Wishing you a very Happy New Year- Nianhua [年畫]

This week’s blog comes from Jiyeon Wood, Subject Librarian for Arts & Multi-Media, and celebrates the Chinese New Year through SOAS Library’s fascinating collection of Chinese woodblock prints.

Are you familiar with the lunar calendar? In Korea, where I’m from, the lunar calendar is still used. For example, my parents’ birthdays are set by the lunar calendar, which means that they celebrate their birthdays on a different day every year – you can probably imagine the problems. Moreover, although January 1st is still a public holiday, the proper New Year [설날, Sŏllal] is celebrated at a time dictated by the Lunar calendar (sometime between 21st of January and 20th February) with 3 days of public holiday. This year the Lunar New Year will be on Friday 16th February. It celebrates the start of the Year of the Dog.

Although the Lunar New Year is celebrated in many Asian countries such as Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia, it is often referred to as the ‘Chinese New Year’. This is probably because it was first celebrated in China during the Shang Dynasty (1766 BC-1122 BC).

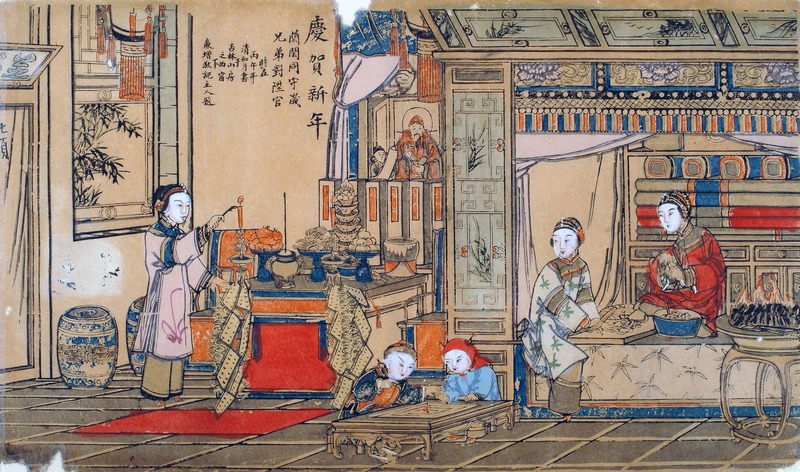

The Chinese New Year is often a theme on Chinese woodblock prints, a collection of which is held in the Library at SOAS. A single-sheet of a Chinese woodblock print is often known as nianhua [年畫], which means literally New-Year picture. The Library has over a hundred popular Chinese woodblock prints, predominantly from the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is worth noting that some of our prints were designed and engraved in the highly regarded specialised print shops of Yangliuqing [楊柳青] in Tianjin, Taohuawu [桃花塢] in Suzhou and Yangjiabu [楊家埠] in Shandong. The coloured print below shows “Qinghe xinnian tu” [慶賀新年圖, Celebrating the New Year festival] from Yangliuqing print shops. The print illustrates a domestic scene on the eve of the New Year: lighting alter candles, making dumplings and children playing games.

慶賀新年圖 CWP 59 http://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOAA003987/00001 © SOAS

Woodblock printing thrived from as early as the ninth century in China until the end of the Qing dynasty, and prints were often used to create or reproduce a wide array of graphic narratives, religious icons and social themes that were destined for mass consumption through the annual New Year markets[i]. New-Year prints were displayed on the doors and walls of ordinary people’s houses. Some had a protective function. Some were for the happiness and wealth of the family. Some were calendars or just decorative.

福 CWP 78 http://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOAA004010/00001 © SOAS

As in the example above, the images of the Celestial Officials dressed in imperial robes symbolise good fortune and official promotion. The character ‘fu’ [福] on their shoulders means good fortune, wishing that the home owner may receive both wealth and the blessing of good fortune. These prints were often produced in pairs that faced one another. They were pasted on each side on the door or gate of the home or business to keep evil spirits from entering.

武門神 CWP 4-b https://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOAA003938/00001 © SOAS

Some prints depict military officials with weapons or fearsome protective demon-quellers, known as the door gods [門 神]. The origin of the door god custom goes back to the Tang Dynasty. The emperor Taizong (太宗, r. 627-650) fell sick and suffered from nightmares of ghosts harassing him. His two loyal generals Qin Shubao and Yichi Jingde stayed the night to keep watch over the emperor. After a good night’s sleep, the Emperor recovered from the illness and had their portraits posted up in his palace. In later years many other figures were used as door gods, often portrayed with red faces.

The New Year pictures also portray common themes such as Kitchen gods and the Spring Ox Calendar. Kitchen god prints were traditionally placed on the kitchen wall to prevent fire. The Spring Ox Calendar is a single sheet pictorial almanac illustrating events associated with Spring ploughing ceremony. In the Spring Ox Calendar [春牛圖], you will always find images of the Spring Ox [春牛] and its herd boy (or sometimes known as the spirit driver) Mang shen [芒神]. The colour of ox and the clothes of Mang shen were denoted according to the interpretations of almanac and other references of that year. “If the ox was painted yellow, the summer would be hot; if green, there would be sickness in spring; if red, there would be drought; if black, there would be much rain; and if white, there would be high winds and storms[ii]” If Mang shen wore a hat and no shoes, the year would be dry; if no hat and shoes, there would be rain; heavy clothes signalled great heat; light dress would indicate cold weather etc[iii]. In the Library, we have 4 Spring Ox Calendars (CWP 6, CWP 7, CWP 8 & CWP 44).

Among them, the oldest almanac is this Spring Ox calendar (CWP 44) from Suzhou, dated 1843 with the title Yangguo Jinbao Chunniu tu [洋國進寶春牛圖, Foreign countries presenting treasures]. Woodblock prints at this time were influenced by Western engravings and this print is a fine example of European influence in terms of colours and technique.

洋國進寶春牛圖CWP 44 http://digital.soas.ac.uk/LOAA003971/00001 © SOAS

This print is a rare because the Suzhou print industry was destroyed by the Taiping forces in 1861[iv]. It is interesting to note that the title of the print is ironic as 1843 was when China was defeated by the British during the Opium War. China believed that riches would flow by opening ports to foreign trade but, in contrast, China ended up importing opium in return for silver.

Some people think the term “Nianhua (New Year’s prints)” is misleading as it is too narrow a term to describe the full range of subjects and purpose of the prints, especially since old and worn out prints were replaced at different times throughout the year.[v] Nevertheless, it is a name which has stuck.

SOAS Library has an excellent range of prints depicting historical events such as Taiping Rebellion [CWP31-a/b], The Boxer Rebellion [CWP22] and the Sino-Japanese war [CWP11]. Some prints describes popular fiction and plays such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms [CWP33] and Journey to the West [CWP57]. In the SOAS Digital Library, you can explore Chinese Woodblock prints which are not found in any other UK collection.

Why don’t you take a look and pick some images to protect and decorate your home this year?

Wishing you a Happy Lunar (Chinese) New Year.

Chinese Woodblock prints can be consulted in the Special Collections Reading Room. For the list, please check “Preliminary list of Chinese woodblock prints in the SOAS Library.” Requests should be made in advance to Archives & Special Collections at special.collections@soas.ac.uk

[i] Flath, J.A.2011. Social Narratives in Yangliuqing “Nianhua” of the 1930s’, Arts Asiatiques, p. 69, JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost, viewed 18 January 2018.

[ii] Flath, J.A.2004. The Cult of Happiness: Ninhua, Art, and History in Rural North China. Vancouver: UBC Press.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Laing, E.J.2004.Selling Happiness; calendar posters and visual culture in Early-Twentieth-Century Shanghai. Honolulu: Univesrity of Huwai’I press.

[v] Ibid.