A Poem in Avar and Russia’s Soldiers in Ukraine

by Zayra Badillo Castro

For women, war is never over.

Rasul Gamzatov, (1923-2003) Poet, Dagestan, Russian Federation

Makhachkala is not a city often covered in the news. The capital city of the Republic of Dagestan, an administrative entity under the Russian Federation located in the North Caucasus, has become a headline since the start of the war in Ukraine. An important urban centre in the region inhabited by around 60 different ethnic groups with an estimated 25 languages spoken across its neighbourhoods and surrounding villages, it is one of the most diverse regions in the world. Last September, images of women fiercely confronting the police and protesting in the streets of Makhachkala appeared widely on social media and news outlets around the globe. These demonstrations responded to a new decree signed by Vladimir Putin ordering a military mobilisation among men between 18 to 65 years old that sought to enlist 300,000 new soldiers from all of Russia to support a new offensive against Ukraine. Six months after the start of the so-called Special Military Operation by the Russian Armed Forces, women in Dagestan and neighbouring republics of the North Caucasus have felt the misery of this war too close to home. Local activists and reporters have pointed out the disproportionate number of casualties among soldiers from this region. As early as the 26th of February of 2022, only days after Russian missiles started to fall over the skies of Kyiv, the Ministry of Defense officially named the first soldier killed in combat. His name was Nurmagomed Gadzhimagomedov, an ethnic Lak from Dagestan. The following weeks brought more news of casualties on the battlefield to the region: to Chechnya, Ingushetia, to Karbadino-Balkaria, and North Ossetia. The consequences of these losses to public opinion and the already precarious lives of women, wives and mothers, and families from this impoverished peripheral part of Russia led to a temporary ban on funerals by local authorities. A measure directed at silencing expressions of mourning and dissatisfaction. Their bravery in showing their opposition to the new decree cannot be solely analysed through these casualties and the death of their children, their sons or husbands, but also needs to be understood in the light of a historical memory moulded in the political upheavals and violent confrontations of the peoples of the Caucasus against Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union.

The largest country in the world, the Russian Federation, is divided into 21 autonomous republics, generally delimitated along ethno-linguistic lines. A policy established in the early years of the Soviet Union, it echoed Lenin’s vision of the right of nations to self-determination in creating national republics under a federative system. This model continues to exist in Putin’s Russia providing republics such as Dagestan or Chechnya with legal authority under the constitution to carry out administrative functions, provide public services and represent the cultural and political rights of the population. Nevertheless, the extent of this autonomy has often been challenged by the intervention of the Kremlin in limiting the republics’ capacity to govern independently. Moscow’s historical relation with the different ethnic minorities under its rule, from the Caucasus to Siberia, has developed differently throughout the centuries. The military strategies and exploitation of natural resources, which drove Russia’s imperial expansion and cultural annihilation in these two regions constitute a neglected chapter of world history. The war in Ukraine has introduced the average reader to the ethnic and cultural complexity of Russia’s Eurasia in a sad and brutal manner. The land of Nurmagomed was also the land of Rasul Gamzatov, an ethnic Avar and one of the most important poets in the Soviet Union, who wrote his literary works in his mother tongue, Avar. Translated into many languages, from Japanese to Spanish, his talent is recognised worldwide. Avar, such as Lak or Chechen, are among the region’s indigenous languages known as the Northeast Caucasian Languages. But in the twentieth century, Russian became the lingua franca and the language of power and social mobility, driving into extinction local languages or restricting their uses to folklore and museums. The rich linguistic history of Dagestan is not only represented in its many languages and nationalities but also by the intellectual debates documented and written in Arabic by local Muslim scholars. Islam is the predominant religion in the North Caucasus and has played a crucial role in shaping these societies in the last centuries. Its presence in the region dates back to the eighth century and the Arab conquests. Islam co-existed with the Eastern Orthodox Church of Ossetians and then of Russians alongside the Judaism of Mountain Jews and Buddhist temples of Kalmyks. It was part of a myriad of religious denominations and local worship practiced by different nationalities, converting this rather small area of the Russian Federation into a garden of faiths and spiritual confrontations.

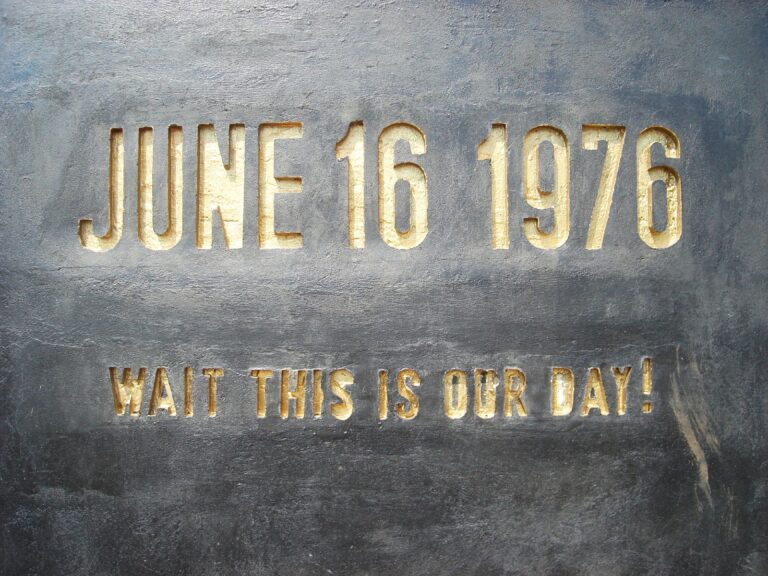

But these mountains have also seen centuries of massacres and ethnic cleansing. The Caucasus Wars in the nineteenth century marked an era of forced displacement and systematic killings in Russia’s imperial ambitions to transform this region into its province, imposing its religion and rule of law. The city of Sochi, nearby the North Caucasus and the site of the Winter Olympics in 2014, saw its indigenous population decimated. The genocidal strategies of Tsarist forces to subjugate the Circassians in its conquest of this region caused half a million deaths and a forced exile from their homeland. In 1943-1944, Soviet authorities ordered the deportation of certain ethnic groups to Central Asia and Siberia under accusations of being collaborators for Nazi Germany. Balkars, Chechens, Ingush, Kalmyks and Karachays, among other nationalities, were expelled from the North Caucasus and barred from returning. The two wars in Chechnya in the 1990s, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, witnessed gross human rights violations against the population at the hands of Russian authorities and the destruction of cities in the excessive shelling of civil infrastructures. Going through the names of the Special Volunteer Battalions serving alongside Ukraine’s Army is a journey to the historical past of the Caucasus and its legendary figures. Sheikh Mansur Volunteer Battalion takes its name after a prominent figure of the eighteenth century, an Imam and Sufi leader that stood and fought against the armies of Catherine the Great, creating a united front with the different nationalities in the North Caucasus and leading the first resistance movement against the Russians. Dzhokhar Dudayev Battalion honours the first president of the Chechen Republic of Ishkeria, who declared independence in 1991 and led its military forces against Russia’s armies to defend his nation’s sovereignty.

At the other side of the spectrum, and by Vladimir Putin’s side, sits Ramzan Kadyrov, the current president of the Chechen Republic, another territory under the Russian Federation, who has become a staunch supporter of the invasion of Ukraine and an important ally. The Kadyrovites, as his soldiers from the Chechen Unit of the Russian National Guard are called, played a decisive role in capturing the city of Mariupol and fighting major battles against the Ukrainian army. But they have also suffered considerable losses, and in September, women in Grozny, Chechnya’s capital city, publicly voiced their discontent with the war and the new decree for military mobilisation – a courageous action in a territory known for the terror of his leader and his secret services. Far from the North Caucasus, in Siberia, lies the Republic of Tuva and the hometown of Putin’s minister of defence, Sergei Shoigu. A native Tuvan, without much military experience, but a stunning mansion on the outskirts of Moscow, designed after a Buddhist temple, has been the public figure delineating the strategy of this war. His kinsmen have suffered some of the worst losses in Ukraine, alongside soldiers from Dagestan and neighbouring Buryatia. Tuva’s life expectancy is barely 48 years, lagging behind Russia’s socioeconomic indicators and living standards. Military service provides young Tuvans the only opportunity for financial prosperity in their isolated republic. Men in the North Caucasus faced a similar dilemma, and it is common for them to be enlisted at a young age, as the armed forces provide their best chance out of poverty. Tuva’s relationship with Moscow differs from the experience in the North Caucasus. Their territory came under direct Russian rule only in 1944, with its incorporation into the Soviet Union after decades of Tsarist and Communist influence in its politics. Until 1911, Tuva was part of the Chinese Empire and its cultural landscape share similarities with its neighbours across the Mongolian frontier and beyond the Sino-Russian border. The population of Tuva has historically practised pastoral nomadism, and the main religion is Tibetan Buddhism, but many continue to follow the rituals and traditions of Siberian shamanism. Recently, the world has come to learn about this republic thanks to the talent of the Tuvan throat singers. They have appeared in documentaries and musical festivals, delighting audiences with their unique vocal technique. The enormous complexity of Russia and its more than 170 nationalities proves a challenging task for analysts and war correspondents, who are puzzled by the various alliances provoked by the war in Ukraine. There is a danger in the media, with journalists simplifying the narrative of Russian war crimes under headlines of Mongol hordes or Caucasus savages. These orientalists’ tropes play well into Putin’s civilisational discourse to justify the invasion of Ukraine. The hordes, in his words, are others, personified in an imaginary West coming to loot Russia of its sacred values and moral codes. The Asian looks of the Russian Armed Forces and the Alllahu akbar of the Kadyrovites reported on the news reveal a dark past of conquest in Russia and violent repression against ethnic minorities. Days after the death of Nurmagomed was announced, his friends and schoolteacher shared a video of him reciting a poem by Rasul Gamzatov. Among the many poems published by Gamzatov, there was one, especially important for soldiers, that became a popular anti-war Soviet song in the 1970s, “The Cranes”. Composed during a visit to Nagasaki, this poem continues to be a reminder to the mothers of Dagestan, Tuva or Ukraine that “for women, war is never over” and

… that soldiers fallen,

Rasul Gamzatov, ‘The Cranes,’ translated by David M. Bennett

whom bloody battle fields have rendered dead,

were buried not in soil to be forgotten,

but turned into white cranes in flight instead.

[…]

Some day in that formation I’ll be flying;

I’ll sail into the skies on my rebirth,

And from the heav’ns with crane trump I’ll be crying

to those of you I left upon the earth.

Recommended readings:

Akiner, Shirin. Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union: An Historical and Statistical Handbook. Rev. ed. London: KPI, 1986.

Chakars, Melissa. Socialist Way of Life in Siberia: Transformation in Buryatia. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2014.

Colarusso, John and B. G. Hewitt. Nart Sagas From the Caucasus: Myths and Legends From the Circassians, Abazas, Abkhaz, and Ubykhs. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Dobie, Jon, and Asaf Sirkis. Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia, Siberia. London: SOAS, 2008.

Forsyth, J. A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony, 1581-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Yemelianova, Galina M., and Laurence Broers. Routledge Handbook of the Caucasus. Abingdon: Routledge, 2020.

Zelkina, Anna. In Quest for God and Freedom: The Sufi Response to the Russian Advance in the North Caucasus. London: Hurst & Co., 2000.

Zayra Badillo Castro (she/her)

She/her

Contributor 2023

Zayra Badillo Castro completed a PhD in History at SOAS with the dissertation, “Transforming Socialist Modernities: Tashkent and an Uzbek Project of a Central Asian Metropolis, 1953-1983.” She has conducted extensive archival research in Russia and across Central Asia and is the recipient of several fellowships, which include the FLAS (Foreign Language and Area Studies) and Title VIII for the Study of Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Badillo Castro also holds an MA in International Studies and Diplomacy and has been a visiting researcher at universities in the United States and Uzbekistan.

Twitter: @zaybad

Instagram: @caribestan

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London