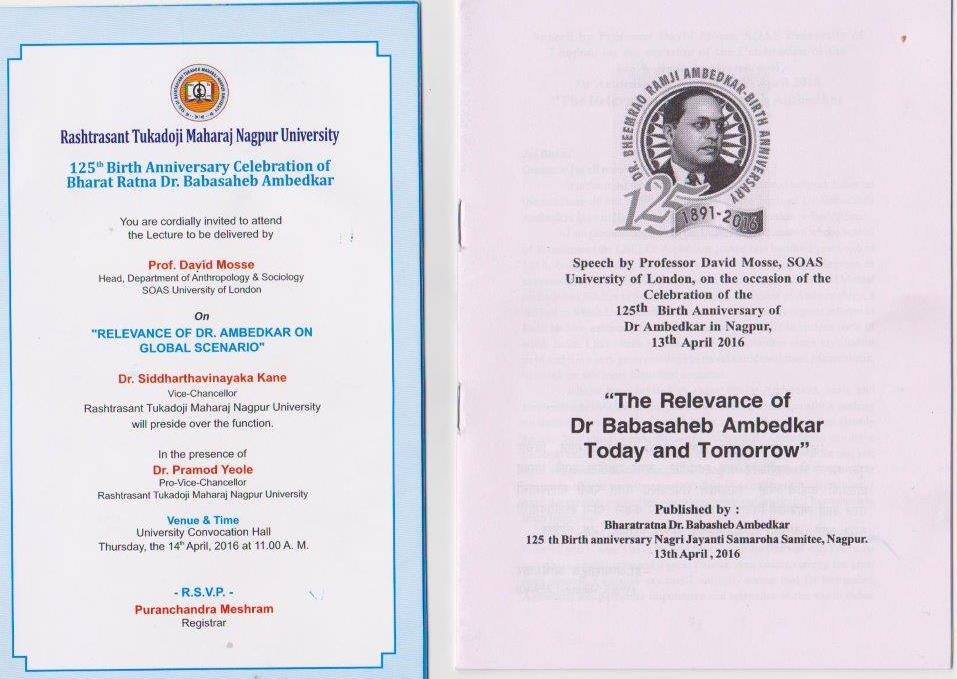

‘The Relevance of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar – Today and Tomorrow’ by Professor David Mosse

David Mosse is Professor of Social Anthropology and Head of the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at SOAS. His research combines interests in the anthropology of development and activism, environmental history and natural resources management, in the anthropology of Christianity, South Asian society and popular religion.

Professor David Mosse was invited to give a number of speeches for the celebration of the 125th birth anniversary of Dr Ambedkar in Nagpur on 13th—15th April 2016. Excerpts of the text of the presentations follow:

It is the most tremendous honour to be invited to speak today on the occasion of the 125th Anniversary of the birth of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar here in Nagpur at the place of his conversion to Buddhism. I am proud to come from the University of London whose School of Economics (the LSE) Dr Ambedkar joined one hundred years ago in 1916, being awarded both MSc and Doctor of Science degrees in economics by 1923. I belong to London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies or SOAS where I am a Professor of Anthropology, a subject in which Dr Ambedkar was also trained. I have a great interest in Dalit studies, caste and religion which I have studied in various parts of south India. I have been an admirer of Dr Ambedkar since my student days and it is a very great privilege to travel to his own state, Maharashtra, to speak on this most important occasion[…]

Ambedkar’s clarity of thought has never been more important, as we witness societies divided between those who experience the continuing humiliation of caste discrimination and violence, and those who deny its reality or significance or want to silence public debate on an inhuman outrage, the fight against which Babasaheb Ambedkar devoted his entire life… the world is awakening to the importance of him as a great thinker, leader, democrat, and guide to the teachings of the Buddha, and to what happened as a result of him. Of India’s great leaders, surely Dr Ambedkar is the one above all who continues to shape history, whose relevance is refreshed in the current economic and social moment, and whose influence extends beyond India to speak to people subject to discrimination wherever they are found.

I am aware of the many millions of Dalits for whom Dr Ambedkar is more than just a great leader: First, he embodies the capacity to overcome even the worst denigration of untouchability…Babasaheb Ambedkar’s personal struggle against repeated adversity inspires so many and gives voice to the obstacles they have to face [… ] Second, Dr Ambedkar set in motion changes to benefit the lives of millions, fighting for legal protections for Dalits, for their/your self-representation, and for equality of opportunity through reservations in education and employment. Such provisions for those marginalised were established earlier and are more extensive in India than anywhere else in the world. They are underpinned by the Constitution that Dr Ambedkar holds in the statues, which abolished untouchability, and went beyond that to enshrine a commitment to equality and recognition of historical disadvantage. [… ] Third, and perhaps most importantly the figure of Dr Ambedkar communicates to me the self-respect, the intolerance of injustice, and the voice of the those who were broken and ground down, but who now struggle against social and economic oppressions. And in the wider world, Dr Ambedkar represents something unavoidably central in our times, that is the rise of groups who have been downtrodden everywhere— the racially discriminated and economically exploited — who claim justice and common humanity in the age of equality and rationalism to which Dr Ambedkar tirelessly pointed.

So what can I say to you about what Dr Ambedkar has taught me as a scholar?

[Dr Ambedkar was] An exemplary anthropologist

First, Dr Ambedkar is able to look at Indian society and its caste system from a distance, and in the light of a different culture — the Europe and America of his time, their social and philosophical traditions… Second, Dr Ambedkar understands his adversity, not as that of an individual man, but as the consequence of the workings of a social system having millions of oppressed Dalits in its grip; a system that has to be understood in its origins, the mechanisms that sustain it, its underlying beliefs, and its effects, including deep psychological harms… I am struck thus by how Dr Ambedkar understood individual suffering as social suffering; finding the root of India’s social suffering to be caste, so that in his view the end of suffering would be the ‘annihilation of caste’.

The relevance of Dr Ambedkar today and in the wider world

Why are Dr Ambedkar’s ideas so important to understanding the lives of the oppressed today; not just in India but globally? First, Dr Ambedkar was determined to address social reality as it is not just how we’d like it to be; second, he took the perspective of those at the bottom who are oppressed; and third, Dr Ambedkar insisted that the conditions of the poor were the result not of individual disappointments but of the working of the social system under which they lived. Ultimately the question Dr Ambedkar asks of the downtrodden is not ‘Who are we?’, ‘What is our identity?’ but ‘how are we treated?’; and ‘why?’ And so he tells the world that his people are named as Dalit – the downtrodden, the broken.

I’ve learned two further and important things that follow from Dr Ambedkar’s thought here:

First, he does not separate social inequality from economic inequality, or caste from class. Indeed, Dr Ambedkar was the only person in his time to link the rights of the oppressed classes and the right of Dalits.

Secondly, the oppression of caste cannot be treated as a religious matter separate from society and economy. It is well known how critical Dr Ambedkar was of the Hindu scriptural sanction of caste and varna, but he rejected the idea that untouchability was just a cultural or religious matter.[…] The solution to discrimination lay not in religious reform but in legal rights and state intervention on behalf of the downtrodden. In this sense Dr Ambedkar removed the issue of rights from the realm of Hindu religion. The discrimination he fought against was a violation of civic and human rights in any community, any religion, region or country.

Addressing the needs the marginalised is a commitment of the international Sustainable Development Goals to ‘end poverty in all its forms’, to reduce inequality of opportunity, to provide decent work for all, ending modern forms of slavery and discrimination. I have noted three ways in which Dr Ambedkar can lead the approach to this global challenge: First, policy makers need squarely to face the social realities of continuing inequality, discrimination and marginalisation of certain groups in society, especially on the basis of caste; second, they need to listen to the experience of these groups themselves, and make their concerns part of national priorities; and third, policymakers need to understand that the conditions of the marginalised and exploited are not the result of their individual capacities but the working of social systems that allow discrimination and exclusion of certain categories of people. Dr Ambedkar points to caste as one such system, not only in India but internationally.

Democracy

I have spoken about Dr Ambedkar the scientist of society – the anthropologist. But all his thought was directed to solving the problems he identified, in particular by paving the way towards a socialist democracy. Ambedkar was a realist about the social order and its effects, but also an optimist about the ‘power of democratic institutions to bring about equality’. It is Dr Babasaheb’s clarity about what real democracy means, combined with his loyalty to the experience of the downtrodden that makes him so relevant as a guide to social policy makers, educators, politicians and reformers for the coming years, in India and internationally, especially a different nations struggle to balance to the opportunities and costs of economic change and ever-greater integration in a global market economy.

Ambedkar is probably India’s greatest thinker on democracy – which he understood in terms of the principles of liberty, equality and fraternity. Dr Ambedkar was deeply committed to freedom and the necessity of universal franchise: freedom for all to vote. Because of his deep knowledge of the way society worked he also knew that this would require special measures for those whose rightful claim to freedom was impaired by the existing social order; hence the need for reserved positions for those whose voice would otherwise remain silenced. Dr Ambedkar then insisted that political freedom is of limited value without social freedom; and that in the absence of economic democracy (that is freedom of opportunity) political democracy would be under threat.

Let me turn now to equality, which is the deeper and more embracing problem with which Dr Ambedkar grappled. “Democracy is another name for equality”, he wrote; and he was deeply concerned that freedom might not bring equality, but instead the freedom to exploit.

Ambedkar speaks thus with clarity and force to the neoliberal conditions of our time, and the social harms produced by political commitment to market freedom that reduces social protection, casualizes labour, and increases inequality and conflict.

Dr Ambedkar’s idea of equality was deepened by his commitment to fraternity, the third principle. Fraternity means that democracy is built not on abstract or isolated individuals, but on people as members of a social group. Fraternity is brotherhood and fellow-feeling, but Babasaheb insisted that this was about practice. That is to say, social interactions. He believed that kinship and belonging are at the heart of equality and necessary for the divisions of society to be rectified. Dr Ambedkar’s idea of fraternity reached beyond politics. Indeed, I see Dr Ambedkar making a further crucial step in his thinking. He concluded that “if kinship is the only cure then there is no other way except to embrace the religion of the community whose kinship they [Dalits] seek”- and by this he meant religious conversion. Conversion would effect a cure for isolation, discrimination and helplessness through the recovery of common humanity.

Necessity of Religion

And so standing here in this great place, we recall how towards the end of his life religion had become so important to Dr Ambedkar as a fulfilment of his deep thinking about society and democracy. Politics and law were not enough. Politics has failed to bring the change or the fraternity he dreamt of as the heart of democracy. As an outstanding lawyer he knew the limitations of law… Dr Ambedkar taught that we should not see religion as a matter of personal belief or doctrine. Religion mattered because of its social practices. Dr Ambedkar favoured a religion of principles (such as the principle of justice), and was against the religion of rules. Principles gave people the freedom to act, whereas a religion of rules — blind faith or superstition one might say — did not give freedom to act.

And so we come to this momentous point and this place in which Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar embraced Buddhism; and how he made a Buddhist ‘new vehicle’ or Navayana. I have learned some important things about this conversion.

(1) Babasaheb did not convert to Buddhism as an individual; he did so as a Dalit leader; as a collective act along with many thousands of others.

(2) He converted to Buddhism not to worship different gods, or any god, but as a religion that universalises the values of human life, and to embrace an idea of humanity beyond the social order. Conversion to Buddhism was a conversion to humanity.

(3) Dr Ambedkar saw that Buddhism met the necessity of identity and community to having rights of any kind. So conversion to Buddhism was also conversion into positive community and to dignity that was historically denied to Dalits in caste society.

(4) Dr Ambedkar saw that political emancipation had not freed Dalits from the indelible mark of caste, to be ordinary citizens. Buddhism gave positive value to that rejected as negative by society.

(5) Dr Ambedkar has indeed given a new meaning to Buddhism. The essential human condition is not individual suffering because of deeds, but social suffering that is produced by a society based on inequality. Enlightenment is not just individual enlightenment, but the enlightenment of a society founded on liberty, equality and fraternity; justice and compassion. In Navayana Buddhism the political, psychological and spiritual enlightenment cannot be separated from one another. And the Buddha’s message is for all.

As well as to religion, Dr Ambedkar turned to history and culture using his profound learning and personal experience to discover and recover the inner dignity of Dalits. He inferred that Dalits’ antipathy to Brahmans came from their originally being followers of Buddha- the first anti-caste reformer. And he chose Nagpur as the place of the oppressed Nag people who met Gautam Buddha.

Conclusion

Dr Ambedkar was a great nationalist, the greater for his dedication to ensuring protections and equality for the most vulnerable.

He showed that democracy requires that oppressed groups such as Dalits are authors of their own destiny, not reliant on philanthropy or the generosity of the wealthy or the benevolence of the pious.

He was the author of the idea that the dispossessed would progress on the basis of claims to rights that were theirs, by means of organisations that they and nobody else controlled. Dalits hold civic rights, universal human rights and would not depend upon the gift, leadership or patronage of others.

Even 60 years on international development policy makers are still learning this lesson. The so-called rights based approach to development goes back to Dr Ambedkar. Worldwide, the oppressed and exploited peoples desire not charity but the realisation of their rights – whether to health, education, equal treatment or justice. Babasaheb was a founding figure of such confident claims.

And what is at the root of this? Babasaheb is very clear. He speaks for the dispossessed the world over when he said they do not want simple social amelioration, “The want and poverty which has been their lot is nothing to them as compared to the insult and indignity which they have to bear as a result of a viscous social order. Not bread but honour is what they want.”

And the honour that is sought comes only through reform of the social order. This as you know far better than I, Dr Ambedkar embarked upon by all manner of means: political, legal, institutional, religious. At every step his faced resistance because his simple but powerful idea of the fundamental and universal human right of the downtrodden and the broken, were radical.

Ultimately, I have come to understand, he came back to the need to direct action at the very principles of the social system (its code). Babasaheb Ambedkar’s realisation of the necessity of conversion and the rightness of Buddhism was born out of the painful trials of his varied actions. But this was never a splitting away from the others in society, but rather embracing a universal humanity and community:

“The touchables and the untouchables cannot be held together by law — certainly not by any electoral law substituting joint electorates for separate electorates. The only thing that can hold them together is love. Outside the family justice alone in my opinion can open the possibility of love…” (1932)

Jai Bhim!

Note: The full speech has been edited for the blog by Jennifer Ung Loh, Research Associate, SOAS South Asia Institute