with many relationships, things change over time. This is certainly the case with the complicated evolving bilateral relationships between the UK and China. The UK and China are two different countries, existing in two different global and ideological spaces after the events of 2020. The pandemic offers an inflection point to assess a time of change, but the two countries had already embarked on diverging and antagonistic paths on the global stage before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The events of 2020 suggest the future of Sino-UK relations will be strained while both nations attempt to mitigate domestic damage of the pandemic while reasserting international power. Outside influences such as the United States and the pandemic will also play an important role in their bilateral development. Despite their numerous differences, the two nations have a similar goal: to reshape the existing world order for global leadership. 2021 provides a new opportunity for China and the UK to re-engage on the global stage; the actions of this year will likely be a bellwether for the next phase of Sino-UK relations. Johnson cannot merely ‘cast a brick to attract jade’ (抛砖引玉) to achieve his competing post-Brexit goals, but will have to develop a strategic and balanced approach for positive Sino-UK relations in a post-2020 world.

Leigh Lawrence is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Education at St John’s College, University of Cambridge (UK). Her research focuses on moral education reform within China’s “New Era.” Leigh received her MA from Yale University (USA) in East Asian Studies and BA from Arizona State University (USA) with special affiliation with Nanjing University (PRC). Leigh was a 2019 US Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Scholar at Nanjing Normal University (PRC) and 2014 Boren Scholar to China (PRC).

The views expressed on this blog are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the SOAS China Institute.

SHARE THIS POST