Palestine, Apartheid and the International Criminal Court: Optimism or Caution?

by Reece Stock

CW: Brief mentions of acts of violence including sexual violence; extended discussion of ethnic cleansing and apartheid practices.

The State of Israel was founded on 14 May 1948, not just as a state for the Jews, but as a Jewish state. The idea of a Jewish ethnostate in historic Palestine was rooted in Zionist ideology and legitimised internationally by failed attempts from Britain and the United Nations to partition the land of Palestine into two separate states: one for the Jews and another for the Palestinians. Under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion, this Jewish ethnostate was achieved through a merciless and systematic ethnic cleansing of the Arab population that had called Palestine its home for thousands of years.[1] However, Zionists soon discovered that maintaining a settler-colonial ethnostate is no easy task, particularly when a sizable native population remains within the borders of the state. As such, Israeli governments have resorted to discriminatory and oppressive policies towards the Palestinians in order to maintain a Jewish state in historic Palestine. It is the intention of this article to explore the historical and legal dimension of apartheid as a comparative lens in Israel-Palestine, with a particular focus on what this could mean for the current International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation into crimes against humanity committed by Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT).[2]

A note on terminologies and technicalities

The ICC is investigating war crimes and crimes against humanity committed within the Palestinian territory of the West Bank, east Jerusalem and Gaza which has been occupied by Israel since 1967. Its investigation will not, and indeed cannot, address instances of ethnic cleansing between 1947 and 1967. It is currently unclear whether the investigation will address the accusations of apartheid because, although the Court is responsible for prosecuting the crime of apartheid, there is no precedent in international law for the prosecution of this crime. Ethnic cleansing is the forced removal (through displacement and/or genocide) of a population from a territory, apartheid is a system of domination and control of one racial group over another racial group within the confines of state control. All three elements of ethnic cleansing, apartheid and occupation are at play in the historical contextualisation of the history of this region, but not all three are addressed simultaneously in either reporting or investigations. This article acknowledges the differences and difficulties which these terms bring with them but unites all three in its analysis as they are undeniably linked.

A Brief Historical Overview, 1947-1967

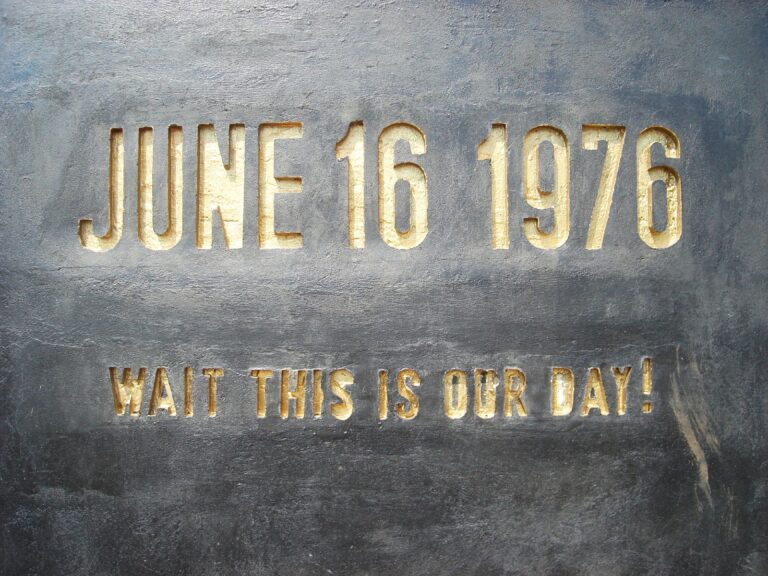

The period of history between 1947 and 1949 is now known to the Palestinians as the Nakba (which means ‘catastrophe’ in Arabic). The Nakba brutalised and devastated the Palestinian population, resulting in the murder and rape of thousands and rendering hundreds of thousands indefinite refugees – the exact number of victims of these crimes are still largely unconfirmed. By the end of 1949, over 500 Arab villages had been depopulated and destroyed and 750,000 Palestinians expelled from the country, reducing the Arab population of the newly established State of Israel to just 156,000.[3] For Zionists, this ethnic cleansing was a necessary step in the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine as the Arab Palestinians outnumbered the Jews significantly. Even by 1947, after prolonged attempts by the Zionist movement to encourage Jewish immigration to Palestine, Jews only constituted roughly 30% of the total population. It was deemed that the only way to achieve the Zionist dream of a Jewish state in historic Palestine was through the forcible transfer of a significant number of Palestine’s Arabs.

However, the ethnic cleansing of Palestine was not entirely achieved, meaning Israel was left with an Arab population that was greatly reduced but not insignificant. Moreover, the expelled Palestinians were not absorbed by neighbouring Arab countries, as the Zionists had hoped, but instead clung to their distinct Palestinian identity and hoped to eventually return to their homes. As a result, when the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, east Jerusalem and Gaza began in 1967, Israel was left with a sizable Palestinian population to contend with. In order to retain the distinct Jewishness of the State of Israel, successive governments have pursued a number of discriminatory policies towards Palestinians which have been termed ‘hafrada’ – which means ‘separation’ in Hebrew. Many critics, however, have instead called these policies ‘apartheid’.[4]

Comparing Hafrada with Apartheid

Israel has enacted various pieces of legislation to protect the exclusionary nature of its ethno-nationalist state. These are considered defensive measures by many Israeli Jews who believe maintaining a Jewish state in Israel is essential to the survival of the Jewish people. Such policies are reminiscent of other settler-colonial projects throughout history, particularly twentieth-century apartheid South Africa. Firstly, the Israeli Population Registry Law (1965) requires all Israeli citizens to declare their ‘nationality’ from a list which includes ‘Jewish’, ‘Arab’ and over 100 other possibilities.[5] ‘Israeli’, however, is not an option on this list. This has allowed Israel to maintain the illusion of equality between Jews and Arabs as both groups share Israeli citizenship, whilst privileging those with ‘Jewish’ nationality over those who declare as ‘Arab’.[6] Comparisons have been drawn between this law and apartheid South Africa’s Population Registration Act (1950) which categorised South Africans by their race in order to afford privileges to whites over blacks, ‘coloureds’ and Indians. One of the ways Israel has privileged Jews over Arabs is by tying certain rights, such as access to housing and higher education, to military service in the Israel Defense Forces – which all Israeli Jews are required to undertake but Palestinian Israelis are excluded from. It is through policies such as this that Israel has been able to obscure its discriminatory practices and maintain a façade of equality between Jews and Palestinians in Israel. Secondly, in the Occupied Territory, it is becoming clear that Israel is pursuing a policy of fragmentation and cantonisation of the Palestinians which is strikingly similar to apartheid South Africa’s bantustans. Like the superficial autonomy of the ‘homelands’ in apartheid South Africa, Israel has given the West Bank and Gaza Strip a degree of autonomy, but in name only. This is intended to give the impression of Palestinian independence without actually relinquishing any of Israel’s control over the lives of Palestinians living in the Occupied Territory.[7] It also has the effect of dividing the occupied Palestinians, as well as their political institutions and resistance movements. They are split governmentally between the West Bank – which is governed by the Palestine Liberation Organisation, and Gaza – which is now administered by Hamas. They are also physically separated as the two Palestinian regions are completely cut off from one another by Israeli territory. Finally, the most pernicious of Israel’s discriminatory laws is the recent Nation-State Bill (2018), which officially enshrined Israel’s status as a Jewish state in law, claiming that Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people only. This controversial legislation jeopardises the rights of non-Jewish citizens of Israel and denies Palestinian Israelis their right to self-determination, ensuring Jews remain the dominant ethnic group in Israel long into the future.[8] Since its passing, the bill has been widely condemned as an apartheid law, highlighting the challenges of maintaining a state that is both ‘Jewish’ and ‘democratic’. As such, Israeli apartheid bears resemblance to twentieth century South African apartheid yet has its own particularities as a twenty-first century apartheid regime.

Apartheid and International Law

According to the 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the 1976 United Nations Apartheid Convention, apartheid is defined by international law as ‘inhumane acts committed in the context of an institutionalised regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group’.[9] A study by the Human Sciences Research Council in 2009 concluded that, within the context of Israel-Palestine and for the purposes of the definitions of apartheid in international law, ‘Israeli Jews’ and ‘Palestinian Arabs’ could be considered ‘racial groups’.[10] Between 2020 and 2022, four reports by the human rights organisations Yesh Din, B’Tselem, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have argued that the draconian methods Israel has resorted to in order to ensure Jewish supremacy over the Palestinians across Israel and the OPT constitute the crime of apartheid under international law. These human rights organisations have come to this conclusion by applying the international legal definitions of apartheid to the situation in Israel-Palestine, evaluating the effect that individual policies have had on Palestinians living under Israeli rule. The reports have shown how Israel’s discriminatory policies intentionally segregate the Palestinians through restrictions on movement, limit access to Israeli institutions, and deny Palestinians their civil rights, as well as residency and nationality rights in both Israel proper and the Occupied Territory.[11] These reports have put forward the case that such actions are racially motivated with the intention of ‘maintaining Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea’ and ‘cross the threshold of apartheid’ set by the Rome Statute and Apartheid Convention.[12] As a result, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International called on the International Criminal Court to include the crime of apartheid in its investigation of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. After a preliminary examination in 2019, an ICC investigation is now underway, formally beginning in March 2021. However, whether this investigation will take onboard the recommendations of these human rights organisations and include an examination of Israeli apartheid remains to be seen.

The Case in the International Criminal Court since 2021

The International Criminal Court, founded in 2002, is responsible for prosecuting individuals for crimes against humanity by bringing them to trial at The Hague. To date, the ICC has conducted twelve investigations, nine preliminary examinations and issued 46 indictments, many of which have been within the region of sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, it is worth noting that the Court has not yet found a single person guilty of crimes against humanity outside of sub-Saharan Africa.[13] Furthermore, the jurisdiction of the Court is limited as it is only permitted to prosecute crimes committed within member states. Israel has tried to leverage this to its advantage by claiming that the ICC does not have jurisdiction in the Occupied Territory since Israel is not a party to the Rome Statute and Palestine’s statehood is internationally disputed. Despite this, on 5 February 2021 the ICC ruled that it does indeed have jurisdiction across the West Bank, Gaza and east Jerusalem, thwarting Israel’s transparent attempt to block an investigation into its own crimes in Palestine.[14]

This ruling was met with condemnation from Israel and its allies, in particular the United States and Germany, who challenged the Court’s claim to jurisdiction in the OPT.[15] Israel’s prime minister at the time, Benjamin Netanyahu, went so far as to brand the decision ‘pure antisemitism’, a common tactic by Israel to shut down any condemnation of its actions. Whilst the ICC, under former prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, is to be commended for its strong response to Israel’s challenge to its jurisdiction, it is worrying that the US and Germany, member states of the ICC, have been so vocally critical of the Court’s decision. Lacking any significant power of its own, the Court relies on the cooperation and respect of its members. Without the support of influential states its findings on any individual case can be elevated or diminished significantly. As such, there has been very little discussion of the ICC investigation, even amongst Palestinians and their allies, as it is believed that the prospects of the ICC bringing Israeli officials to trial in The Hague are slim.

The Outcome and What Happens Now

Now that the ICC’s preliminary examination has concluded and its investigation into crimes against humanity in the OPT is underway, Palestinians have been left to speculate, and hope, about what its outcome may be. Previous cases tell us that the Palestinians are in for a long wait. Of the 46 indictments issued by the ICC throughout its history, 20 are still ongoing and only eight have ever ended with convictions and the guilty party serving sentences for their crimes. As mentioned earlier, all of these convictions were related to cases in sub-Saharan Africa and anyone standing trial for war crimes committed by a country outside of the global south is almost unthinkable. Moreover, the investigation itself is set to be a lengthy and protracted affair and further questions of jurisdiction are likely to arise as Israel is sure to do everything in its power to delay the investigation for as long as possible in the hopes that the ICC will eventually be forced to close it down altogether.[16]

Additionally, Fatou Bensouda, who has consistently viewed the Palestinian’s case with sympathy, stepped down in June 2021 when her term as prosecutor expired. It remains to be seen what stance her successor, British lawyer Karim Khan, will take towards the ICC’s investigation in Palestine. Unfortunately, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the many war crimes being committed there, have diverted the attention of the Court and pushed the Palestinian case into the background. However, regardless of its outcome, the investigation has the potential to shape the boundaries of the Israel-Palestine question for the foreseeable future. If an examination of apartheid is not included, it would reinforce the idea that Israel’s hostile acts towards the Palestinians only began in 1967 with the start of the military occupation, rather than with the Nakba in 1948. This would play into the hands of Israel by obscuring the interrelation of ethnic cleansing, apartheid and occupation in Israel’s regime of domination over the Palestinians. Despite these challenges, the ICC investigation provides the best chance of halting Israeli annexation of the West Bank and, for this reason, it will be watched closely by Israelis and Palestinians alike. For now, the Palestinians have a long road ahead of them and further challenges are sure to arise. The prospect of Israeli officials facing justice for the many crimes committed against the Palestinians in over eight decades of Israel’s history will surely provide a source of hope for many, However, Palestinians know better than anyone not to place too much faith in international institutions, and for this reason, they are sure to be cautiously optimistic as the investigation unfolds.

[1] Ilan Pappé, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (London: Oneworld Publications, 2006).

[2] This article is partially informed by my recent dissertation research completed as part of my degree in History at SOAS University of London.

[3] Josh Ruebner, ‘Five things the United States knew about the Nakba as it unfolded’, Middle East Institute, 13 May 2022.

[4] Seraj Assi, ‘Call it what you wish, it amounts to Apartheid’, The New Arab, 6 April 2017.

[5] ‘So This Jew, Arab, Georgian and Samaritan Go to Court’, Ha’aretz, 28 December 2003.

[6] Jonathan Cook, ‘”Visible Equality” as Confidence Trick’, pp. 123-160 in Ilan Pappé (ed) Israel and South Africa: The Many Faces of Apartheid (London: Zed Books, 2015).

[7] Leila Farsakh, ‘Apartheid, Israel and Palestinian Statehood’ pp. 161-187 in Ilan Pappé (ed), Israel and South Africa: The Many Faces of Apartheid (London: Zed Books, 2015).

[8] BBC, ‘Jewish nation state: Israel approves controversial bill’, BBC News, 19 July 2018.

[9] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, A/CONF.183/9, 17 July 1998, entered into force 1 July 2002, art. 7(2)(h); International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, G.A. res. 3068 (XXVIII)), 28 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 30) at 75, U.N. Doc. A/9030 (1974), 1015 U.N.T.S. 243, entered into force 18 July 1976, art. 2.

[10] Human Sciences Research Council, ‘Occupation, Colonialism, Apartheid? A re-assessment of Israel’s practices in the occupied Palestinian territories under international law’, May 2009.

[11] Human Rights Watch, ‘A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution’, April 2021.

[12] Amnesty International, ‘Israel’s Apartheid Against Palestinians: Cruel System of Domination and Crime Against Humanity’, February 2022.

[13] Richard Falk, Palestine’s Horizon: Towards A Just Peace (London: Pluto Press, 2017).

[14] International Criminal Court, ‘Statement of ICC Prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, respecting an investigation of the Situation in Palestine’, 3 March 2021.

[15] Stefan Talmon, ‘Germany publicly objects to the International Criminal Court’s ruling on jurisdiction in Palestine’, German Practice in International Law, 11 February 2021.

[16] Lori Allen, ‘The ICC in Palestine: Reasons to Withhold Hope’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 17 February 2021.

Further Reading:

Adem, Seada Hussein. Palestine and the International Criminal Court. The Hague: Asser Press, 2019.

Erakat, Noura. Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine. California: SUP, 2019.

Falk, Richard. Palestine’s Horizon: Towards A Just Peace. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

Khalidi, Rashid. The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonial Conquest and Resistance. London: Profile, 2020.

Pappé, Ilan (ed). Israel and South Africa: The Many Faces of Apartheid. London: Zed Books, 2015.

Pappé, Ilan. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine. London: Oneworld Publications, 2006.

Tilley, Virginia (ed). Beyond Occupation: Apartheid, Colonialism and International Law in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. London: Pluto Press, 2012.

Editors’ note: The editors would like to thank Dr Yair Wallach (Senior Lecturer in Israeli Studies, SOAS University of London) for feedback and contributions to this piece.

Reece Stock

he/him

Reece is currently studying on the MA History programme at SOAS, after graduating with a BA in History and Politics from Queen Mary University of London in 2021. He specialises in the history of the modern Middle East and his master’s dissertation, titled ‘From Johannesburg to Jerusalem: applying “apartheid” to Israel-Palestine’, examines the strengths and weaknesses of applying the term apartheid to the current situation in Israel-Palestine.

Twitter: @reece_stock

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London