The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: Livingstone the doctor

The Life and Afterlife of David Livingstone: exploring missionary archives is running at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS, until 17 May 2014. This blog series highlights some of the fascinating stories and archives selected for the exhibition from the collections at SOAS Library.

Watercolour painting of "Dr Livingstone's Medicine Chest used by him on his last journey”, 1940 © Council for World Mission

David Livingstone was one of the first medical missionaries to enter Southern Africa. He was a skilled physician-surgeon, whose medical expertise and reputation was also the means by which he gained the trust of local chiefs as he negotiated his way through their territories. At a time when many of his contemporaries dismissed the approaches adopted by local healers, Livingstone remained practical – recording and testing traditional plant and mineral-based remedies alongside whatever western medicines he was able to procure.

Livingstone’s letters and published narratives are full of his observations of the diseases he encountered in Africa, and their impact on both Europeans and Africans. These included malaria, cholera, dysentery, leprosy, river blindness, tuberculosis, typhoid, tropical “eating” ulcers and “sleeping sickness”.

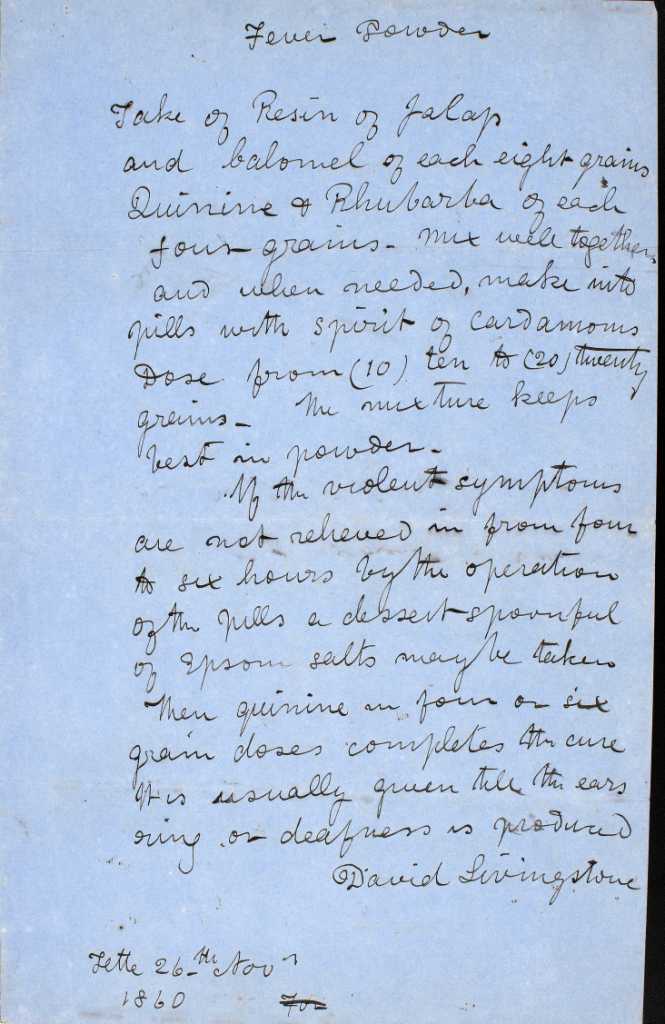

Malaria was seen as the single biggest obstacle to European settlement and trade in Africa. At that time, it was thought that the disease was caused by ‘miasma’ or bad air. Livingstone suffered repeated attacks, as did his children and his wife, Mary, who died from malaria in 1862. Although he was never to know the actual cause of the disease, Livingstone observed that it seemed more prevalent where mosquitoes flourished, and he adopted the Arab custom of using mosquito nets at night. He also developed his own cure, becoming one of the first to administer quinine in a dose that was effective enough to keep the death rate on his expeditions comparatively low.

Livingstone’s treatment for ‘fever’ included both purgatives and diuretic, which encouraged bowel movements to express black bile from the gall bladder. Side effects included mental confusion, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting; and the sign of a cure was temporary deafness or ringing in the ears (tinnitus), caused by an overdose of quinine. In his published account of the Zambezi Expedition, Livingstone adds, “They received from our men the name of “rousers” from their efficacy in rousing up even the most prostrated.” The fever recipe was later manufactured in tablet form by the chemists Burroughs-Wellcome right up until the 1920s, under the name ‘Livingstone’s Rousers’.