Our Work – Activism, Art, Research – A blog on Kashmiri Half Widows by MA Student Niharika Pandit

CGS MA student, Niharika Pandit, has put together a project for her Gender, Armed Conflict, and International Law module. The project, on the topic of half widows in Kashmir, is in the form of a live blog with sections arranged like that of an essay. However, it will be more interactive, beginning conversations on research, art, methods, and activism. Visit the project here.

About this project

This blog is an attempt to understand the resistance and struggles of Kashmiri half-widows against the backdrop of Kashmir insurgency through the available academic and popular literature while also engaging in a feminist legal analysis of the United Nations Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. By centralizing half-widows in this military conflict,[1] I aim to enquire into how some women are rendered invisible in the law and to be visible means ascription of a victim status to them thereby, undermining their resistive agency.

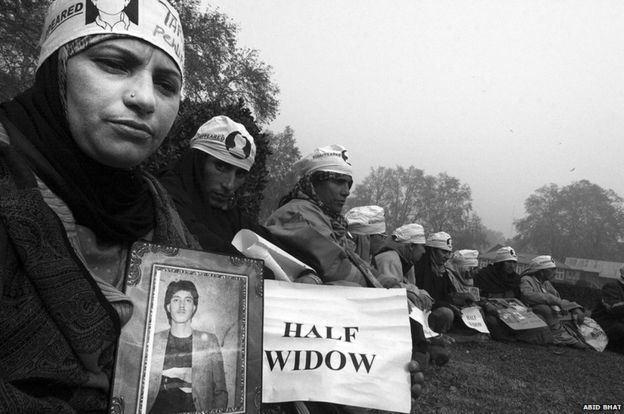

Who are Half-Widows?

Half-widows are those women “whose husbands have disappeared but not yet declared dead. Such disappearances have been carried out by government forces—police, paramilitary or army—or by militants”.[2]These women are neither considered married because of the absence of their husbands nor widows, as there isn’t any evidence confirming their husbands’ death thus, situated in a very ambiguous, legally unrecognized and a metonymic category of half-widows.

While it is beyond the scope of this project to go into detail about the political decisions that followed India’s independence from the British rule, dividing the subcontinent into Muslim-majority Pakistan and secular India with temporary accession of Jammu and Kashmir to the Indian Union and the rise of armed resistance in Kashmir in 1989,[3] the struggle of half-widows cannot be seen in isolation with the wider resistance pertaining to the territorial dispute of the Kashmir Valley.[4] In fact, the struggles of half-widows came to the fore after 1989 insurgency following which it is estimated that at least 70,000 people had died while more than 8,000 were involuntarily or enforced disappeared by the Indian military forces till 2009.[5] As per Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), independent collective comprising relatives of those who were enforced disappeared, the majority of people who have been picked up include men, minors and people of all ages.[6]Thus, revealing the gendered nature of this human rights violation where half-widows among other women—mothers, daughters, sisters, male relatives and children have been left behind to fend for themselves and their families in a highly gender-segregated, structurally unequal Kashmiri society.[7] This simultaneously makes many half-widows more visible as they step out of their house to find work, protest demanding state accountability while also on a constant search for their disappeared husbands, and invisible because they are neither wives nor widows, situated in an abstruse space. The performative agency[8] of these women as they step out of the house to find work to support their families, demanding the state’s accountability while diving into untested waters like army camps, detention centers, problematizes the strict binaries of public/private, visible/invisible. Such a blurring of the binaries is also evident in how half-widows, who belong to a hierarchically invisible gender category become visible when their husbands disappear, a theme which anthropologist Ather Zia has developed in her monograph of a half-widow[9]. Some such themes will be explored throughout the blog with an additional legal lens.

Among other demands of APDP and half-widows includes India’s ratification of the United Nations Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances[10], an international legal instrument adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 20, 2006 and came into force on December 23, 2010. Article 5 of this international legal instrument categorizes widespread or systematic practice of enforced disappearance as a crime against humanity.[11] Although India signed the convention on February 6, 2007, it hasn’t ratified the same which indicates a lack of willingness on its part to prosecute enforced disappearances and formally begin a post-conflict process.[12]

For the purpose of this project, I will focus on Article 24 of this international legal instrument, which specifies the ‘victims’ of enforced disappearances thus, widening its scope to acknowledge and understand the harm suffered by relatives of the disappeared while making them eligible for compensation, rehabilitation, restoration of their dignity, reputation and guaranteeing non-repetition. However, I will argue that the status of Kashmiri half-widows in the international law remains that of secondary victims, dependent on and determined by the return of their husbands. Half-widows, both in conventional and customary international law remain legally unrecognized and are never treated as isolated victims.[13] I take exception to this victim narrative as well which is also employed in the Women, Peace and Security resolutions and advocated by some international feminists like Catharine MacKinnon to argue that introducing a homogenous universal victim for women in the legal discourse closely resembles the western liberal project[14] where gender identity is assumed to be the focal point of discrimination while racial, age, sexuality, religion, class-related subjectivities remain underemphasized. In a quest to identify a common global subject within this victimization narrative, the differences between men and women are assumed prior to their entry into social relations.[15] However, the case of Kashmiri half-widows is further complicated by even their secondary status in this victimization rhetoric therefore, a half-widow is never fully acknowledged as a subject on her own in the international law leading one to question whether she, the subaltern can ever speak?[16] For such an analysis I will employ tools of deconstructionism, critique of victimization rhetoric while using Spivak and Kapur’s postcolonialism to speak to the law and question how the law presupposes certain subjects and who is rendered invisible. While I also acknowledge that the victim rhetoric can be deconstructed using a sexuality lens by arguing that such categories are implicitly heteronormative but for this project, due to available evidence in academic and popular literature, I will operate within the gender binary.

It is important to acknowledge that in the context of Kashmir the postcolonial moment needs to be complicated to incorporate contradictions and plurality of experiences, presence of several public spaces[17] because of heavy militarization by India, a former British colony and now the belligerent, in Kashmir. Kashmiri half-widows are thus, different from Spivak’s imagination of a postcolonial gendered subaltern subject because of the geopolitical considerations mentioned above. This does not mean that that a Kashmiri half-widow is a more authentic subaltern subject, such an assertion would qualify as an essentialist trope that Spivak warns us about. Instead, it is important to deconstruct the half-widow and her subalternity to prove the heterogeneity of a colonized subaltern subject[18] while also establishing that the Kashmiri half-widow does not represent the impact of militarization on women in Kashmir and that women experience conflict differently.[19]

[1] Seema Kazi, Between Democracy & Nation Gender and Militarisation in Kashmir (Women Unlimited 2009) p.136.

[2] Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), ‘Half Widow, Half Wife?: Responding to Gendered Violence in Kashmir’ July 2011. Accessed March 15, 2016.

[3] AnanyaJahanara Kabir, Territory of Desire Representing the Valley of Kashmir (The University of Minnesota Press 2009) p.1-27.

[4] Deya Bhattacharya, ‘The Plight of Kashmiri Half-Widows’ 2016. Accessed March 15, 2016.

[5] Angana Chatterji and others, Buried Evidence 2009. Accessed March 25, 2016.

[6] Supra note 2

[7] Supra note 4

[8] Judith Butler, ‘Performative Agency’ [2010] 3(2) Journal of Cultural Economy <10.1080/17530350.2010.494117> accessed 27 March 2016.

[9] Ather Zia, ‘The Spectacle of a Good-Half Widow: Performing Agency in the Human Rights Movement in Kashmir’ [2013] UCLA Centre for the Study of Women <http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xx4n1zf> accessed March 23, 2016.

[10] Email interview with Omaid Nazir, Project Manager, APDP.

[11] ‘Convention CED’ (Ohchr.org, 2016) <http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CED/Pages/ConventionCED.aspx> accessed 22 March 2016.

[12] Supra note 4 at 47

[13] Supra note 4

[14] Ratna Kapur, Erotic Justice Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism (The Glass House Press 2005) p.94-136.

[15] Chandra Talpade Mohanty, Feminism Without Borders (Zubaan 2003) p.26.

[16] GayatriChakravorty Spivak, Can the Subaltern Speak?. in RosalindC Morris (ed), Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea (Columbia University Press 2010) p.28.

[17] Supra note 3

[18] Supra note 16

[19] Supra note 1

Note: All photographs featured on this blog have been reproduced following permission by APDP and photographer Abid Bhat.