SOAS History Blog Podcast Ep 6: Nada Moumtaz

More about this episode

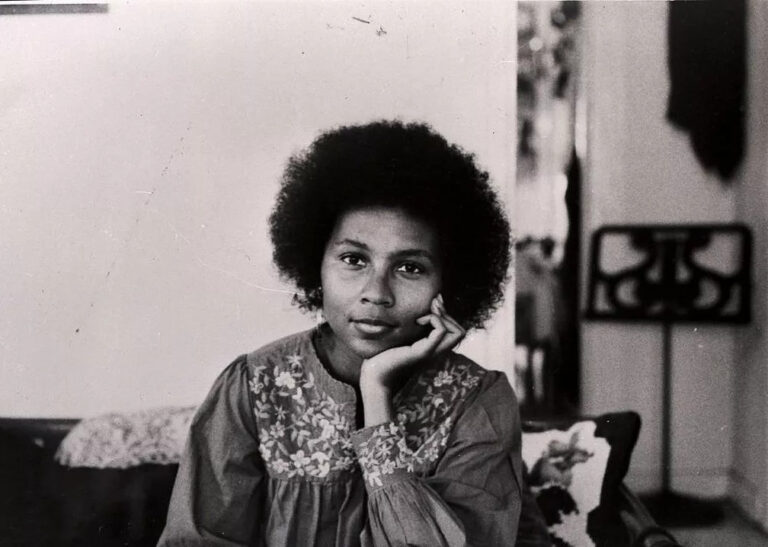

Dr Nada Moumtaz

Interviewee and author of God’s Property: Islam, Charity and the Modern State (2021).

Interviewed 2022.

Al Jawhara H. Al-Thani, John Michael Gurklis, and Nour Alsabagh

Interview Team

Histories of Capitalism and Race Seminar Series SOAS 2022

SOAS History Blog

Ellan A. Lincoln-Hyde: Editing and production

Jasmine K. Dosanjh: Transcription

Podcast Transcript:

Introduction (Ellan): This is a SOAS history Blog podcast to read and hear more content from the SOAS History Blog, go to: blog.soas.ac.uk/soashistoryblog.

Intro: Atalas Shoulders Koi-discovery (used with artist’s permission)

Jawhara: Welcome to our podcast, we are joined here today by with Nada Moumtaz who’s an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto, we’re very glad to have her here. She’ll be giving a public seminar which will also be recorded and uploaded. We really look forward to speaking with you today. This will be a short and casual conversation with you and to introduce ourselves, as the hosts. We have John Michael.

John Micheal: Hi, I’m John Micheal. I’m a second-year MA student at SOAS and I study history with a focus on the Middle East.

Jawhara: And I’m Jawhara. I’m a first-year PhD student, here at SOAS and I work on the history of slavery in the modern gulf. Nada, would you like to introduce yourself?

Nada: Yes, I am Nada and as you said, I just became an Associate Professor.

John-Micheal and Jawhara: Congratulations!

Nada: I’m an anthropologist but I am in the department for the study of religion and near Middle-East civilisation and I am very excited to be here.

John-Michael: I guess, I’ll ask the first question. YDo you want to give a brief overview of your book God’s Property: Islam, Charity and the Modern State, and you know, describe the motivations that you had for the project more broadly?

Nada: So, the book looks at a particular form of land endowments which are called waqfs, in Beirut Lebanon and is a historical anthropology. I would call it. Of these endowments in Beirut, I am particularly interested in its revival and how that revival really changes. What it claims to be just reviving, because of our modern conceptions of charity, economy property, etcetera. So perhaps my motivation since I said, it’s part of the revival was the study of the revival because I grew up in Beirut at the time of the revival, and that was kind of a different form of religiosity than what I have grown up with. So, I was interested in examining this revival better and understanding the forms, it was taking, etc. And the other part of my interest was as an architect, as an undergrad in architecture and I did an undergrad in architecture my final year project was about these big capitalist shopping malls that were opening all over everywhere. So, I had a big interest in capitalism and the commercialisation of space. So, my interests were really to try and understand, perhaps both these aspects of life in Beirut in the late 1990s, early 2000s when I applied for the PhD.

Jawhara: That’s incredibly interesting to see how your background and particularly your even undergraduate work have informed your project. How also do you see your work putting into these wider fields of…beyond architecture and history and anthropology but also within Middle Eastern studies, religious studies and other fields in general?

Nada: When you’re writing a book, usually people ask you who’s your audience, because that may frame the way, you’re going to frame the book. When I was writing, I was particularly interested in sort of questions, rather than writing to particular audiences. I’m trying to really understand these processes and what is particularly going on, etcetera. But then you start to behave, to become more specific about the literature to have to talk to about, etcetera. And so, you have to then in certain ways, and so I feel sometimes that my book fits awkwardly between all of these different disciplines. I am trying to draw on different disciplines through history and Islamic studies. And I came to Islamic studies late, that was not really my training, but I definitely think that the easiest way would be to place it within that but my interest, however, are broader as well, because I’m interested in larger anthropological questions- about the making of religion and the making of the economy? So, how do our conceptions as I mentioned at the beginning, you know family, charity and piety, all of these change and re-do, re-make certain practices like the waqf in Islamic tradition. So that’s how I would answer that question.

Jawhara: To follow up, how do you perceive, in addition, to the multi-disciplinary approach that you’re taking, how do you perceive historical anthology? Which is how your book has often been characterised, and the kinds of questions, it can provide beyond standard history as the discipline or ethnography and more common anthropological methodologies?

Nada: It is true that I frame it as a historical anthology in the book. It is an attempt to try and account for the fact that, I started out wanting to do something much more contemporary and anthropological and ended up doing much more history than I expected. Partly, because there was no history of waqfs that was written that I could really draw on. There were a lot of, you know, historical studies that are very much pre-nineteenth-century- most of the time. And, because the narrative of waqf is that, you know, it almost disappeared between the 19th century and 20th century. Especially, with colonial projects that made it disappear. So, in the Muslim world, as well as the adoption of restrictions of what kind of waqfs people could do, etcetera. So, you could see how I didn’t really find as many studies of the contemporary waqf. With the assumption that there are barely any left. So, it is anthropologically grounded particularly, in the questions I’m interested in particular, as I mentioned, in these theoretical questions about transformations in conception and particularly because it talks to concerns of the present. And I am very clear about that. That this is also about me trying to better understand how the waqf is done and how we can do it differently, better perhaps, etcetera. And, so, I would say that for historians, it’s that presentism might be a bit too much sometimes. Even though, I would claim that all history is presentist. Of course, it’s not just me who says it, everybody says it, all my friends also say that. So…but… I would say that the flexibility I tried to bring to the table, in the book, the process of doing research and the process of accessing certain archives are not…Also stumbling upon certain documents and how this shapes the histories, I am able to tell has to be more present and more common histories, that are not perhaps as inclined to include the historians of (…) An extended discussion of the historians’ craft and process of making their own archives. And for anthropologists also it’s not just history, that history that is a background section in the intro or in the first chapter but really being very attuned to these changes, to the concept that we are using today and being aware of their deeper history and genialities.

John-Micheal: I think it is interesting because earlier you mentioned that sat awkwardly in between these camps. Do you think that is in part because of where you come from at it, or do you think that perhaps that waqf in itself? You know sort of it’s straddling these sorts of dichotomies that are, kind of, made around it. Do think it’s in part because of that? And also, what sort of broader interventions do think focusing on something like waqf can bring to historical, anthropology or historical anthropology? Whatever, you know, what sort of field because you know it seems to touch into so many?

Nada: It is true that waqf in and of itself because I like to play with it a lot, is such a topic that defies classification? Sometimes I joke and say it’s like a total social fact like marshal/marcia homes talk about it. It overlaps with so many of these distinct spheres, that we think about. It’s economic but it is also architectural. It is also something that is political, and it is religious. It’s all these things that come together and so I can say that there perhaps we can I can just that yes, it is something that has to do with the waqf, but I also say that has to do with approaches because it is methodical. I would say that each discipline brings its own methods and questions, and I would say it is not just about the waqf itself but what kind of tools I am bringing to the table to try and understand it. Because we think of the world very much today, when we want to do analysis, there’s the political scientist, there is the economist, and there is a sociologist. We disassemble the world and look at it from different perspectives without looking at how all of this works together to create the world and better understand it. Each one focuses on one thing and trying to bring them all together again. Well, I am just stealing from Eric Wolfowitz but you know. That is a lesson I have learned perhaps. In terms of the interventions, and methods as we discussed I think it was a big part of what I am thinking about for religious studies. I think that was the way I try to think about secularisation beyond thinking of religion and politics but rather religion and economy is something new that hasn’t been done, as much in expending that kind of narrative about secularisation. Anthropology is also a way to think of studying the past, how do tradition and all these ways of thinking continue to exist? You can think of that also with capitalism, like how property like waqf continues to exist within and how they continue to perpetuate themselves? So I’m interested in these kinds of different ways of life, different forms of property and how they continue to be alive and lively, despite what we think of as this raw capitalist world.

John-Michael: One more question?

Jawhara: What about a quick anecdote that you have from the field? Anything fun you can share when you were out doing your research?

Nada: It is not really a noticeable memory, but it was kind of the realisation that after I started my research, I discovered that my family had a waqf. So, in some ways, it was crazy to realise that this history has been so obscure that even though my family had to waqf and a dispute, still going. It’s also that I didn’t know about it. It talks about what families share and what they don’t share with the, you know, younger folks. So, it seemed mind-numbing to me that I had gone all the way to the US and done a PhD. And I come here and come up with this project that is more probably relevant, and it turns out that I’m actually writing about my family.

Jawhara: Would you like to let us know what you’re working on now? Any new projects or are you taking a bit of a break? (Laughing) After…

John-Michael: A well-deserved one.

Nada: I am actually trying to decide what to do next? I mean, there’s a bunch of things I’m interested in. One of them has to do with some of the court documents I had found in the process of my research on the waqfs in my book, which have to do with Urban rights. So, how do you plan a city before urban planning? So, all of that kind of neighbourly, right? Like, oh, “you are opening a window into my court? You are closing light from me?” So, it’s about regulating these relations among neighbours. “You are seeing into my courtyard’ and all of that stuff. And so, trying to think about whether these forms of regulating the city can? What do they do? And we can perhaps think of them today as a different kind of motor planning? So that’s one. And the other one has to do without a longer project that I would need to dig into the literature and it kind of builds also on my earlier work on the waqf which is filial piety? So, a lot of works are done for families and filial piety is really important in the Islamic tradition? And so really to look at that in the quote on quote “route crisis” in Lebanon right now which is beyond, you know. Beyond description, there is the financial collapse and a monetary collapse and most people’s savings have disappeared and so what do… for people who are ageing, for example, who spent their whole lives saving all of this money. Now they don’t have money. And so, what is the responsibility of children towards their parents when they aren’t in such a situation? When, for example, most children had to immigrate to be able to find jobs? To be able to live. How do you support your family? What is the good life that these older parents want to have? What is a good life when one is nearing death? These are existential questions, but that build on…and these are my interest about filial piety. Of course, they also are personal, you know as you can imagine, but I think they also allow you to touch upon questions that are really relevant everywhere. I think we all have to deal with such questions and in addition to dealing with questions of labour, who does the about of care of elders? What is an ok setup? Do people expect to live in these elderly homes? All these different spheres that come together. I can think of architecture, homes and labour and all these come together under that particular question of elderly care?

John-Michael: Well, thank you so much for you know, sitting down and talking to us with really inspiring and thoughtful answers. Guess we look forward to hearing the rest of your talk later today? Inshallah, and thank you.

Nada: Thank you for having me.

Outro (Ellan): You have been listening to a SOAS history blog podcast, this episode was edited and produced by Ellen Lincoln. For more content from the SOAS history blog find us at blog.soas.ac.uk/soashistoryblog, and follow us on Twitter at @soashistory, and on Instagram at @soashistoryblog.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London