The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: ‘Afterlife’

The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: exploring missionary archives has been running at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, over the past 6 months, and has just closed its doors to the public. This blog series highlights some of the fascinating stories and archives selected for the exhibition from the collections at SOAS Library.

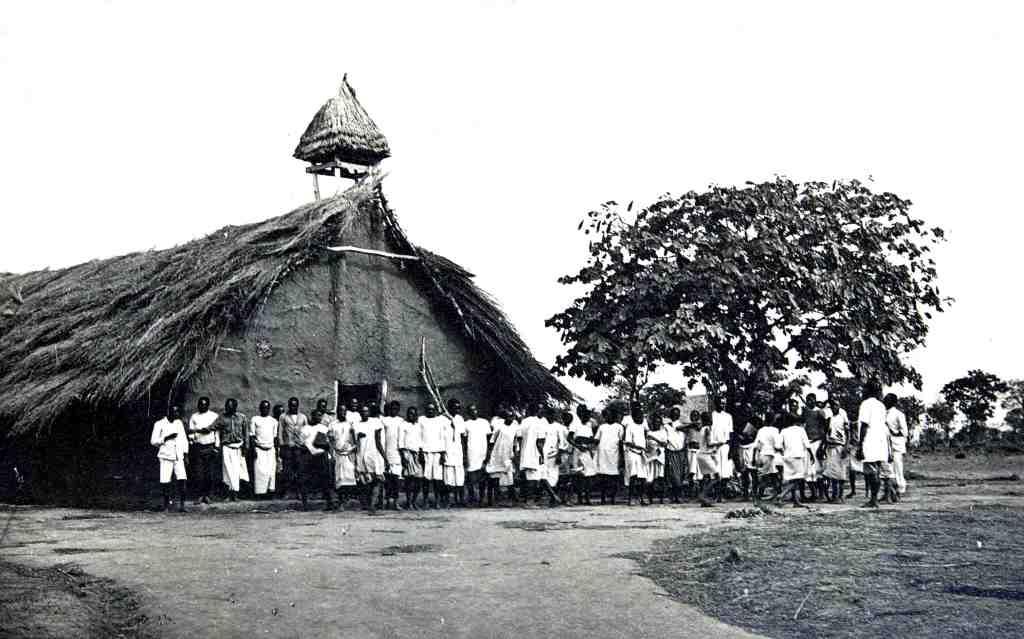

The history of how Livingstone’s life has been remembered and reinterpreted is a complex and changing one. Initially missionaries had the greatest incentive to keep his memory alive as a means of furthering European Christianity, using him to help with recruitment and fund-raising. The London Missionary Society (LMS) was intensely interested in ‘memorialising’ Livingstone after his death in 1873. Its approach was reverent and uncritical, and he came to embody heroism and self-sacrifice as well as devotion to duty and to Christ. The Society promoted Livingstone’s memory at missionary exhibitions and through publications generated by its own publishing arm, the Livingstone Press. For the centenary of his birth in 1913, it organised a series of high-profile public events.

Meanwhile, Livingstone became one of imperialism’s foremost heroes – reflected in contemporary biographies. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he was seen to be a forerunner of the imperial ‘scramble’ who ushered in a new era for Africa. But as the empire changed, Livingstone’s image adapted too. Following the First World War and the establishment of the League of Nations, some biographers suggested that he had pioneered the new imperial creed of international ‘trusteeship’. As the empire declined, Livingstone continued to be reinvented. In the 1950s, when imperialism was supposedly dead, he was hailed as the spiritual forefather of ‘partnership’ and collaboration between the races.

Under colonial rule, place names appeared such as Livingstone in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), and Blantyre in Nyasaland (Malawi). White settlers chose to remember Livingstone as a great pioneer and the father of British liberal rule – a tradition of which they claimed to be part.

After independence Livingstone continued to be remembered in some African countries. The first president of Zambia, Dr Kenneth Kaunda, himself mission-educated, attended celebrations to mark the 100th anniversary of Livingstone’s death in 1973, describing him as “Africa’s first freedom fighter”. Others see him in a much less favourable light, namely as the symbol of British Imperialism in Africa and the direct inspiration for the European exploitation of the continent which followed in the years after his death.