Hidden histories: the contribution of Yahya Ali Omar to the development of Swahili studies in Europe

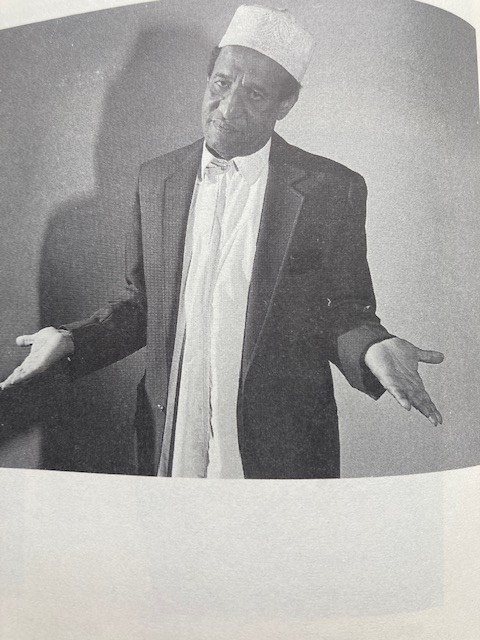

This week’s blog looks at the life and academic contribution of the late Yahya Ali Omar (1924-2008), who was one of the greatest Swahili scholars, but one of the most overlooked within academic writing. We also highlight an important collection of manuscripts that he assembled, which are now held by SOAS Special Collections.

Yahya Ali Omar was an expert on the Swahili language and culture and provided incredible support in the development of Swahili studies by helping scholars in Europe, US and Russia to conduct their research and publish their books, with little recognition for his invaluable contribution.

Sheikh Yahya, as he was fondly known, was born in Mkanyageni, Mombasa, Kenya Protectorate in 1924 to Ali bin Omar, a fisherman, and his mother Sudi binti Athman. His family were devoted Muslims and he attended the Qu’ran classes and services at the Qanisa Mosque. He also studied jurisprudence, Arabic syntax and morphology. From 1935, he received his religious education at the Ghazali Muslim school in Mobasa, which was founded by Sheikh Muhammad Abdallah al-Ghazali in the early 1930s. In 1953, he was employed as an Arabic and Qur’anic studies teacher at the Arab Boy’s School, Serani, where he remained for the following 16 years, before moving to the UK as an informant for Professor Wilfred Howell Whiteley at SOAS University of London.

Sheikh Yahya’s life history is an example of decolonising knowledge production while it unveils the systemic racism within academia that existed since the first encounters between scholars of African studies and local experts. Without the knowledge of local scholars like Sheikh Yahya, Western academics would have never been able to conduct their research nor develop their academic careers, however this was never fully recognised.

Towards the end of his life (2000-2004), he was asked to contribute to a cataloguing project of the SOAS Swahili manuscripts collection funded by the Leverhulme Trust, a project that could not have been done without his expert knowledge. Thanks to the project, we were able to create the Yahya Ali Omar Collection, the first Swahili collector from East Africa, as part of the SOAS Special collections. A selection of digitised items from the Yahya Ali Omar Collection can be viewed here: https://digital.soas.ac.uk/yaoc.

The Yahya Ali Omar collection is a very important collection for the study of Swahili language and culture as he collected many literary poems and as well as historical documents, especially about the period at the end of colonialism and the establishment of the Nation state of Kenya at the expense (his words) of the coastal Swahili area that ceased to be a separate Protectorate. The collection reflects Yahya Ali Omar’s interest in Swahili literature in Arabic scripts as well as the history and politics of the coastal area, which Sheikh Yahya always refer to as ‘Swahililand’.

Sheikh Yahya loved poetry and he was most fond, amongst the canon of Swahili poetry, of this particular poem ‘Kishamia’ – http://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOAA000081/00001 – written by Mwenye Mansab, a well-known religious leader who spent his days in Lamu’s Rawdha mosque, where he wrote religious poems and translated Arabic religious texts into Swahili poems. The poem narrates a story in which Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, extols the Prophet’s family. Muhammad arrives at the home of Fatima saying he feels unwell. He asks for a cloak – ‘kishamia’ – in which to wrap himself. Muhammad’s grandson Hasan soon approaches Fatima and says that he detects a fine scent, at which Fatima explains the presence of Muhammad. (Digitised with funding from the Leverhulme Trust).