The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: Map-making

The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: exploring missionary archives is running at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, until 17 May 2014. This blog series highlights some of the fascinating stories and archives selected for the exhibition from the collections at SOAS Library.

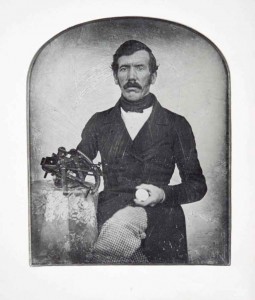

Daguerrotype of David Livingstone holding the sextant and pocket watch used to make calculations © Council for World Mission

Livingstone’s maps, reports and published narratives of his travels gave the world their first view of the interior of south-central Africa and changed people’s perceptions of that continent. By looking closely at original maps and letters, we can learn something of his mapping techniques, including how heavily Livingstone relied on the knowledge of the indigenous peoples.

During his earliest expeditions, Livingstone was not in a position to explore the entire Zambezi River system himself and often questioned the local people for information, incorporating these details into his reports and maps. He expresses the methodology by which many of the maps were drawn up in a letter to the editor of The Athenaeum in 1856:

“We travel in the company of men who are well acquainted with parts of the country by personal observation… They soon see that we are interested in the courses of rivers, names of hills, tribes…and make enquiries among the villagers to whom we come. Drawings are made on the ground and parts pointed out that bearings may be taken and comparisons drawn from the views of different individuals. We thus gain a general idea of the whole country. We confess our obligations to native information, we admit our liability to mistake. It is discovery not a survey.” (Livingstone to Editor of the Athenaeum, 25 Nov 1856. Royal Geographical Society Archives, ref: DL 2/12)

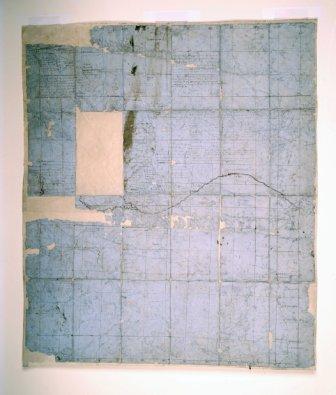

Livingstone’s original manuscript sketch map of the Zambezi River drainage area has an interesting history. On its completion in 1851, Livingstone sent it by messengers to his father-in-law, Robert Moffat, requesting that it be forwarded to the Society’s directors in London. Moffat had the map copied by his son Robert. Livingstone later presented the original map to the Rev William Thompson, agent of the London Missionary Society (LMS), who in turn left it to his son, the Rev Ralph Wardlaw Thompson, Foreign Secretary of the LMS from 1880 to 1914. Wardlaw Thompson had the map displayed in Livingstone House, the Headquarters of the Society, in London. During World War II, German bombs destroyed Livingstone House. The remains of the map were recovered from the ruins and the fragments carefully pieced together. As is evident, it was seriously damaged and sections were missing. In November 1955 this partially reconstructed map was presented on permanent loan to the acting Prime Minister of the then Federation of the Rhodesias and Nyasaland, Sir Roy Welensky. After the Federation was dissolved in 1964, the map was returned to London where it is now kept in the archives at SOAS on permanent loan from the Council for World Mission.