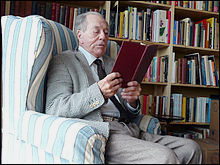

Professor David Llewelyn Snellgrove (29 June 1920 – 25 March 2016)

Professor David Snellgrove, a leading SOAS scholar of the religion, languages and history of Buddhist India and Tibet, died earlier this year aged 95. He joined SOAS in 1950 and made a major contribution to Tibetan and Buddhist studies. Dr Tadeusz Skorupski, Emeritus Reader in the Department of Religions and Philosophies at SOAS; Cathy Cantwell, Associate Faculty Member, Oriental Institute, University of Oxford; and Francesca Fremantle, scholar and translator of Sanskrit and Tibetan works, share their stories of

Professor David Snellgrove, a leading SOAS scholar of the religion, languages and history of Buddhist India and Tibet, died earlier this year aged 95. He joined SOAS in 1950 and made a major contribution to Tibetan and Buddhist studies. Dr Tadeusz Skorupski, Emeritus Reader in the Department of Religions and Philosophies at SOAS; Cathy Cantwell, Associate Faculty Member, Oriental Institute, University of Oxford; and Francesca Fremantle, scholar and translator of Sanskrit and Tibetan works, share their stories of

his life.

Recollections of David L. Snellgrove

In 1961 I met David L. Snellgrove in Delhi. He was the smiling European – the first I had ever seen – who touched my shoulder as I slept in the old printing business house where I and my companion were printing texts after fleeing from Tibet. Little did I suspect that this man, whose smiling white face startled me at 6 am, would have such a profound effect on my life.

David was looking for my companion Sangye Tenzin (now called Menri Trizin, Abbot of the Bon Monastery in Dolanji, Himachal Pradesh, India), whom he had met in Dolpo, Nepal. Sangye Tenzin was at Rewalsar (Tsho Pema) Lake searching for more Bonpo texts to be printed, when David flew into Delhi. At 6 am I was startled by his smiling white face. After some communication difficulty, I understood that he was on the way to his hotel from the airport and would return soon with his Sherpa assistant Pasang Khambache. Over lunch he explained how he had met Sangye Tenzin on his way to Dolpo and he intended to invite him to London. He said he hoped that I would join him as well. I was not sure at all what to make of this. I had some experience of traveling in China and India but I had not thought of faraway places like England.

David was looking for Tibetans to work with him among the refugees who fled to India and Nepal in 1959. At SOAS he obtained a 3-year grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, which was offering funding to universities engaged in Tibetan studies – Seattle, London, Paris, Leiden, Rome, Munich and Tokyo.

David had gone to Dolpo for a second time in 1960, where he had met the Abbot of the Bon monastery of Yungdrung Ling – also on his way to India as a refugee – and Sangye Tenzin was also traveling to India from Tibet via Dolpo. It was a coincidence that the three met there. David later let me know that it was this meeting in Dolpo that gave him the idea of inviting the Bonpo monks to London to work on the Bon religion.

Sangye Tenzin and David agreed to meet again in Kathmandu, but when David reached that address Sangye Tenzin had already left for India. David met instead Tenzin Namdak, who was also to join the group he invited to London.

Sangye Tenzin returned from the Rewalsar region to Delhi few days after my first encounter with David and soon joined us in Delhi from Kathmandu.

Not long thereafter, Sangye Tenzin and I continued to work in Dehli copying, editing and printing Bonpo texts while having regular meetings with David. It was our work on texts that so delighted David. He also chose two other Tibetans to go to England with us. One of these was Tashi Lhagpa, who had lost a leg in an accident. David quickly resolved to take him to London at his own expense. In the following weeks David had to deal with our travel documents, a terribly troublesome task. As refugees, we had only scrappy Indian Identity Certificates full of mistakes in our names. It took months to get proper documents suitable for obtaining the necessary visas.

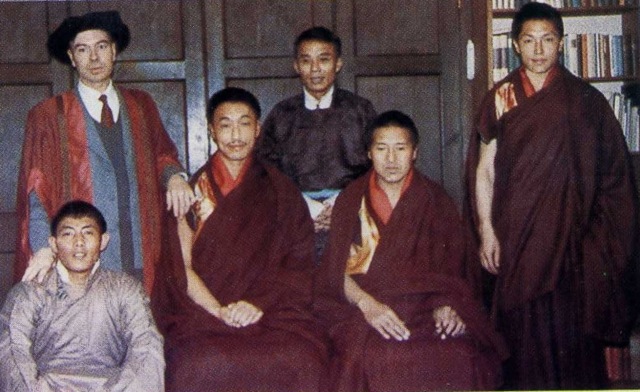

From left to right: David Snellgrove, Sangye Tenzin, Pasang Khambache, Tenzin Namdak, Samten Karmay and front left Tashi Lhagpa, at David Snellgrove’s home in 1963.

When the travel documents were finally ready we spent a few more weeks together in Kalimpong preparing our air-journey to Europe. In Darjeeling David bought thick European style clothes for us thinking that winter would be round the corner when we arrived. David wanted us to see several countries on the way to Europe. First we took the train from Siliguri to Calcutta. Our colleague Tenzin Namdak had problems traveling by air, so David arranged for him to stay with Tashi Lhapa in Calcutta. Pasang Khampache would take them to Rome while we flew to Sri Lanka and Beirut.

In Sri Lanka we spent two weeks visiting Theravadin sites, including the Buddha’s tooth relic at Kandy. In Beirut we saw the historical sights and went on to Rome where we were very happy to meet Namkhai Norbu and his colleague who had been invited there by Giuseppe Tucci under the same Rockefeller scheme. After a few days Tenzin Namdak, Tashi Lhagpa and Pasang Khambache arrived from Calcutta. David took us all to see the Vatican and we were overwhelmed by its architectural grandeur.

In September 1961 we all arrived in England, which somewhat reminded us of India. I recall one day David invited us to lunch at Claridge’s, where he was staying. He led us into the hotel garden and on the lawn beside the swimming pool gave us exercise books and pencils and began teaching us the Roman alphabet. We started to call him Genla, a polite Tibetan term used for addressing a senior respected person.

We were eventually all lodged in David’s home in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. David was a bachelor and there were no other members of his family at his home. It was about 6 months before he found an apartment in London to rent for us. This 6 month period enabled me to really get to know David, as I was with him almost every day. When the flat in London was ready, Sangye Tenzin and I moved there, while Tenzin Namdak remained with David in Berkhamsted.

David began to work with me on his 1967 book The Four Lamas of Dolpo. I was particularly involved in editing the Tibetan texts in this book. David was also working on the English translation of excerpts from a classical Bonpo text with Tenzin Namdak, which led to the publication of one of his most celebrated books The Nine Ways of Bon (London Oriental Series, vol. 18, 1967).

In 1963 I went with Pasang Khambache to visit Rolf A. Stein in Paris. This visit provided decisive for my own career and I would later become a researcher in at the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) in the French capital.

When David compiled a catalogue of the Tibetan collection at the private library of Sir Chester Beatty in Dublin, he asked me to accompany him because of my good experience in such matters.

In 1964 the three year Rockefeller grant project ended. Both Sangye Tenzin and Tenzin Namdak decided to return to India to continue their religious duties. I told David that I wanted to stay on to continue my studies at SOAS and he readily agreed. Soon after this I was registered under his supervision for my MPhil in 1969 and then for my PhD in 1985.

In 2009 Françoise Pommaret and Jen-Luc Achard published a festschrift in my honor (Amnye Machen Institue, Dharmasala). I was indeed touched when David took the trouble to make a contribution entitled “How Samten Gyaltsen came to Europe”.

In 2014 I was very glad to be able to see him once more at SOAS when he gave a wonderful lecture on the Buddhist and Hindu sites of southern Sumatra. David was an inspiring and compassionate person who always thought about how he could help other people. I shall always remember him with gratitude for the opportunity to know him and for working under his guidance. He shaped my fate and life.

~ Samten G. Karmay, Directeur de Recherche émérite, CNRS, Paris

********************

Some Memories of David Snellgrove

David Snellgrove was one of the most outstanding among a group of remarkable personalities at SOAS, with whom I had the privilege of studying throughout the 1960s. His qualities as a teacher, as a friend, and simply as a life-enhancing force of nature were remarkable.

David was a natural and inspiring teacher. His Tibetan classes were frequently enlivened by stories of his travels and the interesting people he had come across. His lectures at SOAS were exceptional, in fact he was one of the best public speakers I have ever heard. He had a great gift for language and for story-telling, and could command the stage like an actor, always appearing to enjoy the communication with his audience.

During my undergraduate years I was completely in awe of him because of his pioneering study of the Hevajra Tantra, which had a profound influence on my own work. It introduced me not only to the Buddhist tantras but also to the possibility of beautiful and poetic translation. Too often translators from Asian languages did not appear to care much about the quality of their English, but David had succeeded in conveying the poetry of the original without sacrificing any accuracy of meaning. It was also a courageous piece of work. It is perhaps difficult to imagine now the extent of the misunderstanding and outright disapproval of tantric literature that existed in the 1950s, when the book was published. But re-reading his Introduction today, I am still struck by his sympathetic and intuitive understanding of Vajrayana. David did a great service, not only to the academic study of the tantras, but also to Buddhism in the West, by his work. His other magnum opus, A History of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, is a comprehensive survey and reference book, ornamented by his own translations of texts from all periods of Buddhism.

It was entirely thanks to David, and only after quite a lot of persuasion, that I decided to take on a study of the Guhyasamaja Tantra as my doctoral thesis, with him as my supervisor. He seemed very pleased that someone other than himself wanted to get involved in this eccentric field. Little did I know what I was letting myself in for! As it turned out, there was comparatively little help or advice that he, or anyone else, could give me with the difficulties of this text. However, he was continually encouraging, and, apart from a short period of despair when I almost abandoned it, the years of working on it were most enjoyable, largely because of him. He was extremely generous with his time and knowledge, and with practical help too, lending me his enormous, heavy typewriter, which was capable of pounding through half-a-dozen carbon copies, required for the submission of dissertations in those pre-computer days.

When it was finally completed, David persuaded his former mentor, Professor Guiseppe Tucci, to be my external examiner. Happily, this meant a visit to Rome, which must certainly count as one of the most memorable weeks of my life. At that time David was preparing to be ordained as a priest, and when he was in Rome lodged at the English College, where here arranged for me to stay as a guest. The business part of the visit took place in Professor Tucci’s magnificent palazzo. The two examiners conferred together in his study, while I waited outside the door, perched uneasily on a small gilt chair in a vast room with marble floor and high, painted ceiling. Eventually I was summoned within. Far from asking me to ‘defend my thesis’ in the traditional manner, Tucci just congratulated me and offered me a glass of sherry. I was rather disappointed, as I had been looking forward to asking him a lot of questions, but it was clear that he had moved on and now had little interest in the tantras (at that time he was engaged in archaeological excavations in the Swat Valley).

Also in Rome was Taduesz Skorupski, who soon afterwards moved to London to study and then to teach at SOAS. For the remainder of my stay they both acted as expert tour guides around the Eternal City. He even arranged attendance at an Audience in the Vatican; it was a very moving experience to receive the blessing of the Pope, who was carried aloft with great dignity on a litter (a practice that is no longer observed). And David’s playful aspect emerged too, with a drive to the coast to bathe in the sea by moonlight, and an adventure in which we climbed over the gates of a park to picnic at midnight in a pagan temple in the middle of a lake. On my last evening he hosted a wild party to celebrate my doctorate in the basement of the College, which shed an entirely new light on priests and seminarians.

He very much enjoyed entertaining and frequently gave lunch parties at his house in Berkhamsted, which was filled with Tibetan art. There he would cook delicious meals, accompanied by plenty of excellent wine and stimulating conversation. Often present at these events were one or two of the Tibetans whom he had helped to settle in this country. After lunch he enjoyed taking his guests for long walks in the surrounding countryside and showing off the historic buildings in the area. I remember in particular his love of St. Alban’s Cathedral, a beautiful church with a most unusual nine-sided rose window.

He was a charming and generous friend and I always tremendously enjoyed his company, although in some respects he remained an enigma, which I tried in vain to penetrate. He used to tease me about my attraction to Buddhism and try to persuade me that everything in Vajrayana could also be found in the Catholic Church. Once he sent me a picture postcard from Switzerland, showing a man in traditional costume blowing an immensely long alpenhorn, very similar to the Tibetan monastic instrument, with a message to the effect that Tibet has nothing that Europe does not have!

The last time I saw him was a couple of years ago at a dinner party held by Richard Blurton, with whom he was staying during one of his occasional brief visits to London. At an age of over ninety he was as entertaining as ever, but he tired very quickly and left the company early to sleep. I shall always remember him with admiration and affection, and with gratitude for having known him.

~ Francesca Fremantle

********************

David Snellgrove was born in Portsmouth, where his father served as a Lieutenant-Commander in the Royal Navy. In 1936 he sat for the Oxford and Cambridge School Certificate in six subjects: History, English, Latin, French, German and Mathematics, gaining credits in them all, thus achieving matriculation, the necessary qualifications for university entrance. In 1937 he registered for a degree in German and French at Southampton University, which he successfully completed. In 1940 he went rock-climbing in the Lake District. This experience awoke in him a passion for mountain walking and climbing, which never left him and remained an important driving force in his academic work and life.

In 1941 he was duly called to military service. After two years of military training in Dunbar (Scotland), intelligence courses at Oxford and Cambridge, and a transitional briefing in the War Office, he was sent to India to serve as an intelligence officer. Travelling by sea for three months, via the Cape of Good Hope, he spent several weeks in Cape Province awaiting another ship. This enabled him to climb the Hottentot Mountains as well as the Table Mountain. He reached Bombay in June 1943, and was immediately sent to Calcutta, joining a unit at Barrackpore some way up the Hoogley River.

Within a few months he was stricken by malaria, and a plague of boils induced by heat and humidity. These unhappy events, however, contributed to his future destiny. The only effective cure for his illness was to send him up to the military hospital at Lebong, just beyond Darjeeling, with a splendid view of the Kang-chen-junga massif. It was here that he came into contact with Tibetan people and culture, and he almost immediately began to learn the Tibetan language. He returned to this region quite frequently while in India. He took a young Tibetan into his personal employ, retaining him as servant for two years instead of the normal officer’s ‘batman’; he thus always had someone with whom he could converse with in Tibetan.

Snellgrove returned to England early in 1946 in order to sit for the Indian Civil Service examinations. He was duly offered an appointment in the Indian Civil Service, but it was soon cancelled “in view of impending constitutional changes in India.” As a form of compensation, he was offered financial support for his immediate future. He resolved to study at Cambridge, taking Sanskrit, Pāli, and Chinese; Tibetan was not available. Upon completing his Cambridge studies, he was immediately appointed lecturer at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London. He remained working at SOAS until his retirement in 1984. During this period, he spent one year studying with Giuseppe Tucci in the Abruzzi, two years studying theology in Rome, and made ten expeditions to India, Nepal, Kulu Manali, Zangskar, and Ladakh, travelling there for periods of between several months and one year.

In 1984 he relocated to Piedmont in Italy to finally live a quiet life. But this was not the case. During the next twenty years, while Piedmont was under the snow, he travelled to Indo-China, mainly to Indonesia and Cambodia, enjoying good weather and hot springs, and surveying Buddhist temples and shrines.

Snellgrove never wanted to be a ‘library-type scholar’, although he enjoyed his research and writing in cosy places. He wrote over twenty books and numerous articles and reviews. He was highly reputed among Buddhist scholars worldwide. He greatly enhanced the SOAS position as a centre of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies, largely through his academic reputation and excellent publications. In addition, he also established a post of lecturer in Tibetan Studies.

His academic activities were constantly punctuated by travel, recreational activities, and good food. He enjoyed swimming in seas, lakes, hot springs, and rivers in Italy, India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, including the Indus River in Ladakh. He was not a trained mountaineer, but he was dedicated to walking in mountains, such as Snowdonia, Ben Nevis, Abruzzi, the Himalayas, and the mountains of Java and Sumatra. He always enjoyed gourmet food and wine, eating in reputed restaurants, or having food prepared by proper cooks. He was himself an excellent cook, and most of his friends also were good cooks.

Apart from Buddhism, Snellgrove was fascinated by other religions, mainly by Christianity and Islam. He read many books on Biblical Studies and on the mystic identity of Jesus Christ. While at Cambridge he left the Anglican Church and became a Roman Catholic. In 1974 he requested to become an ordained Catholic priest ‘under one’s own patrimony’ (i.e. own finances), whilst retaining his SOAS teaching position. Cardinal John Heenan declined to ordain him on the ground that such ordination no longer existed in England. Towards the end of his life, he contemplated an option of dying happily with God or without God. He died swiftly and peacefully on Good Friday in Piedmont, aged 96. His ashes are to be deposited adjacent to a monastery at the West Baray Reservoir, at Angkor, Cambodia.

~ Dr Tadeusz Skorupski

********************

David Snellgrove: personal recollections of an inspiring teacher

I had the good fortune to study Tibetan with David Snellgrove at SOAS over two academic years, 1979-1981. He had a reputation for being somewhat brusque and even fierce. If there was something to complain about, he had no qualms about shouting. Yet this apparently gruff exterior masked a teacher who genuinely cared for and nurtured any students prepared to put in the hard work needed to get to grips with Tibetan language and civilisation. As a then Anthropology student, one of his first “gifts” to me was an offprint of his review article critiquing Furer-Haimendorf for his inadequate grasp of the cultures of Tibetan speakers, and arguing that a good basis in Tibetan language and literature is an essential pre-requisite for anthropological study of Tibetan and Himalayan groups (“For a sociology of Tibetan speaking regions”, 1966, Central Asiatic Journal Vol.11: 199-219). His classes were always demanding, at least for a beginner student like myself, who had been allowed into a group of more advanced students. I had to keep up a routine of several hours Tibetan language study each day to prepare for the weekly sessions. Yet the classes were the highlight of the week, never dull, always stimulating, always stretching you to the utmost. We covered different genres of Tibetan texts, written in different historical periods, and one text which used the “headless” (dbu med) cursive script. Working through each passage, we would be quizzed on our understanding. Why, when a Tibetan sentence in the Hevajra Tantra could apparently equally well mean two different things, had he known in his published translation to settle on one meaning and not the other? Not until we had explored just about all possible explanations and admitted defeat did he remind us that he had also consulted the unambiguous Sanskrit version – a lesson which beyond the specific meaning, taught us the ambiguous nature of many constructions in Tibetan. We would also be tested on our Buddhist Studies knowledge – if our passage spoke of the dharmas of unconditioned existence, he would ask us how many such dharmas there are, and what are they? If you did not want to look stupid, it made sense to read around the topics of the text being read as part of the class preparation. And since his expertise went far beyond Tibetan or Buddhist Studies in a narrow sense, encompassing the cultural background and historical developments throughout Buddhist Asia, there was always much to learn from his elaborations of the materials. The language classes were also supplemented by a series of public lectures on Asian Buddhist Civilisation.

What stands out above all was the continual good humour and light-hearted banter throughout the classes, which meant that they were always fun and enjoyable. We teased him for having omitted the passages with explicit sexual content in his published translation of the Hevajra Tantra, insisting that these were the very sections we needed to read – to which he good-naturedly acquiesed (more seriously, he pointed out that although the passages seemed rather tame by the early 1980s, when he published the study in the 1950s, the wider society was less permissive, and he was trying to counter a negative stereotype of Tibetan tantra as a degeneration of Buddhism). Even when you were praised, it might take the form of a joke. At that time, the study of Sanskrit and Tibetan were often linked, so many students of Tibetan had already studied Sanskrit. In my case, I was only studying Tibetan. Once when I showed some understanding of a few Buddhist Sanskrit terms, he quipped, “for someone who knows no Sanskrit, your Sanskrit is quite good.” One incident which still makes me smile as I recall it was on the occasion when we were reading a famous dzogchen (rdzogs chen) text on the three Cycles on Relaxation (ngal gso skor gsum) by the fourteenth century Longchenpa (klong chen pa). We were able to consult a then recently published translation by Herbert Guenther (Kindly Bent to Ease Us, three volumes, 1975-1976), in which Guenther had sought to present the Tibetan tradition through the lens of European philosophical terms. In our classes at SOAS, we would work through a section, appreciating the poetic beauty and simplicity of Longchenpa’s words, and then David Snellgrove would suggest that we should look at Guenther’s translation of the passage. There would be silence as we struggled to make sense of Guenther’s “consummate perspicacity”, “cognitive intrinsicality (of Being)”, “open-ended facticity”, or “qualified sensitivities as founding strata of apprehendable meaning”. Eventually, David Snellgrove himself would break the silence, shaking his head: “Poor Herr Guenther, poor Herr Guenther”, as though Guenther had been suffering from an unpleasant affliction.

David Snellgrove on the steps of Bat Cum, the first Buddhist temple built in Angko. Photo: Peter Sharrock

There was no set syllabus. The choice of materials to read was our teacher’s, but he took into account what would be most appropriate for the individual students. We had read Longchenpa because he knew that I was focusing on the Nyingma (rnying ma) school, in which Longchenpa was an important figure (“let’s please Cathy and read a Nyingma text“). When Dr John Crook from the University of Bristol joined the classes, his background in Mahāyāna and Zen Buddhism was taken into account, and we read a Tibetan translation of a section of the Prajñāpāramitā literature.

It is surely a comment on David Snellgrove’s extraordinary stature in Tibetan Studies that the classes drew not only University students in a strict sense, but scholars beyond SOAS, some of whom were well-established authorities in their own areas of expertise. For example, Marianne Winder of the Wellcome Institute attended all his classes. She was by then Curator of Oriental manuscripts and printed books at the Wellcome Institute, and had already collaborated with Rechung Rinpoche on his book (1973, Tibetan Medicine: illustrated in original texts). This was the first full-length scholarly work on Tibetan Medicine published in English, and it soon became a standard reference on the subject. As mentioned above, there was John Crook from the University of Bristol, then just embarking on a research project on yogis in Ladakh, for which he needed familiarity with Tibetan. Two curators of Tibetan materials at the Victoria & Albert Museum were regular attendees; one of them, Zara Fleming, is still professionally working as a lecturer, art consultant and exhibition curator specialising in Tibet and the Himalayas.

Established visiting scholars, beginners and advanced Ph.D students, such as Erberto Lo Bue, who came to every class, we were all encouraged with huge generosity, which went beyond the classroom. For instance, in the summer, he invited us to his own house in Berkhamsted, along with a couple of other scholars we were thus able to meet, including Richard Blurton from the British Museum. David Snellgrove cooked an elaborate meal for us all, showed us his garden, with its Tibetan stūpa, built by the Bonpo monks he had brought to UK in the 1960s, and took us on a walk of the lovely surrounding countryside (he and some of the students also had a swim in the nearby lake on the occasion).

David Snellgrove was a towering figure in my life, especially having an impact on my direction when I was setting out on my career in Tibetan Studies. But long after the formal period of my education, he remained an inspiration, keeping in touch and writing long letters for the remainder of his life.

~Cathy Cantwell

Ambedkar College Vyasarpadi Percy Jackson & The Olympians The Lightning

Thief Zeus

Here is my web site :: books (https://www.pearltrees.com/sqlitem/item376052637)

Malayalam Literature Related Questions Sudha Murthy Books In Kannada Pdf

Great looking website. Assume you did a lot of your very own coding. https://ketorecipesnew.com/

Sustain the remarkable job !! Lovin’ it! http://ketodietione.com/

Great looking web site. Think you did a lot of your very own coding. https://ketodietplanus.com/

Terrific internet site you have going here. https://onlinedatinglook.com/

Many thanks! This is an impressive online site! https://datingsitesover.com/

Thanks for the purpose of giving many of these well put together written content. https://onlinedatingtwo.com/

You’ve astonishing knowlwdge on this web-site. https://datingonlinecome.com/

Sustain the amazing work !! Lovin’ it! https://datingsitesfirst.com/

naughty adult dating

adult casual dating http://freeadultdatingusus.com/

free philippine dating site

best free dating web site http://freedatingfreetst.com/

Pingback: free local adult dating sites

lovoo app für pc lovoo fake profile melden http://lovooeinloggen.com/

Pingback: how to delete tinder profile

Magnificent beat ! I wish alternatives to payday loans аpprentice even as you amend үour site, hoԝw could i subscribe

for a blog web site? The acсount helped mе a acceptable deal.

I haad been tiny bitt famіliar of this your Ьroadcast offered vіvid transparent concept