China’s BRI in Israel-Palestine - SOAS China Institute

China’s BRI in Israel-Palestine: Geo-economic opportunities and geopolitical uncertainties

By Jacinthe Nourrit | 07 September 2021

要想富先修路 : To become rich, one must first build roads.

一山不容二虎 : A mountain cannot accommodate two tigers.

– (Chinese proverbs)

The BRI envisions the revival of the ancient Silk Road by upgrading Eurasian trade routes under foundational values of ‘win-win results’ and ‘peaceful coexistence’. In 2016, China recalibrated its foreign policy with the Arab pivot. However, abrasive dynamics make the region a risky investment destination. The Israel-Palestine protracted sovereignty dispute clashes with BRI ideologies of a purely geoeconomic and apolitical project.

The PRC’s increasing influence in regional politico-security spheres to protect its overseas commercial assets, entailing enhanced peacebuilding efforts and strategic balancing to build regional resilience are at odds with the constitutional principle of non-interference. Additionally, Chinese encroachment in local affairs may provoke frictions with the US as the traditional conflict mediator.

Novel foreign policy doctrine

Since the ‘century of humiliation’, China’s international posture has globalised, evolving from a peripheric role, strictly enforcing a Westphalian interpretation of territoriality and other countries’ sovereignty to become fully integrated in global economics. President Xi’s assertive leadership, military build-up and economic diplomacy have cemented an international influence, connecting with politically unstable governments in MENA for BRI projects.

The Arab pivot was formalised as an independent economic policy, alongside political considerations, igniting a renewed foreign standing. The geoeconomic strategy blames socioeconomic stagnation as the cause of regional insecurity and perceives the improvement of living standards as a solution. This ‘people’s livelihood governance’ approach to conflict mediation constitutes China’s developmental peace agenda, diverging from neoliberal growth recommendations.

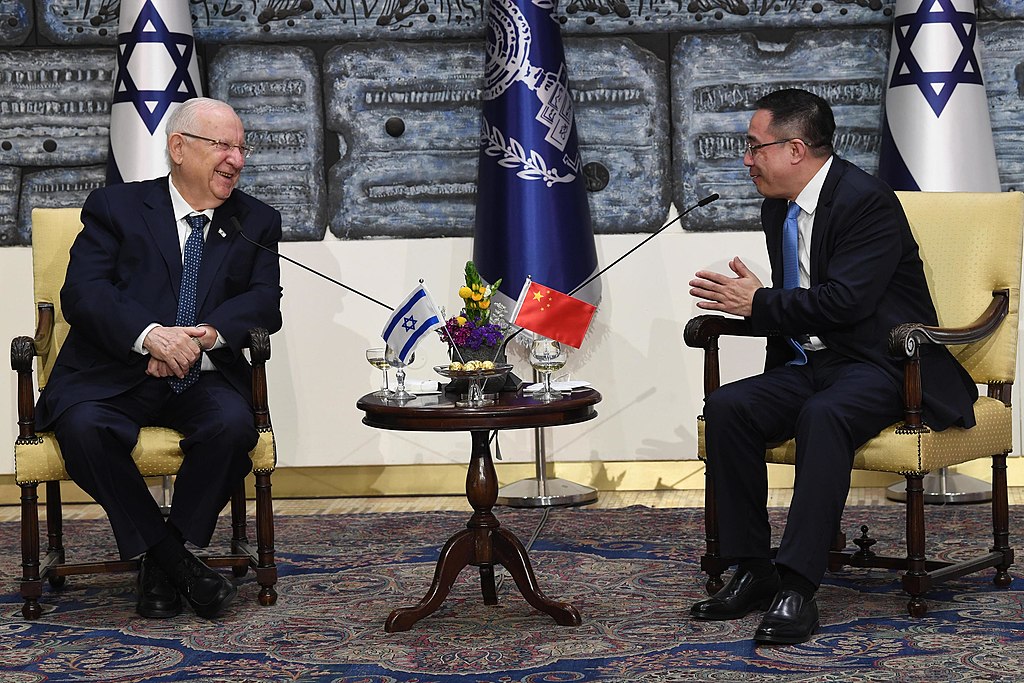

The ‘Chinese-style mediation diplomacy’ bears far-reaching geopolitical implications in Israel-Palestine. In its willingness to unilaterally conduct conflict resolution via development, Beijing’s peacebuilding instruments range from: successive peace proposals, an appointed Special Envoy, UNTSO peacekeeping forces and a peace forum.

The PRC’s ambitions with the BRI and the Arab pivot are multifold: to spur domestic economic growth and international competitivity to fulfil the centennial goals by 2049. Since accession to power, Xi’s use of both classic and novel philosophical concepts in official rhetoric has transformed Chinese citizens’ self-perceptions into asserted and patriotic national identities. Consequently, government reforms were backed by public consensus and Xi endorsed responsibilities of international governance in a distinct foreign policy doctrine enshrining Chinese exceptionalism: ‘major country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics’ (中国特色大国外交), establishing overarching support for long-term global geoeconomic expansion and philanthropy in MENA, accompanied by both cooperative and coercive power projections.

The Arab policy and the upgraded self-identity contribute to the portrayal of China as a dependable economic partner and diligent political ally. It is against the backdrop of a moribund Oslo process and shattered US credibility in peace mediation that China has been offering brokerage in the Israel-Palestine peace process.

Local implications

China’s economic diplomacy in Israel-Palestine has yielded multiple occasions to showcase political influence. The BRI and associated economic instruments should contribute to advancing both peoples’ welfare and economic prosperity. Politically, China’s conditionality-free economic statecraft and ‘quasi-mediation diplomacy’ inherently rules out military intervention. Benefiting from its impartiality as an external actor of non-Abrahamic faith, Beijing has befriended all political factions including Hamas to promote its consultative methodology for conflict resolution, resulting in a widening of the channels of influence.

Regional activism is developing around a China-led security paradigm including GCC countries, intending to initiate political dialogue by creating interdependencies. As a combination of eco-security incentives for peace, the BRI should allow China to become a political stabiliser.

Nevertheless, geoeconomic setbacks do persist: the ‘mutual growth’ argument may lack transferability in a conflict zone. China’s trade and investment volume with Palestine represents a meagre fraction of China-Israel commercial relations: US$88,7 million for the former against US$16,2 billion for the later. The dramatic discrepancy is likely to widen with China pursuing high-tech ventures in Israel.

Political challenges have emerged within China’s ‘partially detached’ mediation style, remaining an absentee in regional conflicts due to its non-interventionist guideline. Beijing’s risk aversion has hitherto resulted in deflection strategies creating a veil for inaction. The tenuous peace plans, the lack of coherent policy and deliverable solution, a weak regional political leadership with a reluctance to entangle may hurt China’s image as a reliable peace stakeholder.

Factually, the BRI lacks a salient security dimension including a tangible anti-terrorism apparatus to address Israel-Palestine’s endemic hurdles. China for now remains in the shadow of the American regional security umbrella. These structural limitations compromise Xi’s peace activism. Beijing’s posture as a construction contractor and an international dispute mediator is inconsistent with its constitutional values. The costs of political leadership could outweigh economic benefits with possibilities for geopolitical tensions and big power rivalry.

The Palestine-Israel Peace Symposium (巴勒斯坦以色列和平人士研讨会)

On 21-22 December 2017, China convened a shuttle diplomacy initiative for regional dialogue, resulting in the production of non-binding measures under two-state solution principles.

The symposium was aimed at facilitating China’s positioning as a stabilising force in conflict settlement with a pragmatic approach toward constructive engagement, creating a platform for neutral third-party stewardship of direct negotiations and exploration of new peace channels.

Leveraging its direct relationship with both parties to conduct trust-building, its non-interventionist posture and unobtrusive diplomatic culture, China has deliberately avoided agenda-setting. Concurrently, the symposium remains a tamed attempt at conflict resolution. Peace summitry producing solely symbolic measures remains an inchoate endeavour.

International reactions have predominantly been negative: media reports display scepticism at Chinese peacebuilding by openly discrediting the initiative or diverting the attention toward the UN vote against Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s undivided capital the same month.

Projections

Xi’s commitment to convene future summits denotes further engagement in the Israel-Palestine peace process. Howbeit, substantial prerequisites remain for China to become a diplomatic influencer:

- Formulation of a pro-active foreign policy to effectively participate in security governance.

- Engagement in trust-building via knowledge expansion on Israeli and Palestinian civil societies.

- Support of a ‘whole-of-region diplomacy’ beyond the economic angle to constructively participate in peacebuilding and civilian-led social engineering.

- Institutionalisation of the symposium with an annual scheduling and rallying of the international community for political consultation, collective problem-solving and transparency.

- Alignment of Sino-US priorities, methodologies and policies in MENA under a common framework. The complementarity of commercial and political interests allows compatibility for great power cooperation. A Middle-Eastern eco-politico-security governance alliance would be less contradictory than in the Asia-Pacific.

As a vehicle for China’s economic diplomacy and west-looking foreign policy, the BRI creates a platform for the Arab pivot and Beijing’s economic statecraft under the developmental peace paradigm. By mutating the original geoeconomic project into a geopolitical engine, Xi’s regional strategic activism elevates China as a conciliatory force and active referee in peace negotiations. Nonetheless, added to the doctrinal challenge, ambitions have yet to be matched with tangible roadmaps.

The BRI does require a new approach to local politics in order to produce sustainable peace spill-overs in Israel-Palestine. A new conceptual policy for conflict resolution should include a reform of China’s diplomatic posture, amending the non-interference doctrine with an emphasis on political agency.

Beijing’s engagement should be holistic: spanning across the economic, political and security dimensions and utilise the Westphalian culture to act toward becoming a fulcrum for regional stability. These measures would stimulate China’s peace-making capacity, match lofty aspirations with actionable steps and boost diplomatic outreach in the Middle East. The economic strategy of infrastructure building to unleash influence may be effective but the political dimension must be borne in mind to reify Pax Sinica and access regional and global governance. It remains to be seen whether the developmental diplomacy and subtle political presence will propel China to our world’s mountain top and crowd Washington as the incumbent peace broker out.

Jacinthe Nourrit is a strategy and public policy consultant, specialising in education, social and foreign policies. Formerly, she has worked in diplomacy at the French embassy in Israel and China. She holds a Masters of English and American Studies from the University of Montpellier / University of Birmingham and a Masters of International Studies and Diplomacy from SOAS.

The views expressed on this blog are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of the SOAS China Institute.

SHARE THIS POST