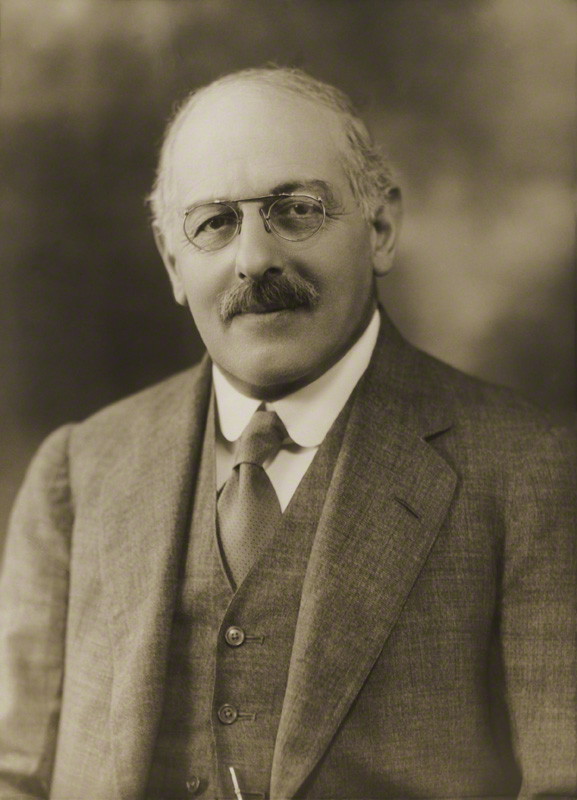

Sir Philip Hartog: Remembering SOAS’s forgotten founder

Sir Philip Joseph Hartog (1864 – 1947) has now become the largely forgotten founder of SOAS after he campaigned for the parliamentary committee to consider starting an Oriental school in London. Even in the face of cynicism from Oxbridge wigs and crippling underfunding Hartog still managed to see the future of the school beyond being a post-war language training arm of the University of London. While the government was only concerned with instructing foreign officials in the language and cultures of the place they would be working, Hartog was planning for a legacy much wider than anyone had anticipated.

Philip Joseph Hartog was born in London in 1864 and educated at UCL and Owens College Manchester. He was an assistant lecturer in chemistry in Manchester until 1903 when he left to become registrar at the University of London.

He published a string of books in the 1930s which revealed an obsession for school administration: A Conspectus of Examinations in Great Britain and Northern Ireland (1938), The Purpose of Examinations (1938), The Marking of English Essays (1942) and a sure fire favourite, An Examination of Examinations (1935). Although Hartog was a keen Chemist, science was not where his future lay.

As his wife recalls in P.J. Hartog: A memoir, his dedication to the establishment of an oriental school outstripped his “personal comfort and ease”. After hearing about the opportunity to put forward a proposal he cut short his holiday, returned to London and worked around the clock for days on end to submit a report on the post-war need for trained linguists.

Cambridge was particularly opposed to establishing a school in London and deemed “the whole thing a waste of public money”. It was obvious that they believed the existence of a language training centre in the capital would jeopardise their own security and draw talent, funding and students away from them. But ever the optimist, Hartog said these comments were born of a “subterranean jealousy which the authors will be somewhat ashamed to display openly.” And he was correct. There were never any formal interventions, just the tittle-tattle of naysayers and the whispers of pessimists.

He was the only permanent member of the governing body who seen the School through from inception to opening, with many academics working part-time because funds initially did not stretch to hire all staff on full-time contracts.

It is commonly acknowledged that he declined the role to be SOAS’ first Director, advising that a scholar must take the position before him – which led to the election of Sir Edward Denison Ross.

Although his time in London was beneficial to the new languages school in Finsbury Circus, all this was merely a forward to the next chapter in his life. Hartog went on to become the first vice-chancellor of Dhaka University in 1920. He was heavily involved in the colonial education system in India and got into a public furrow with Gandhi over Britain’s meddling in Indian schools.

Hartog was appointed to the Auxiliary Committee on Education and published a report on the quality and progress of Indian education. His contemporaries congratulated him on demolishing the prejudices his predecessors had for the local education system, but many Indians saw it as a scathing criticism.

Emerging from the tyranny of colonialism, history paints education as being a positive legacy of the British Raj. In 1931, however, Gandhi said “today, India is more illiterate than it was fifty of a hundred years ago” since the British took the seat of power.

To someone like Hartog, who had made the development of education his life’s work, he was outraged at Gandhi’s remarks. Hartog attempted to keep up correspondence with Gandhi even during his imprisonment the following year, but obvious circumstances prevented Gandhi from engaging in proper scholarly debate. Now with little public opposition, Hartog gave lectures in India and London expounding the improvements the British government had made to indigenous education. So perhaps a myth was sown.**

Sir Philip Hartog was an educationalist, a reformer, a visionary and dedicated worker. He died age 84 in London with an obituary describing him as having “long-sighted shrewdness and almost missionary enthusiasm”.

**The Beautiful Tree by James Tooley, page 220

Good Teacher Names Web Of Science Quick Search

my web-site – pdf wordpress

Love the site– really individual pleasant and great deals to

see! https://ketorecipesnew.com/

Simply desired to stress I am just pleased I happened in your

web page. http://ketodietione.com/

Your posts is amazingly unique. https://ketodietplanus.com/

Many thanks extremely practical. Will share website with my friends. https://onlinedatinglook.com/