Active Students or Unaware Workers?

By Eva Herman. Eva studied the MSc in Labour, Social Movements and Development at SOAS part-time from 2013-2015. She now works at Middlesex University, assisting the Unpaid Britain research project, which investigates unpaid wages in Britain, and is funded by the Trust for London. The research project has a blog, which includes findings and reflections. The project can also be followed on Twitter and Facebook. The views expressed in this article are Eva’s own, and don’t necessarily reflect the views of the SOAS Department of Development Studies.

I chose to study Labour Social Movements and Development (LSMD) at SOAS after completing an undergraduate degree in Development Studies at the University of East Anglia. This course was, for me, the natural next step as throughout my undergraduate degree I discovered the most important thing to understand when it comes to development, economics or politics is work and change. As capitalist development has spread people have become increasingly dependent on work in order to survive. This spread of capitalism, however, has not come without altercations; the only way changes have occurred is through movements, as workers fight to better their conditions of work.

Throughout the course we learnt about how structures, processes and patterns of labour/work changed and were developed over time. We started to understand the conflict that lies at the heart of this process and capitalism – the conflict between capital and labour. This conflict in essence stems from the need for capital to constantly make a profit (accumulate) and to maintain its competitive edge, while simultaneously the social cost of labour increases as workers fight for their rights and improved working conditions that in turn erode ‘the basis of capital accumulation’ (Chang 2009:163). To deal with this conflict, and avoid the increasing social costs of labour, capital needs to invent new mechanisms and regimes of production. This process is what Chang (2005) calls the movement of capital. It implies not only the physical movement but also changes made in mechanisms of production and technology (Silver 2003 and Chang 2009). Hence we learnt how this process occurred over time globally, regionally and locally.

Throughout this learning process we debated and discussed the different issues. Everyone brought different perspectives and ideas forward. We were encouraged to think for ourselves and develop our own arguments and ideas. We were also encouraged to be active, and to think and develop campaigns to fight for better rights for workers. This was encouraged through the course as we developed a campaign (our group was based on Domestic Workers Movements in the UK), as well as being active in SOAS-wide campaigns for the cleaners. We joined our lecturers on picket lines when they were on strike, and wrote letters and petitions to the vice chancellor in support of all the staff at the university. We did all of this without ever once looking at ourselves and considering our own identity, situation and rights as workers, or where and how we fitted in in the whole process.

Many of the students that I studied with including myself worked in order to be able support themselves through their studies. I worked both during my undergraduate (as a health care assistant and doing promotion) and as a postgraduate (as a waitress). I never, however, knew what my rights were as a worker; I knew I should be paid minimum wage but that was about it. I also never really looked into what my rights were; this was partly due to not seeing myself as a worker as work was not my main activity. On the other hand, I trusted that my employers knew the law and felt like they were doing me a favour by employing me in the first place. I was not the only one – as the postgraduate representative for Law and Social Sciences at SOAS, I had a few students come up to me and ask how they could get extensions as they could not afford to have time off work to complete assignments. One of the students who asked me about this said that they had asked their employer whether they could get paid leave to do their exam, to which the employer replied ‘we are not a charity, are you trying to fleece us dry? You are a part-time worker and not entitled to holiday pay.’

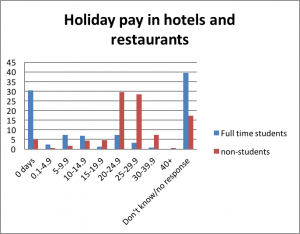

Students’ lack of awareness regarding their rights at work, especially when it comes to holiday entitlements, is not uncommon, so much so that certain employers and sectors may employ students specifically to get their competitive advantage. I now work at Middlesex University as a research assistant investigating unpaid wages in the UK. One aspect of non-payment that we are interested in is the non-payment of holiday pay. An investigation into the Labour Force Survey (LFS) found that 3.7% of the workforce are full time students. They are, however, concentrated in certain sectors: food and beverage services activities (SIC 56) has the highest proportion of full time students, with 19.9%; second is sports, amusement and recreation (SIC 93), with 15%; and third is retail (SIC 47) with over 11%. For the purposes of this blog we will focus on hotels and restaurants as the majority of students in full time education work in this sector (56%). When it comes to payment or non-payment of holiday pay a very interesting pictures appears. It shows that 30.4% of full time students received no days of holiday pay and 39.4% of students didn’t know if they had received holiday pay or did not respond to the given question. This is even more shocking when compared to those who are not in full time education. Only 5% of these received no holiday pay. 17% didn’t know if they had received holiday pay or did not respond to the given question. 30% received between 20 and 25 days holiday pay and 29% received between 25 and 30 days paid holiday (see graph below). This, in essence, shows an indication of lack of awareness of students, but also how employers are able to take advantage of them.

Key informants of the Unpaid Britain project revealed that some employers run a ‘don’t ask don’t get’ policy when it comes to the payment of holiday pay. Hence the employment of students who are often unaware of their rights at work and who may not see themselves as workers is an important mechanism for employers in certain industries to maintain a competitive edge. The project recently developed an Index of Employer Delinquency which measures which sectors are the most exploitative; the food and beverage service activities appears second on this index.

I still maintain that when it comes to development studies the most important thing to understand is work and change. What I have learnt from this whole experience, however, is that not only do we need to understand the mechanisms and processes that are happening around us, but we should also be aware of how we fit into them. As long as students stay unaware of their own rights and don’t see themselves as workers, sectors such as the food and beverage service activities will remain exploitative, as they will never be challenged. So what we need to learn from this is the next time an employer tells us students, ‘No, you do not get paid leave’, we will have to say that we know full well that by law we do!

References

Chang D., 2009. ‘Informalising Labour in Asia’s Global Factory’, Journal of Contemporary Asia 39(2), pp. 161–179.

Chang, D., 2005 ‘Global Supply Chain and the World of Capitalist Work’, Asian Labour Update 54, pp. 1-11.

Silver, B. J. 2003. Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization since 1870, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.