The Menopausal Matriarchs of West Africa

by Amelia Storey

Any exploration into West African history soon surfaces contradictions and blatant neglect when it comes to older, postmenopausal women. Colonial-era sources tend to overlook older women entirely, yet, even so, glimpses seep through of the esteemed female elder. The status of postmenopausal women, its origins, manifestations and development during the twentieth century are the subject of my Undergraduate dissertation “The Historical Pre-Eminence of the Older Woman in West African Societies.” Based on the research of my dissertation, the focus of this article is how the menopause shaped the status of older women.

When, in 1929, the British anthropologist R. S. Rattray remarked that a succession of Queen Mothers in the Dwaben kingdom of the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) had not only ruled in the absence of a suitable male chief, but had after their deaths been “buried in the Barim (mausoleum) of the Chiefs,” he brusquely explained that this was “only possible owing to the fact that [they] had passed the menopause” (Rattray 1929: 173-174). References to the high-ranking positions of women in West African societies are sparse enough in the colonial record, so mention of the menopause by a British scholar at this time is somewhat remarkable. However, what is of still greater significance is that Rattray describes prestige granted to women on the basis of their postmenopausal state.

Although women did not need to be postmenopausal to be a Queen Mother (ohemaa) in Dwaben and elsewhere in Asante, they evidently attained further distinction if they were. Far from being socially discarded following the end of their reproductive days, postmenopausal women occupied exclusive and significant roles in all spheres of West African life – social, political, religious and ritual. Whilst these positions may be described as matriarchal, they were also distinctly menopausal. An attempt to explore the reasons for this deference towards postmenopausal women and its translation into daily life shall follow.

The Significance of Menopausal Markers

The most obvious characteristic of the menopause is the cessation of menstruation, a process which ultimately sees a woman have her final period and stop being able to conceive children. It is no secret that, in the West, this transition is shrouded in mystery, taboo and negative connotations. Given the extent to which childbearing and fertility is celebrated in West African culture, it would be easy to assume that the loss of a woman’s fertility would be similarly unglorified. On the contrary, it is often the marker of a woman’s transition to a new, pre-eminent social position. As one 90 year-old Ghanaian woman described: “When a woman stops menstruating she moves from ababaawa [young woman] to become opanyin [elder]” (Van der Geest 1998: 455).

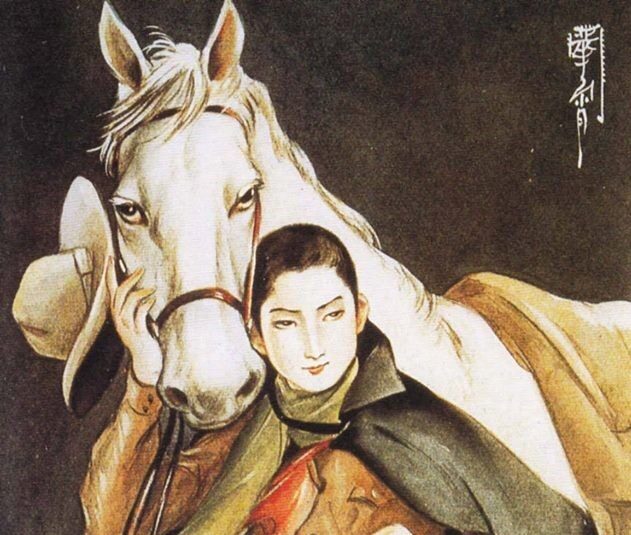

A major benefit which this change brought to older women was freedom from menstrual taboos. On a practical level, this meant no longer having to isolate during their menstrual periods (a custom widely practiced). Simultaneously, it opened the door to certain activities hitherto prohibited. For postmenopausal Asante Queen Mothers, one such activity was war. A handful of these women found acclaim by participating and leading in conflict, a role denied to those still menstruating. Amongst these was the renowned Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen Mother of Edweso (see Figure 3), who famously led the war against the British in 1900 (Aidoo 1977). As in war, postmenopausal women did not carry the threat of menstrual blood with them in ritual either. This is manifest in the annual harvest ritual of Dipri, celebrated by the Abidji and Adioukrou of Côte d’Ivoire. During the festival, young initiates gather at the river and are overcome with the genie’s spirit, sending them into a frenzied trance that can only be halted when they wound themselves. Menstruating women are prohibited from attending for fear that their blood might impede the healing of young initiates’ ritual stab wounds (Grillo 2018). Whilst they are perceived as dangerous in this way, older women cleanse and protect the village from danger the night before Dipri in the ritual of egbiki, an exclusive and nude parade in which women chant, pound their pestles on the ground and expel any evil present. Significantly though, menstrual blood is widely regarded as potent as much as it is an impurity: hence, the Asante King’s golden stool would be ritually washed with menstrual blood to sanctify it (Akyeampong and Obeng 1995). It will become apparent that, like menstruation, menopause and postmenopausal women were regarded in ambivalent terms. Nevertheless, the cessation of menstruation is a significant characteristic of the menopause, and one which granted older women prestige.

Passing the menopause was also a natural cue for women to widen their focus from the family to the wider community, taking on the role as mothers for the whole village. This is a further reason why certain positions were exclusive to postmenopausal women. For instance, the Igbo women’s assembly (ikporoani) was headed by the longest-married woman (Coquery-Vidrovitch 1997), whilst their female chief (omu) was a senior woman of high repute, sometimes the oldest daughter of a lineage. Also amongst the Igbo, age-grade and title societies ranked older women in positions of great influence on important decisions (Chuku 2009). As well as the more political roles such as these, the menopause qualified women to take on certain active roles in their communities. In French Sudan, modern-day Mali, women began to practice as midwives only after passing the menopause. One prenuptial ritual specialist, a magnamagan, described that:

After the age of forty, [women] teach the profession of magnamagan to their daughters and they exercise the profession of midwife starting about the age of forty-five or fifty, after the menopause.

Aoua Kéita, Femme d’Afrique (Paris: Présence africaine, 1975), 276-279 cited in Turrittin, “Colonial Midwives,” 84.

Older women, having likely had more children themselves, would have been regarded as more experienced and qualified to assist at births. But, according to this magnamagan, it was also because “a woman no longer menstruates and is normally no longer obliged to be occupied during the night” (Kéita 1975: 267-279). The fact of being postmenopausal widened the sphere of a woman’s influence, as well as her responsibility.

Another reason sometimes offered for the respect given to postmenopausal women was their supposed masculinity. As historian Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch described: “Menopause made women asexual, in a sense, and thus similar to men” (1997: 36). This presumes, firstly, that femininity is solely dependent on the ability to bear children. It also sits far too safely in the presumption that power is inherently masculine and can only be wielded by masculine figures. Yet, Coquery-Vidrovitch is right in her observation that the menopause affected women’s perceived gender. Various instances crop up wherein postmenopausal women are referred to in ambiguous gender terms, either embodying a dual gender, or none. The Yoruba, for instance, describe female elders as abâra méji (“owners of two bodies”), as well as oní l’oní aiyé (“owners of the world”) (Grillo 2018: 44). High-ranking older women often wore regalia similar to that of high-ranking men, including the formal dress of the Igbo’s omu (Chuku 2009) and the Queen Mother (iyoba) of Benin (Kaplan 1993). The most frequently depicted woman in the art of the royal court, the postmenopausal iyoba was also always portrayed androgynously. Such is the case in the 18-19th century altarpiece below, which features a central iyoba surrounded by female attendants, demonstrating the degree to which Queen Mothers were revered in the Kingdom of Benin (see Figure 4). The most frequently depicted woman in art of the royal court, the postmenopausal iyoba was also always portrayed androgynously. Furthermore, in the Oyo kingdom of the Yoruba, a senior woman called the yamode who attended to the king’s (alafin’s) spiritual needs would be referred to by him as baba (“father”) (Coquery-Vidrovitch 1997). Perhaps it is not insignificant, therefore, that a number of peoples referred to a supreme being in dual gender terms, including the Asante, the Kuiye of Batammaliba in Togo, the Ewe in Ghana and Benin and the Yoruba (Ebere 2011). Existing beyond the limits of defined gender, postmenopausal women were freer and distinguished, and perhaps even closer to the spiritual realm.

The Trunk of Postmenopausal Prestige: Matriliny, Matriarchy and Moral Authority

Upon these three fundamental characteristics of the menopause – the stopping of menstruation, the broadening of social responsibilities, and a perceived gender ambiguity – traditions of reverence and respect to older women became established. Two of these traditions have come to be viewed in close association: matriliny (the tracing of ancestral descent through the female line rather than the male, as is the presiding custom in Europe and the West) and matriarchy. Various hypotheses exist as to the origins of these in West African societies, and across the continent as a whole. One plausible theory from Camila Power and Christopher Opie suggests that prehistorically, women were based around their postmenopausal mother because her foraging and gathering made up the calorie deficit of a woman with young children (not conceived by a single male partner) (2009). Still, whether matriliny preceded matriarchy, or vice versa, could come down to a ‘chicken and the egg’ scenario, and although they are mutually reinforcing, they do not exist uniformly throughout the region. At different times, patriarchal influences have interfered with their applications to varying degrees, so that in some places neither are evident, but “matrifocal principles” exist nonetheless (Olupona 1991 cited in Bádéjo 1998: 95). As building blocks of West African society, matriliny and matriarchy are both testimonies to older women’s deep-rooted pre-eminence.

To add to these is a further tradition across West Africa of a belief in the ultimate moral authority of postmenopausal mothers. This moral say-so, the ability to distinguish good from evil, and to dispel malevolent forces, is based upon a fundamentally female and maternal power, but is without the ‘vulnerabilities’ of being fertile. This is why, in the main ritual expression of older women’s moral authority, it is they who take the ritual to its furthest reaches, whilst any younger women participating stand respectfully back. Though known by various names throughout the region, this ritual (egbiki to the Abidji in Côte d’Ivoire, momome or mmobomme to the Asante and adjanu to the Baulé, to name a few) intends to spiritually cleanse the community by expelling evil and threats; whereas in the pre-colonial period it mostly targeted disease, conflict and witchcraft, it has since been used more publicly in protest. Allowing for regional variations, its participants generally proceed through the village partly or completely nude, chanting and cursing, brandishing pestles or vines, and slapping their breasts and genitalia. The women may also defecate, urinate and crouch in the childbearing position – all to condemn, and hopefully disperse, the perceived evil at hand (Boni 2008 and Grillo 2018). This powerful ritual is a vivid representation of the moral authority associated with postmenopausal female elders, a position which invites ambiguity and, at worse, attack.

Ambivalence towards the Authoritative

It will come as no surprise to most that older women’s roles were threatened and challenged by the twentieth century’s many changes, particularly the heavy influence of European colonialism with its undisguised patriarchal tendencies. Under this rule, postmenopausal women were immediately disadvantaged, supplanted and ignored. The historical position of the female elder as “guardian of morals and of harmony” in the community, however, laid them particularly open to attack when new and numerous threats were perceived (Fortes 1950: 276).

Coupled with the ambiguity of gender associated with the menopause, older women also resided in an ambiguous moral grey area as the ones with moral authority, embodying both good and evil. Consequently, when witch-finding movements swept across West Africa from the beginning of the century, older women were disproportionately the targets. It is often stated that African ‘witches’ can be female or male and of any age – though this is true, accounts such as that by David Tait of the Dagbon kingdom of northern Ghana in the 1950s found that the accused witches “were all middle-aged to old women and only one carried a baby on her back” (1963: 137). Indeed, in some West African languages, ‘old woman’ and ‘witch’ are synonymous: the Dagomba call witches pagkura, which means “old woman” (Tait 1963: 138), and one term amongst the Yoruba is ìyá wa, “our Mothers” (Apter 1991: 222). Even a colonial commissioner in Ghana noted in 1913 that “It is peculiar that nearly always old women assume these forms of evil spirits,” by which he meant shape-shifted creatures (Nash, in Zouarugu Informal Diary 1913, cited in Parker 2006: 371). Writing about the ambivalence often felt towards hyenas and their frequent embodiment of witches, John Parker remarked that the association could partly be due to the “perceived hermaphroditism” of the female Spotted Hyena, which has a “pseudo-penis” and “pseudo-scrotum” (2006: 370). Given this, it is hardly surprising that the older woman, perceived as ambiguously gendered and a potential witch, would be thought to adopt the hyena as her shape-shifting animal of choice.

That which added to postmenopausal women’s prestige, their moral superiority, could also therefore make them vulnerable during times of anxiety. However, it is of note that one of the major anti-witchcraft movements in early twentieth century Ghana was called Aberewa, meaning “The Old Woman” (Parker 2004). Although many of its targets were still older women, in being called Aberewa it appealed to the potency traditionally associated with them and historically called upon to protect society. It was not exclusively a condemnation, nor an accusation, so much as a plea. As is often true of the most fundamental things in life, the pre-eminence of postmenopausal women was, and is, steeped in contradictions.

Older women historically held positions of influence in West Africa not just on the grounds of age as ‘superior matriarchs’, but specifically due to characteristics of their postmenopausal state. The end of menstruation, the capacity to broaden their social responsibilities and the perceived ambiguity of their gender were all fundamental effects of this stage in women’s life which carved out a unique, prestigious position for them. Given the ancientness of this biological change and its effects, the traditions of matriliny, matriarchal structures and moral authority have grown up closely entwined with the roots of their pre-eminence. On this steady bedrock of menopausal significance, older women often had influential roles in society, politics and the ritual realm. Though their roles have been threatened and, at times, extinguished, this bedrock is unshaken.

Citations

Aidoo, Agnes Akosua 1977. “Asante Queen Mothers in Government and Politics in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 9(1): 1-13.

Akyeampong, E. and Obeng, P. 1995. “Spirituality, Gender, and Power in Asante History.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 28(3): 481-508.

Apter, Andrew 1991. “The Embodiment of Paradox: Yoruba Kingship and Female Power.” Cultural Anthropology 6(2): 212-229.

Boni, Stefano 2008. “Female Cleansing of the Community. The “Momome” Ritual of the Akan World.” Cahiers d’Études Africaines 48(192): 765-790.

Buckley, Thomas and Gottlieb, Alma 1988. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Chuku, Gloria 2009. “Igbo Women and Political Participation in Nigeria, 1800s-2005.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 42(1): 81-103.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, Catherine 1997. African Women: A Modern History. Colorado: Westview Press.

Ebere, C. 2011. “Beating the Masculinity Game: Evidence from African Traditional Religion.” CrossCurrents 61(4): 480-495.

Fortes, Meyer 1950. “Kinship and marriage among the Ashanti.” In African Systems of Kinship and Marriage, edited by A. R. Radcliffe-Brown and D. Forde. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grillo, Laura S. 2018 An Intimate Rebuke: Female Genital Power in Ritual and Politics in West Africa. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Kaplan, Flora S. 1993 “Iyoba, The Queen Mother of Benin: Images and Ambiguity in Gender and Sex Roles in Court Art.” Art History 16(3): 386-407.

Opie, Kit and Camilla Power 2008. “Grandmothering and Female Coalitions: A Basis for Matrilineal Priority?” In Early Human Kinship: From Sex to Social Reproduction, edited by Nicholas J. Allen et al.,168-186. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230002253_Grandmothering_and_Female_Coalitions (accessed November 8th, 2020).

Parker, John 2004. “Witchcraft, Anti-Witchcraft and Trans-Regional Ritual Innovation in Early Colonial Ghana: Sakrabundi and Aberewa, 1889-1910.” The Journal of African History 45(3): 393-420.

Parker, John 2006. “Northern Gothic: Witches, Ghosts and Werewolves in the Savanna Hinterland of the Gold Coast, 1900s-1950s.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 76(3): 352-380.

Rattray, R. S. 1929. Ashanti Law and Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tait, David 1963. “A Sorcery Hunt in Dagomba.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 33(2): 136-147.

Van der Geest, Sjaak 1998. “Opanyin: The Ideal of Elder in the Akan Culture of Ghana.” Canadian Journal of African Studies 32(3): 449-493.

Amelia Storey

she/her

Having returned to SOAS after two years as a gardener in an intentional community, I have recently graduated with a BA in History. My interests lie mainly at the intersections of gender history and the history of religion and belief, particularly in Africa.

SOAS History Blog, Department of History, Religions and Philosophy, SOAS University of London